So continues our marathon coverage of one of the biggest fights of 2011, Floyd Mayweather vs. Victor Ortiz on Sept. 17 on HBO pay-per-view. Previously: the stakes of Mayweather-Ortiz. Next: keys to the fight.

Dearest casual boxing fan or non-boxing fan: The Victor Ortiz you’ve met is not the Victor Ortiz we hardcore fans all know. It’s not that you’ve been lied to about the would-be conqueror of Floyd Mayweather, exactly. Much of what you’ve seen from HBO’s 24/7 Mayweather/Ortiz or the interview with Piers Morgan is true, or as true as anything gets about Ortiz. And I don’t mean to pull rank. But you’ve only had so much experience with him, and I want to help shed light. For those who have watched his every fight and read his every interview from the time when he was one of boxing’s blue chip prospects until he arrived at his somewhat ambiguous status now, there are many different feelings about Vic.

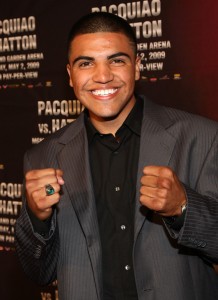

He is a figure who largely plays the “face” — to borrow the pro wrestling term for hero — a fighter who is catnip for televised boxing ratings and a popular ticket seller; he is also a figure who is loathed as a “heel” by a good many boxing fans who think he’s a total phony. He has a gorgeous smile, but it hides a lot of pain, some of which you’ve become acquainted with because his painful family history and his rise above it has been visited by the aforementioned programs, but some of which has been glossed over because little attention has been paid to the perception among boxing fans that he lacks a certain machismo and is a fighter whose accomplishments are worthy only of scorn, despite all his considerable speed and power.

In what I just wrote, I might as well have described Oscar De La Hoya. In short, Victor is as close to Oscar as any fighter today: someone viewed on the outside of the sport one way, on the inside another. Early on, Ortiz was hyped as the “next Golden Boy,” cribbing De La Hoya’s nickname, and Ortiz has actively taken after his promoter — but few could’ve anticipated all the ways, good and bad, they would parallel one another. As if to deliberately rack up the similarities, the same week that De La Hoya admitted it was him in those infamous fishnet photos, Ortiz debuted a side gig as an underwear model.

This account comes, by the way, from someone who basically views Ortiz positively. I enjoy his fights. I appreciate his good qualities.

But he’s a mess of contradictions. It’s the kind of thing you might expect, really, from a 24-year-old still discovering himself after a rough personal history and a professional career that crashed to the ground at the moment where it most prominently entered the spotlight.

I’m not going to belabor the point about Ortiz’ personal history. The tale of his mother and father leaving him to raise his brother by himself has already been told and is already being told well elsewhere, to the extent that some regular boxing fans are already sick of hearing about it. But it’s part of the explanation about how a young man nicknamed “Vicious” could also take the approach of trying so hard to be nice that people don’t believe it’s real (and maybe it’s not all real), who possesses an air of being such a naif even though his job is knocking other people out.

Setting aside his back story, it’s how he has behaved in the ring and what he says when he talks that leads to some of Ortiz’ reputation problems.

Ortiz had been cruising through the junior welterweight division when he ran into Marcos Maidana in his first headlining fight on HBO in 2009. It was an exciting contest: Both men spilled all over the canvas in a toe-to-toe slugfest. But eventually, it was the gritty Argentinian whose intestinal fortitude surpassed Ortiz’, and when a ring doctor was examining Ortiz’ swollen eye, he waved so as to indicate that he was quitting the fight.

That was strike one. For most hardcore boxing fans, there is no crime more severe than for a boxer to quit. It’s a warrior culture, even for those who aren’t the warriors themselves. In boxing, you aren’t supposed to give up, ever.

Strike two came moments later. Ironically, given the views these days that he is a fake, it was his candor about how he felt about that moment at the end of the fight that cost him so much of his reputation. He admitted in a post-fight interview in blunt terms that he did give up, and that he didn’t know if he would ever be cut out for such punishment.

De La Hoya has had his warrior spirit questioned many times before, as it happens, including after one fight in which he was accused of quitting against Bernard Hopkins.

Before the Maidana fight, there were already suspicions about whether Ortiz’ persona as a good, genuine guy was legitimate. But since that fight, he’s spoken any number of totally laughable falsehoods that threw his sincerity into doubt, because the alternative was that he might be out of his gourd. He’s also alternated between unconvincing tough guy talk and remarks seemingly designed to make him seem neat-o, the way De La Hoya used to do. (If the broader populace noticed this tendency of De La Hoya’s, it might have kept them from loving him so much — but many long-time admirers of the sweet science got used to rolling their eyes in disgust at De La Hoya’s pronouncements.)

