Kelly Pavlik played the starring role in the most thrilling fight I have ever attended in person, his 2007 middleweight championship fight against Jermain Taylor in which he rose from the canvas and scored a stunning knockout to claim the lineal title at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City.

(Not only was the fight poster cool as the Fonz, it was prescient, too.)

The fight was so good that, despite the fact that I had a financial interest in Taylor’s victory (hey, the Champ at the time was barely a favorite and was seconds from victory in the second round; I defend that bet to this day), I left Boardwalk Hall with a huge smile plastered on my face. Money comes and goes, but I had witnessed an event that I knew would be branded into my memory forever.

For this reason, I am particularly ashamed of my harsh treatment of Pavlik in the last year-plus, when he rapidly descended in my opinion from, “guy I will watch fight anywhere, against anyone,” to, “guy who needs to fight Paul Williams before I lose all interest in him and his stupid staph-infected hands.” In fairness, I had a lot of company on the Pavlik-doubter bandwagon, which formed after his decisive decision loss to Bernard Hopkins and grew fervent with his inability to fight due to hand injuries and his perceived disinterest in fighting anyone with a pulse when he wasn’t hurt.

As I prepare to take another trip down to Boardwalk Hall to see Pavlik in what amounts, more or less, to another pick ‘em fight for the middleweight championship against Sergio Martinez, I feel compelled to revisit Pavlik’s career via BoxRec, my favorite time-wasting site in the world (next to TQBR, of course).

The Rise Of The Ghost

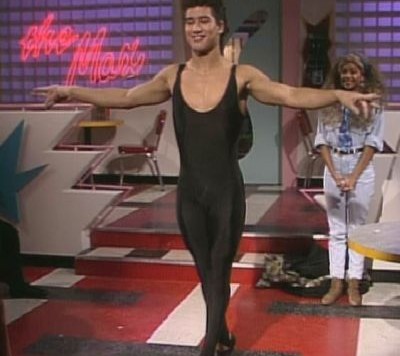

Pavlik started his career slowly, accumulating 26 wins without a loss with nary a notable name on his resume. Unless, of course, you count Mario Lopez as a notable name. Given that the man who once gave breath to A.C. Slater on Saved By The Bell has served as a part of the broadcast team for several smaller pay-per-views (and maybe some Versus shows or something? My memory is chemically debilitated…), I actually checked whether Lopez the boxer and Lopez the actor were one in the same. Alas, they are not, though they were born only six months apart in 1973.

(Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, dance like A.C. Slater)

Too bad, or I could have started calling Pavlik’s straight right hand the Zack Attack.

The first true test of Pavlik’s career came when he faced Fulgencio Zuniga, a strong Colombian with knockout power who boasted a 17-1-1 record going into the fight with Pavlik. Pavlik and Zuniga engaged in an entertaining brawl, as Zuniga dropped Pavlik early but Pavlik responded with the strong knockout victory to announce himself as a serious prospect on the verge of being a contender.

After testing himself against a fellow prospect, Pavlik set his sights on established veteran contender Bronco McKart, another lesson in Fighter Development 101 (step 1, build the record; step 2, beat other prospectes; step 3, measure up against an experienced contender). McKart, a former WBO light middleweight titlist who fought one of the most unheralded trilogies of all time against Winky Wright (losing by SD, UD, and DQ), became the second fighter in a row to drop Pavlik. Pavlik again responded like a warrior and eventually stopped McKart in the sixth round. McKart was still a real threat, going on to split a pair of fights with contender Enrique Ornales and fighting to a draw with Raul Marquez, as Pavlik moved on to bigger and better things.

Guts And Glory

Pavlik continued his upward trajectory by retiring journeyman Lenord Pierre (most notable for being among the astounding 276 losses in the career of Reggie Strickland, who is guaranteed a future Bowels of BoxRec feature), then made his move to the big time. HBO gave him the opportunity to fight against Jose Luis Zertuche on the network, with the winner likely to face the winner of the Edison Miranda-Allan Green bout to fight for the right to face middleweight champion Jermain Taylor.

