Cinephiles and film buffs have, especially in recent years, lamented the retelling and rehashing of old stories — especially the “grasping at straws” attempts to inject new life into a tale that seemed to be concisely summed up the first time.

In “An Evening With Kevin Smith,” the director related an anecdote about being approached to write a script for a “Beetlejuice” sequel called “Beetlejuice Goes Hawaiian.” He went on to say, “Didn’t we say all we needed to say with the first ‘Beetlejuice?’ Must we go tropical?”

Mr. Smith has a point, and it would seem that there are only so many ways to tell one story. Yet so many legends and myths and parables are but altered versions of an original.

In boxing, likely the most common tale is a lowly fighter from squalid beginnings slithering his way through the greedy reptiles, past contention and into the grip of a championship belt. And money. The reality is far more grim for your average pugilist, but the fantasy does a carrot dangle that pushes men to sacrifice all for a mere glimpse.

Leon and Michael Spinks took turns both affirming stereotypes, and swatting them away with stacks of cash.

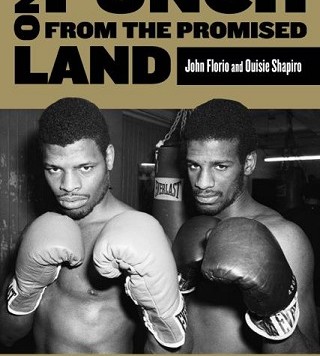

At 248 pages (full disclosure: an advanced copy given to review), John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro take a research- and interview-based approach to chronicling the adrenaline-soaked highs, and the cold, muddy lows in “One Punch From The Promised Land.” And like so many of the happenings in boxing, truth far outweighs fiction when assessing strangeness and amusement.

What seem to be a slower first few sections and chapters should be familiar to fans of nonfiction, as Florio and Shapiro deftly prepare the reader to understand the Spinks brothers in context, polishing a proper lens through which to view them. Scraping through life and living in a housing project in north St. Louis, Mo. called Pruitt-Igoe would have been a risky proposition for an adult in the late 1960’s, never mind seven children and a single mother in one small apartment.

As boxer James Caldwell related in an interview, “Some guy would walk up to a car and start shooting. We’d all scatter. As soon as the commotion was over, we’d go back out and start playing ball again.”

In true, fantastical boxing fashion, Leon and Michael Spinks bashed their way out of clutches of north St. Louis, and into the comforting, patriotic shimmer of Olympic gold medals in 1976.

Though the ending to the Spinks story isn’t a mystery to many a boxing fan, the details have now been spilled on pages in a way that allows a milestone-by-milestone and sin-by-sin reliving. Through the ascent to the fistic glory of both Leon and Michael winning lineal championships, earning millions and becoming household names, Florio and Shapiro dish out constant reminders of where both men came from, and how the past nipped at their heels at every turn.

Michael Spinks, the more soft-spoken of the two, has a compelling story in his own right, though it lacks the gritty heroic tragedy of Leon’s. The authors relay firsthand accounts and interviews that illustrate just how Leon appeared to abandon sanity as Michael forged his own future, initially intent on getting into boxing to look after his blood.

In an interview with the late Emanuel Steward, the trainer said of a newly-anointed heavyweight champion Leon, “He moved across the street from where I live in Detroit. …[Leon] gets a beautiful house in a neighborhood called Rosedale Park, and a friend of mine invites me to go there for a party. I open up the door, it was just, to say it was off the hook is an understatement. They were doing some kind of train, everybody’s going through the whole house. Leon had his cowboy hat on, and a couple of guys are yelling, ‘C’mon Coach, get on!’ So I get on with ’em. I see a football player from Pittsburgh, and he’s got a game the next day. It was unbelievable. That was the first time I got to see Leon personally. The whole house was rocking. When he would have parties, everybody’s house on the block would be moving. You’d call him and tell him to turn the music down. [He’d ask,] ‘Is it loud?'”

A likely intended analogy in the book, the Spinks brother lived their lives outside the ring just as they did inside of it: Leon tossed haymakers at existence, not worried about whether he would gas out later on, while Michael was far more careful and calculated in his approach. As Leon plowed through women and pyramids of cocaine, Michael generally preferred to save his money — sometimes to the point of being labeled “cheap” — but was willing to help out their mother Kay with bills when she needed it. Michael wasn’t completely straight laced or square, however, as he was named Exemplary Boxer of the Year for his “impeccable conduct in and out of the ring” by the World Boxing Council in 1983, despite being fined for carrying an unregistered handgun in Philadelphia a few months prior.

Nonetheless, a bond of blood couldn’t deter the Spinks brothers from traveling down clearly divergent paths at some point.

It’s not wholly clear in “One Punch From The Promised Land” whether or not Leon was chewed up and spat out by boxing, but he certainly rode it as a means to a hungover, strung out end. From heavyweight champion to makeshift handyman, Leon Spinks was rarely without his trademark infectious smile, sometimes with front teeth included, but usually without.

Michael Spinks, with all his planning and saving, appeared to be destined for a different fate — a smarter fate. He made good money, invested, worked hard, and retired from boxing without much of a rear view mirror. He was repaid for his frugality the only way boxing knows how to offer remuneration: upon the passing of his good friend and manager Butch Lewis in 2011, Michael would come to find that most of his fortune had been spent by the flamboyant character.

The lone knock on the book would probably be that it was very difficult to keep up with some of the names and characters, some of which hadn’t been involved in the story for chapters at a time, it seemed. Interviews break up what may otherwise be monotony, however, and Leon’s story in particular tugs the narrative forward.

The bottom of the cover reads, “Leon Spinks, Michael Spinks, And The Myth Of The Heavyweight Title,” and Florio and Shapiro thematically sew the delicacies and hard truths of being not only a heavyweight champion, but a black heavyweight champion, straight through the eye holes of the narrative. From Jack Johnson to Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali to Larry Holmes, and eventually Mike Tyson, the definition of “black heavyweight champion” is given a slightly different look, but through the eyes of brothers this time.

Butch Lewis said in a previous interview with Sports Illustrated, as quoted in the book, “People would come up to [Michael] and make fun of Leon. Everybody would have a Leon Spinks joke. [Michael] would want to punch those people in the mouth. He was confused. He wasn’t sure if that’s what happened when you became heavyweight champion or if Leon was bringing it on himself.”

At the last heartbeat, either the heavyweight championship was indeed a myth, or Leon and Michael Spinks were but men caught in its path.