Ortiz talked tough about how Maidana was scared of a rematch and was hiding from him, a ridiculous notion that Maidana denied directly but that didn’t make any sense on its face; why would Maidana make Ortiz quit, then be afraid to fight him again? More recently, he’s been claiming he wanted to fight Mayweather since he was nine years old, but every aspect of that story rings untrue. He’s also retained elements of his good guy self. My view is that sometimes, his golly-gee-whiz talk is authentic, the product of a friendly Midwesterner melding with surfer culture, as he has become an avid surfer. And I don’t think anyone with his background affiliates himself with a program like Big Brothers Big Sisters and is insincere about it. But some of the golly-gee-whiz stuff? It feels like he’s playing to the crowd, and that he’s not a very good actor.

Meanwhile, as his personality became loathed by large swaths of boxing fandom, he went about rebuilding himself in the ring. He became less inclined to stand and trade blows, deepening suspicions that he lacked guts, even though everyone pretty much agreed that he had the ability to more intelligently against Maidana and could have defeated him by NOT standing toe-to-toe. His competition was weak, which is what happens when a fighter is rebuilding from a loss, but it was at times very, very weak and he still got HBO dates that few thought were deserved, given the poor match-ups. It made him yet more disliked.

Some of this made Ortiz appear surly and withdrawn, at times. In some interviews, he refused to discuss Maidana, asked about it as he is over and over again. He seemingly bristles at the view of HBO’s Max Kellerman, whose interview following the Maidana fight prompted the remarks he might never live down. In a recent conference call with the media, he spent a large portion of the conversation haranguing reporters. But this being Ortiz, even all of that has been a subject of speculation about his true feelings; perhaps, some of us thought, he was just trying to hype himself up, to give himself the motivation of thinking that the world was against him.

At long last, when he finally got a chance to prove he had heart, he did it. In his defeat of Andre Berto, his welterweight debut in the spring, he hit the canvas and never quit; he took punishment and never backed down. He redeemed himself, to a degree. But even though Berto was the betting favorite in the fight, Berto is a figure of even greater disdain than Ortiz. He is flat-out hated by a great many boxing fans, and his in-ring accomplishments have been serially downgraded by same. So while the win was good enough to get Ortiz a #2 ranking in the division from Ring Magazine, it wasn’t the kind of win that restored him to some of his early esteem. Here is where some of the De La Hoya comparisons are limited; despite his string of losses against all-time greats, De La Hoya was once briefly viewed as the best fighter in the world, and Ortiz hasn’t sniffed at that kind of achievement. And some rightly wanted to see a pattern of heart from Ortiz, not a one-time showing. After all, De La Hoya got accused of lacking heart when he spent the late rounds of his fight with Felix Trinidad circling away, only to gut out a war against Fernando Vargas, only later to be accused of quitting against B-Hop and giving away a potential win by taking his foot off the gas against… wait for it… Mayweather.

That brings this all full circle. I’ve said a lot about how Ortiz is viewed by hardcore boxing fans. For me, it comes down to this: Ortiz doesn’t know who he is yet, either as a man or as a boxer. He’s a 24-year-old. Did you know who you were when you were 24, really? And did you have to spend some of your key developmental years dealing with any of the family strife Ortiz did, or was every element of your character thrown into question by hundreds of thousands of people in full public view for a couple years? I don’t know if all of those conditions will ever allow Ortiz to become a genuine person, rather than someone who acts like he’s shuffling through personas as though he’s trying them on for size or using them for whatever he’s trying to do at the time. Maybe he’ll genuinely become a person who’s permanently phony. It’s not as if anyone is convinced these days that De La Hoya is being “real” all the time. I don’t know where Ortiz is going. I just don’t think that he’s arrived there.

If Ortiz loses Saturday, he’ll be in good company. Everyone who fights Mayweather loses to him, so far. We might learn something about how he rebounds from an even higher-profile loss on an even bigger stage. But if Ortiz doesn’t beat Mayweather, he’ll merely be doing what’s expected of him. We might not learn much about him at all, unless he loses in a distinctly Ortizian way that somehow confirms the negative view of Vic.

But if Ortiz topples the great Mayweather, absent Mayweather losing in some peculiar method (like an injury, or him suddenly looking “shot”)? I think we’ll see Ortiz in a very, very different light. It would be a light that — because he would be doing something his mentor De La Hoya couldn’t do — would dispel some of the shadow cast by the man he mimics, sometimes intentionally and sometimes not, sometimes for good and sometimes for ill.