Zertuche, a tough hombre who had nonetheless lost a tight split decision to former Pavlik victim Zuniga in his previous fight, helped boost Pavlik’s reputation as an action fighter, as the two thrilled the HBO audience before Pavlik’s crushing power came through again, stopping Zertuche in the eighth round. Meanwhile, Miranda earned a unanimous decision over Green in which Green put forth a bizarre performance, seemingly entranced by his shoelaces.

This set up the biggest fight of Pavlik’s young career, a fight that cemented him as a possible star of the future and a fighter that HBO deemed worthy of a strong push, his battle with Edison Miranda. Miranda had defeated Green, a highly touted prospect at the time (honestly, he’s not much more than that now), and nearly took Willie Gibbs’ head off in his fight before that. The only blemish on Miranda’s record going into the Pavlik fight was a highly controversial decision loss in Germany, when he broke Arthur Abraham’s jaw yet received a whopping total of 5 points deducted from his score in losing a disputed yet clear-cut unanimous decision.

The iron will that would prove to be Pavlik’s salvation in his greatest moment was on display from the outset in the Miranda fight. While other boxers fought tentatively against the wild-swinging Colombian (Gibbs looked like he would have rather been boxing a kangaroo), Pavlik stalked his powerful foe from the outset, out-machismo-ing a man whose greatest strength was arguably his machismo. He imposed his will, took control of the ring, and embodied scores of other clichés in authoring a rousing and decisive TKO win about a minute into the seventh round.

With dominant wins over Zertuche and Miranda fresh in the minds of HBO boxing fans, Pavlik was ordained the next challenger to Jermain Taylor’s middleweight crown. Taylor was in the midst of a fan backlash against his championship run, receiving criticism for facing smaller opponents after his two close decision wins over Bernard Hopkins. The bout was highly anticipated nonetheless, pitting two young, unbeaten American middleweights together in front of a rabid partisan Pavlik crowd.

The fight was thrilling from the outset, as Pavlik tried to use his jab, size, and strength as Taylor worked to outbox his bigger foe. Early on, Taylor’s athleticism and skill earned him an advantage, and he floored Pavlik in the second round with a blazing combination punctuated by a dynamite right hand. The challenger took the count and rose on unsteady legs. Taylor pounced (though perhaps not aggressively enough), but Pavlik regained his legs and showed his tremendous resolve to survive the round.

After that, momentum swung. Taylor had thrown his best shots at his opponent and Pavlik kept on coming on, undaunted. Pavlik’s confidence grew while Taylor’s waned. Taylor continued to land hard shots and control portions of the fight, but Pavlik’s power was wearing down the champ like erosion in fast-forward. In the seventh, a hard right hand sent Taylor reeling to the corner. Pavlik reigned a hailstorm of blows on the dazed Taylor, prompting referee Steve Smoger to jump in and stop the bout to the elation of the crowd.

Seven fights earlier, Pavlik had knocked out sub-.500 Vincent Harris. On this day, he became middleweight champion of the world.

To date, that moment stands as the pinnacle of his career.

Catch As Catch Can

After winning the middleweight championship, fans hoped Kelly Pavlik would satisfy their demands for intriguing fights more than Taylor had. First, however, Pavlik had to dispatch of the former champ again, as Taylor had activated his rematch clause. The second fight, at a 164-pound catchweight, produced far fewer fireworks and highlight reel moments than the first. Pavlik earned a clear unanimous decision victory, though the bout inspired ominous speculation that Pavlik’s power might not go up in weight with him.

For his first title defense, Pavlik squared off against Gary Lockett, who boasted a solid 30-1 record but had few notable wins on his record (Ryan Rhodes is the only name I recognize). Many fans and pundits criticized Pavlik’s choice in opponent but, given his increasingly difficult strength of schedule over his previous two years, he was more or less given a pass for taking on a soft foe.

Pavlik disposed of Lockett in the third round. Lockett has not fought since.

