If you think boxing has become a crazy, convoluted, beautiful mess only in the last 25 years, Hank Schwartz has a story to tell you.

When Don King was only a year or two out of a prison cell and Oscar De La Hoya hadn’t taken his first breath, Brooklyn-born telecommunications executive Schwartz arguably was the biggest mover and shaker in boxing. His company, Video Techniques, handled the nascent technology of satellite transmission of major fights to televisions and closed-circuit theaters around the world and also distributed and promoted the biggest bouts from one of the golden eras of the heavyweight division, 1971-75.

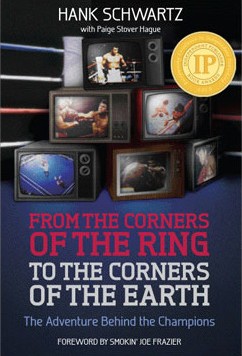

Schwartz tells his incredible story in his new book, “From the Corners of the Ring to the Corners of the Earth.” There’s very little that’s ordinary about the tales in this book, which sometimes pushes the adage “truth is stranger than fiction” to the edges of belief.

By 1971, Schwartz’s company, Video Techniques, had focused on the distribution of sporting and political events through microwave satellite technology. And his expertise in that field couldn’t have come at a better time since heavyweight championship bouts started to take place in far-flung corners of the world such as Kingston, Jamaica, Caracas, Venezuela, Kinshasa, Zaire, Tokyo and Manila, where microwave and satellite technology was vital to beam the fights to screens across the planet.

Schwartz also quickly discovered that he could make even more money by serving in a dual role as the promoter of these big fights around the globe, offering the fighters and the broadcast technology and infrastructure in one-stop shopping to dictators and despots desperate to show their strife- or poverty-filled nations as good citizens of the world.

He also had a key ally in his rocket ride to the top of the boxing world in the early 70s: Muhammad Ali. Schwartz developed a business relationship and friendship with Ali and his entourage, including business manager Gene Kilroy, when he handled the television production of The Greatest’s fight against Mac Foster in Tokyo in 1972.

That relationship evolved into promotion and technical coordination of bouts between George Foreman and Joe Frazier in Jamaica, Foreman and Joe Roman in Tokyo, Foreman and Ken Norton in Caracas, the legendary “Rumble in the Jungle” between Ali and Foreman in Zaire and arguably the greatest heavyweight fight of all time, the completion of the Ali-Frazier trilogy in the “Thrilla in Manila.”

That lineup should get any boxing fan salivating for details like one of Pavlov’s dogs looking at a raw sirloin. But Schwartz is a storyteller much like a guy you see every Saturday night regaling buddies over a frosty mug of Pabst Blue Ribbon at your corner bar, not a writer.

And that’s one of the agonies and ecstasies of this book: Schwartz tells some incredible stories that are almost beyond belief, especially when dealing with the military-led governments of some of the nations where he staged fights. There also are gems such as the time Bob Arum passed out from smoking a cigar-sized joint in Jamaica and when a minister was executed on the spot during a meeting that Schwartz attended in Zaire, leading Schwartz to be named as his successor.

But there’s so little detail about boxing, as in-ring accounts of most of the fights that Schwartz promoted are covered in a couple of pages or less. Maybe that was by design, as Schwartz realized that everyone knew the outcome of these classic bouts. Plus he was in the production facility for these fights.

Still, Schwartz became close to many of the lords of the sport during this golden era. Yet he never really gives the reader a look into what made these men international supernovas except for a few funny, revealing anecdotes about Foreman, who was one, moody, eccentric cat those days, a far cry from the grinning, grill-slinging everyman we know today.

“From the Corners of the Ring to the Corners of the Earth” is a collection of “Can you f*cking believe this?” stories from an incredible period of four or five years during the fascinating life of an interesting guy. There’s no shame in that. But by the time the book reached the “Rumble in the Jungle,” the tales of Schwartz’s adventures almost become a rote equation with new names and places.

The Schwartz fight production flash cards used to write this book could be summarized as: Add Massive Problem A into Banana Republic B run by Corrupt Dictator C, multiply by Major, Last-Minute Sh*tstorm D solved by Workaround or Brilliant Idea E to put on a great fight. More details about the production or the fight preparation could have provided more depth.

But again, this book is more of a barroom conversation than the analysis or reporting you get from a pure boxing writer like Thomas Hauser or Hugh McIlvanney.

And this book is saved from tedium in the final chapters when the great underlying current of the Schwartz story swirls into a mighty wind: the rise of Don King.

Once Schwartz decided to go into the boxing promotion business, he needed a conduit to the fighters. Once King stretched his tentacles past the boxing halls of Cleveland, he needed a conduit to the great fight stages of the world.

It was the ultimate boxing marriage of convenience, and it worked for a while. But King’s icy ambition and syrupy charm quickly mixed into a Machiavellian cocktail that Schwartz couldn’t spit out.

Thankfully, Schwartz does go into detail about his work with King and how King worked around the fringes of the boxing system to rise to power. He also gives a clear window into King’s fascinating mix of street smarts and back-stabbing hustle, while offering tacit acknowledgment of King’s intelligence.

I don’t think Schwartz was the bumbling, cautious businessman depicted by Jeremy Piven in the television movie, “Don King: Only in America,” constantly under the thumb of the connivingly superior King. Schwartz was one smart cookie to promote and handle the technical details of these fights. And that only serves to reinforce King’s genius, as he still was able to outmaneuver Schwartz and essentially put Video Techniques out of the boxing business by 1980.

Schwartz tried to intimate that he was done with boxing at that time because Ali’s career also was over, but that was a sliver of ego hiding the truth: Don King buried him.

It’s a bit of a sad tale, because it’s pretty safe to say that Hank Schwartz made Don King from 1971-75. Together they made some of the greatest fights of the 20th century.

And despite the lack of depth in the details and the barroom nature of the story telling, that’s the overarching beauty of this book: Big fights among the greatest fighters were made at exotic locations all around the world despite huge promotional and technical obstacles, keeping a bout for the heavyweight championship of the world as THE marquee sporting event that could stop the metronome of daily life whenever it happened. Schwartz and King were the driving forces behind that phenomenon for a short time.

It’s a far cry from today, when financial pissing matches between men with enough money to line city sewer systems prevent many global megabouts from happening, even with the add-water-for-a-gourmet meal built-in infrastructure of Las Vegas.

Can you imagine Bob Arum or Oscar De La Hoya putting on the Floyd Mayweather-Manny Pacquiao fight in Zaire, Manila or Caracas, all while trying to successfully use technology that was undeveloped in those nations? Neither can I. But I can’t imagine them putting on a fight of that magnitude, period.

But Hank Schwartz did many times, and he has given us an epic travelogue of his wild ride. And that is more than reason enough to read “From the Corners of the Ring to the Corners of the Earth.” It’s a magical era and story that sadly never will be repeated in boxing.