So continues our marathon coverage of one of the biggest fights of 2012, Manny Pacquiao vs. Timothy Bradley on June 9 on HBO pay-per-view. Previously: the stakes of Pacquiao-Bradley; getting to know Bradley; the undercard, previewed; keys to the fight, part I; the Rabbit Punch column takes on Pacquiao-Bradley. Next: a final preview and prediction.

Mind. Matter. How do Manny Pacquiao and Timothy Bradley stack up in those categories? In the second of two parts, we compare their more mental attributes.

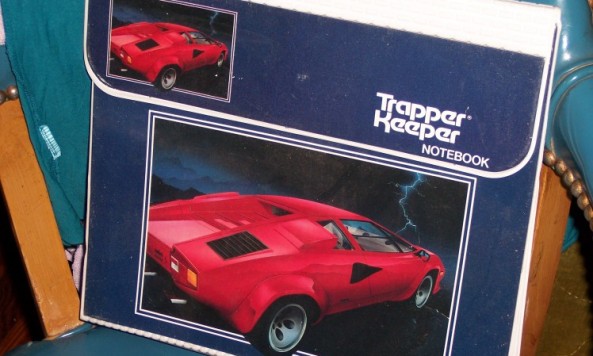

(The [Trapper]Ke{y}[eper]s to the fight.)

Offense. Bradley’s offense is a weird mixture of intelligent pressure and simply flinging things at his opponent — he doesn’t care which hand makes contact, he doesn’t care where it lands, he doesn’t care whether he’s inside or outside and he doesn’t even care if it’s his head doing the hitting. His best punch is is overhand right, and he can lead with it, throw it in a combo or use it as a counter after pulling back from his opponent’s missed shot. His counter left is usually pretty sharp, too. Mainly he just lets them fly. He wants to dig to the body but takes what his man gives him. There’s a pawing jab in there, and the occasional uppercut. Sometimes he throws sloppy and wide, sometimes short and accurate. His overall desire to make contact of any kind means he misses plenty, but he throws enough punches that usually one blow in a sequence lands. It all can be a bit messy, but the messiness often works to his advantage by keeping his man off guard, and I get the impression that it’s all by design, not the result of any lack of know-how. He has things he’d rather do — like being on the inside, although he was strangely effective against the taller Lamont Peterson on the outside — but he’s a versatile boxer for someone who depends on a handful of punches and appears disorganized at times.

Conditions are ripe for some firefights, because Pacquiao himself attacks in bursts, like Bradley. He isn’t as volume-oriented, as he’s more interested in making meaningful contact than Bradley’s anything-will-do. And once he dials in on an opponent, he usually stays locked in; only the clever Juan Manuel Marquez in recent fights has been able to move periodically off Pacquiao’s grid. The speed and two-handed approach from odd angles are a big part of the overall attack, but he’ll also throw change-ups and use his jab to find range. He’s more comfortable countering than ever, although he prefers to lead, and he can launch his offense from the inside or the outside, although he would rather get in and out or sidestep before resetting. And, of course, the straight left remains deadly for this all-time great southpaw. Bradley has an effective offense, but Pacquiao’s is more focused, more damaging with his big power and has a better combination of awkwardness mixed with technical proficiency. Edge: Pacquiao

Defense. Almost exclusively, Bradley ducks punches. This has the advantage of getting him into head butting position — and yes, I’m convinced he does it on purpose — because he’ll duck a shot and then pop his head up toward his opponent, often firing with one hand or the other. It could make him vulnerable to uppercuts, but no one has exploited that tendency yet. He doesn’t catch much on his gloves, although he keeps his arms low on the inside to defend against body punches. And he will occasionally step to the side to avoid return fire after his own volley. It’s mainly ducking, and if he’s on the outside, it’s more upper body movement, where he’ll pull back to protect his head. His sloppiness on offense is where he gets most in trouble; he can be caught very, very flush with punches while trying to fire his own, his head dangling in tantalizing fashion. He also has, in some fights, squared his body up and made himself an easy target.