Unfortunately for Pavlik, the middleweight division did not exactly boast a long roster of deserving challengers. Arthur Abraham stood out as a potential dream foe but neither side seemed to push seriously to make the fight. Lacking in strong challengers, Pavlik looked outside his division and found his opponent, the man who had owned the middleweight championship for a decade.

Bernard Hopkins, 43 years old at the time, had already begun to establish himself as one of the greatest over-40 fighters in history after losing his middleweight championship to Taylor. He rose in weight to dominate Antonio Tarver for the light heavyweight championship, then lost a razor-thin split decision to Joe Calzaghe that many (including me) though he deserved to win.

Tarver and Calzaghe, however, were older fighters, and many considered Hopkins to be on the “senior circuit” until he signed to fight Pavlik. However, Hopkins would prove to have several advantages over his young, strong foe, including style, experience, and – perhaps most importantly – size. Hopkins would not be fighting Pavlik for his old middleweight crown; instead, the fight was signed for a 170 pound catchweight, the second catchweight fight for Pavlik after winning the middleweight title.

While Pavlik has proven himself a devastating middleweight, his success outside the division is far less convincing. At middleweight, he stopped Jermain Taylor emphatically. At 164 pounds, he beat him by clear but competitive decision. At 170 pounds, he was taken to school by Hopkins, losing nearly every round.

Hopkins’ dominant performance prompted the first backlash against Pavlik. Fans contended he couldn’t fight above middleweight. Pundits wondered whether he could deal with slick boxers. Dismissive critics emerged and labeled him a basic 1-2 fighter. Pavlik shook off the loss as a product of sickness the night of the bout, and prepared for his second middleweight title defense, against Marco Antonio Rubio.

In many ways, Rubio was the poster boy for the lackluster middleweight division. He had some decent wins on his resume (Zertuche, Enrique Ornales) but was nothing more than an average contender who posed little threat to the champ. Rubio retired before coming out for the tenth round, having not won a round on any of the three scorecards, yet some fans were still dissatisfied.

At least, until this point, Pavlik was fighting regularly. After beating Rubio, Pavlik would be out of the ring for nearly ten months, and the biggest wave of backlash would seemingly wash away so much of Pavlik’s promise and hard work.

I Wanna Hold Your (Staph Infected) Hand

The story that BoxRec tells is that Pavlik fought Miguel Espino ten months after beating Rubio.

Those of us who followed the sport during that time know that those ten months may have been as trying for Pavlik as any adversity he faced in the ring.

He was supposed to fight Sergio Mora, then backed out. Rumors of a wild lifestyle and drinking problems swirled, though they were never substantiated and Pavlik steadfastly denied them. He was supposed to fight Paul Williams, then he postponed twice, claiming that the staph infection in his hand would not be sufficiently healed in time for the fight.

After the second postponement, Williams grew tired of waiting and signed to fight Sergio Martinez. The two engaged in a Fight of the Year candidate in Pavlik’s fighting home of Atlantic City.

A mere week later, after claiming that his hand would not be healed in time for Williams, Pavlik stopped Espino in the fourth round of an entertaining, one-sided, and far smaller-profile fight.

In 2009, Pavlik fought twice, against Rubio and Espino. The only other year he fought as infrequently was in 2006, when he beat McKart and Pierre. He has defended his middleweight championship against Lockett, Rubio, and Espino, a motley crew at best, one that makes Taylor’s maligned championship opponents (Hopkins, Kassim Ouma, Cory Spinks, and Winky Wright) look like a Hall of Fame lineup (indeed, half of them are legitimate Hall of Fame fighters, and Spinks could conceivably get there with a late career surge). With public perception of Pavlik at its lowest point, Pavlik has a chance to recapture the imagination of fans at the site of his finest hour, against the most difficult challenger to his title to date.

Pavlik may be the ultimate embodiment of the Youngstown fighter but, given that New Jersey is his fighting home, he may want to channel Bruce Springsteen and live up his glory days before they pass him by.