It is the central paradox of the Klitschko brothers in the United States that so many fans declare so frequently their disdain for the style in which the brothers fight, yet every time a Klitschko appears on HBO of late he does respectable to excellent ratings. Or maybe it’s not a pardox at all. Maybe there are just two kinds of fans: those who discuss boxing in the public sphere (on blogs like this one, on message boards, on Twitter) and don’t like Wladimir and Vitali, and a different group that is off quietly enjoying the two-headed kings of the heavyweight division.

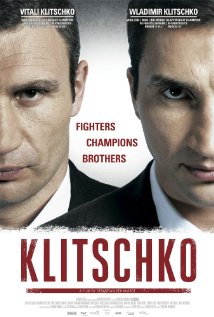

That is the one major unexamined phenomenon in the documentary “Klitschko,” a 2011 German film airing Sept. 8 on HBO in advance of Vitali’s latest fight and a fight with its own stylistic detractors, Andre Ward-Chad Dawson. The dearth of heavyweight competition, Vitali’s political career, whether the siblings will fight each other, whether they have the requisite toughness expected of boxers… most every aspect of the things people say about the Klitschkos is given at least lip service. All of it ends up at “flattering.” But then, why would a German documentary about German (by way of Ukraine) heroes examine a question that is moot there? Whether the Klitschkos fight in a boring style is irrelevant in Germany, because the pair are viewed very differently in Deutchland, where the standards of what constitutes boxing entertainment is different than here. The Klitschkos are lionized there, so a documentary from Germany wouldn’t even think to examine such a narrow, U.S. perspective.

Flattering though it may be, “Klitschko” — a review copy of which was provided to TQBR by HBO — is not without its value. It’s not as if there aren’t flattering things to say about the Klitschkos that are true: They’re good at punching people, the best of this era of heavyweights by far, such as it is. They are devoted to charity work and improving their home country. And while they’ve always shown bursts of likable personalities in the short interviews or video clips in which they most frequently appear in the United States, “Klitschko” gives them just short of two hours to stretch their legs. They are funny and insightfully reflective.

Perhaps that’s part of their appeal in America, too, for those who watch them in silence. The personality of athletes can draw or repel fans. Sometimes, repellent personalities, like that of Floyd Mayweather, draw fans, too. But the Klitschkos have a marketing hook or two aside from their personalities, like the dabbling in politics, their enormous size, Wladimir’s famous ex-girlfriend (OK, Hayden Panettiere is another commonly discussed Klitschko topic left out of the documentary) and the fact that they are brothers.

The greatest strength of “Klitschko” lies in its illumination of the relationship between the brothers, and how they differ. Their upbringing is gripping material, particularly their father’s role in cleaning up the Chernobyl disaster. That military connection swiftly swings from darkly comical (Vitali as a rascally youth once brought home a landmine) to serio-comic (After equipment involved in the Chernobyl clean-up was returned to the Klitschkos’ neighborhood and washed off, Wladimir would play in the radioactive puddles – perhaps that explains their enormous size?) to tragic (Wladimir’s father watched many friends die from radiation exposure, and, as Vitali recounts it, the doctor who diagnosed their father’s cancer said, “In the end, Chernobyl got him, too”).

Vitali has a protective impulse about his younger brother that is endearing, even if Wladimir is annoyed by it; Vitali, after Wlad’s loss to Lamon Brewster, tried to get his sibling to quit boxing, and watching Vitali go nuts in the corner during Wladimir-Samuel Peter is a good bit of showing, rather than telling. Despite their differences on that matter – Wladimir dislikes negativity like criticism while Vitali feeds off it – the brothers are close.

There are other differences besides, and the differences in their personalities inform their identities as boxers. Perhaps the best bit of insight from the film features an old coach comparing Vitali to stone and Wladimir to clay. Vitali is nearly indestructible, but it’s harder to change him as a result, whereas Wladimir is easier to mould but quicker to weather. We also see how Vitali is more impulsive and instinctive, and Wladimir is more studious and precise. In this, the thoughtful, eloquent self-awareness of the brothers is another asset to the film, because their telling accents the showing. “He was born a fighter,” Wladimir says of Vitali. “I became one.”

From there, the film offers a mostly honest and engaging recounting of the Klitschko brothers’ boxing careers, from their arrival from Soviet-era Russia in America (Vitali offers, “How can there be 100 different types of cheeses? It’s madness. There’s one kind of cheese. It’s called cheese,” in a moment a New York Times critic suggested might have been rehearsed) to a Don King seduction gone awry (King reveals his character while pretending to play a piano he can’t, prompting the brothers to move along) to slow motion fight footage that is lovely and a selection of fights discussed that is a fairly accurate accounting of the story arcs of the brothers in the ring. Vitali’s shoulder injury against Chris Byrd and Wladimir’s losses to Corrie Sanders and Lamon Brewster are given a predominantly proper treatment, and since those stories have redemptive happy endings, then so do they in the film.

There are three Klitschko career blemishes that in two cases get ignored by the filmmakers and in another case benefit from incomplete history. Vitali, by his own admission, used to take steroids, a not insignificant controversy in Vitali’s career arc and one that the filmmakers almost appear to ignore deliberately. Wladimir’s gold medal Olympic run gets a mention, but there is only a vague mention of a “ban” that Vitali received – is that the same ban that got him kicked off the Ukranian Olympic team for using steroids, perhaps? And if you’re going to discuss what went wrong for Wladimir in the Brewster fight, why not mention his crackpot theory that the Brewster camp poisoned him before the fight? And if you’re going to raise the issue of Brewster’s blindness in one eye and blame it on a Robert Helenius fight in 2010, why not mention that Brewster fought a Wladimir rematch after surgery on a detached retina, with an eye that had been in bad shape even before that – and, by the way, in the rematch, Brewster looked like shit, raising questions about whether he was dangerously cashing out his unhealthy remaining boxing life? Perhaps time constraints factors into it, but when so much else of “Klitschko” comes out unremittingly positive, a little bit of scrutiny that doesn’t end with a happy rainbow might also have been nice.

I have other small complaints – there is some corny editing here and there, like silly overdubbed “FLOOM” and “BOOSH” sound effects on slow motion punches, or ridiculous guitar music, or Mike Tyson’s gleaming tooth in a still photo; it also takes until near the end of the film before anyone suggests there’s anything contradictory about repeatedly calling the Klitschkos “the heavyweight champions,” plural – but “Klitschko” is a boxing documentary I can recommend. There are moments that legitimately shine, separate from the film’s artificially friendly light. You might know mainly good things about the Klitschko brothers afterward, but you’ll nonetheless know things worth knowing about these unique, towering figures on the boxing landscape.