There was a stretch there where Pacquiao was a defensive dynamo, where his legs were so springy and his gloves were always in such perfect position, but those days are gone. Maybe the weird calf problems he’s had have something to do with that. Maybe it’s because he’s gone back to a macho give-and-take. Maybe his reflexes have slowed. Against Marquez, he was doing some Bradleyesque ducking out of harm that was somewhat effective. Of his stretch of opponents since settling in at welterweight — Marquez, Shane Mosley, Antonio Margarito, Joshua Clottey, Miguel Cotto — only Mosley has had substantial trouble making contact. Both men are capable of good defense, but both are unreliable practitioners. One has been more consistent than the other. Edge: Bradley

Intelligence. I always feel like I’m saying Pacquiao is dumb when I talk about this category, but I’m not. He’s clearly been an excellent learner, and he’s had one of the great teachers in trainer Freddie Roach. In between fights, he is quite intelligent, as he’s also very good at picking up Roach’s battle plans and implementing them. Where he isn’t as brainy as some fighters is, he just doesn’t make adjustments within fights. If something is going poorly for Pacquiao, it will stay going poorly unless his opponent’s stamina tails off or he abandons what was working for him. Roach will often tell him what he’s screwing up, but Pacquiao either doesn’t listen or can’t fix things on the fly. There’s a knock on Roach here, too, for this particular fight: He keeps comparing Bradley to Ricky Hatton. Hatton is an underrated fighter, in my view, but Bradley is a more complex one, by far. Bradley might deploy pressure and body punching like Hatton, but the similarities end there. If Roach is planning for Hatton, then he will be coming up with the wrong plan for Bradley.

This category is one where Bradley is very dangerous for Pacquiao. If he gets into any trouble whatsoever, Bradley squirts out of it. He can win in any number of ways. I go back to the Peterson fight: The plan for Bradley, against a taller opponent, had to have been to get on the inside. But once it became clear Peterson was just as comfortable if more comfortable there than Bradley, Bradley stepped back and fought off his back foot. His trainer, Joel Diaz, has worked with some other good fighters, the best of them junior featherweight Abner Mares, but is no longer with Mares. Bradley’s his main horse, and they’ve both profited from it. Diaz and Bradley are saying the right things about Pacquiao, unlike Roach and Pacquiao in reverse: Bradley needs to be a moving target who gives Pacquiao angles, something that worked for Mosley on defense, and Bradley needs to stay disciplined rather than freelancing in the event that he encounters success. Bradley’s ability to make adjustments, and his team’s more accurate pronouncements about his opponent, are the difference. Edge: Bradley

Willpower. Confidence is no problem for Bradley. His self-belief is quite clearly enormous, and it’s been a huge weapon for him in the ring. In every single fight he’s been in, he has simply wanted it more than the other man. Nor does strife perturb him. If he goes down, it doesn’t bother him much. If he gets cut, he acts like it never happened. If anything, his manic desire to win might drag him down back around the other side: He’s been training so long for this fight (and is a notorious hard worker while training) that he might have overtrained and drained his body.

Pacquiao is a great competitor himself, but there are more holes in his makeup than Bradley’s. One is that he hates being cut. He will be operating at anywhere from 25 to 75 percent capacity with a particularly bad one, at least until it gets patched up. This is telling, because there’s a really strong chance that Bradley will cut Pacquiao with a head butt at some point. Another shortcoming is that Pacquiao gets distracted easily during training camp, and while he sometimes feeds off the distractions, he also sometimes has blamed them for lackluster performances. The latest wrinkle in this phenomenon is that he has become very, very religious since his last fight, and apparently had to be convinced that boxing was something God could endorse. How bad is Pacquiao going to want it with doubts like that creeping into his head? Especially since he has been contemplating retirement for a long time now? That’s more questions than are wise to have against someone with Bradley’s determination. Edge: Bradley

The Rest. Bradley isn’t used to fighting on a big stage like this, with the closest he’s come being on a Pacquiao undercard, and while I doubt it will affect him much, Pacquiao will be the more comfortable of the two… Pacquiao also will have all the fans in his corner. I’m no even sure Bradley has fans, although that hasn’t affected his performances in the past — he probably hasn’t had people rooting against him before, however…. If it’s close on the scorecards, Pacquaio is usually going to get the star treatment. One of the judges, though, Jerry Roth, did score the second Marquez fight for Marquez, while another, Duane Ford, scored it for Pacquiao… Bradley’s the rule bender of the two, especially with the head butting. It’ll be an advantage for him. It’s not clear if referee Robert Byrd is equipped to handle Bradley’s tactics as he hasn’t reffed a fight this big in the past, but to his credit, there are very few negatives out there about Byrd… For what reasons might the fight stop early? A Bradley disqualification, but probably not; someone knocking out the other guy, and Pacquiao is clearly the better finisher of the two; a cut, one that would probably be on Pacquiao rather than Bradley, or an injury, perhaps to Pacquiao’s legs that make it so he can’t go anymore. Edge: Pacquiao