These two men fighting each other Saturday on HBO, Paul Williams and Kermit Cintron, have a persecution complex and a hankering to get into the Floyd Mayweather sweepstakes. Whether they realistically should have such complexes or hankerings is another question. Williams — my favorite boxer — is an HBO darling, making tons of money from the network despite not proving himself as a box office draw, and his name is the least-mentioned from Mayweather’s mouth on his list of potential opponents. Cintron has been on HBO plenty despite some going 1-1-1 on the network in recent years, and even though he beat Alfredo Angulo only to see Angulo get on HBO twice more before him, Cintron turned down one shot on the network so he could fight a no-name in Puerto Rico; and when his name was on the list of Mayweather’s list of potential opponents prior to him settling on Shane Mosley, nothing Cintron had done suggested he was deserving of a shot at Mayweather at that point.

By fighting each other one weekend after Mayweather painted a masterpiece against Mosley, as the follow-on bout to the first free replay of that bout, maybe they can ameliorate their cravings for recognition and Mayweather megabucks. The audience watching Saturday for that free replay should give Williams and Cintron more exposure than they might get otherwise, while being on television the same night as that replay by definition puts Williams and Cintron in the same sentence as Mayweather. Williams is #3 on most people’s lists of the best fighters alive, behind only Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao, and defeating Cintron would keep the beat alive for him to fight Mayweather if Mayweather-Pacquiao doesn’t happen, however remote. If Cintron beats Williams, then he is a far more viable opponent for Mayweather. And you can bet the winner gets on HBO again soon.

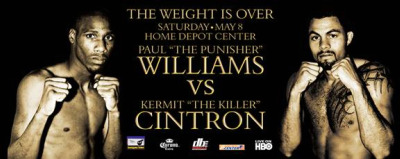

And if none of that works, maybe the winner gets the consolation prize of winning the Sergio Martinez sweepstakes. Both men have unfinished business with the new middleweight champion of the world, after all, with Cintron fighting to a disputed draw with Martinez and Williams fighting Martinez to a disputed win. Even though Williams-Cintron is called “The Weight Is Over” because both men consider themselves welterweights and are fighting at junior middleweights, both men are gigantic for both divisions, with Cintron easily capable of fighting at middleweight and Williams having already done so.

That’s a lot of “what’s next,” though. This fight itself has its own native appeal. One man is nicknamed “The Punisher” and the other “The Killer,” which is as direct as both men are. Williams has become one of the premier action fighters in the sport, owing to his volume punching and lust for hitting-and-getting-hit, while Cintron is a knockout artist who has become more of a technical boxer over the years but ought to be happy to oblige Williams — at least, on the hitting him idea. What happens when Williams hits him is another matter. That’s why Williams is the favorite in this fight, in part.

The other part of it is that Williams has beaten both Antonio Margarito and Martinez, while Cintron lost to Margarito twice and got a gift draw against Martinez that could have been ruled a knockout in the 7th round and certainly should have been a Martinez win on the scorecards. But that doesn’t tell the whole story. As is true of many intriguing match-ups, Williams and Cintron offer something that the other hates, at least in theory. Williams is a southpaw, and Cintron’s best weapon, the right cross, is commonly thought of as the antidote to southpaws. Williams is a pressure fighter, and Cintron hates pressure — Margarito messed him up with it, and even in wins over the likes of Jesse Feliciano and Alfredo Angulo, Cintron demonstrated that he gets nervous when the vice starts clamping down.

But Cintron has gotten better at handling that vice. The first time he fought Margarito, he couldn’t believe Margarito didn’t go down when he hit him with flush rights the way everyone else did, and mentally, he collapsed. The second time he fought Margarito, he survived a bit longer and, at least, he didn’t cry afterward like the first time. When Feliciano pressured him, he panicked again but kept punching and got the knockout. When Martinez got pissed off by the ref’s ruling in the 7th and came after Cintron, he fought back harder. When Angulo — as good a pressure fighter as any — pressured him, Cintron nullified that pressure with sharp boxing and held off a late charge by Angulo, even if Cintron looked a bit shaken by it.

Cintron has evolved in other ways, too. He used to be a pure knockout artist. He has but one knockout in five consecutive fights now dating back to early 2008 — three wins, a loss and a draw, with the KO coming over an opponent, Juliano Ramos, who was there as a sacrifice for Cintron in a showcase fight in his native Puerto Rico. In a 32-win career, only four of his wins are not by knockout. It’s not clear if it’s because of a 2007 right hand surgery and the right hand injury he suffered in the Feliciano fight — conspicuously, Feliciano is the last KO on his record prior to the Ramos stoppage, and coincidentally, it’s that injury that he blamed for calling off a fight with Williams a couple years back — or because he’s fought more often at 154, where maybe his power doesn’t carry up as well. Whatever has happened to his power, it has waned as his boxing skill has waxed. Always faster than he showed, Cintron has increasingly made smarter use of his natural athleticism, kept the proper distance for a big man and benefited from the coaching of Ronnie Shields, the trainer who took him on after Emmanuel Steward dumped him and who appears to have revived Cintron’s career. Cintron, despite being 30, only recently has obtained the air of someone who knew how to box, owing to a late start in the sport and a gift of power that made technical ability secondary. It’s been a career of ups and downs, but coming off the Angulo upset victory and showing the kinds of improvement he has, Cintron is on an upward arc.

Williams’ career has had some ups and downs, too. The win over Margarito was an up. The loss to Carlos Quintana was a down, but beating him in a rematch was a big up, and the stretch of fights he won from welterweight to middleweight, including a domination of a Winky Wright who’d only ever lost close fights, was all up. Yet he is coming off a win over Martinez where he raised public opinion of himself in some ways and lowered it in others. On the plus side, he fought the only style match-up that had given him a loss — Quintana and Martinez are both quick, tricky, counter-punching lefties — on short notice when Kelly Pavlik pulled out of the fight. Badly cut, knocked down and encountering tremendous adversity, he dug deep to pull out the victory, demonstrating what kind of fighting spirit this cat has. And with Martinez beating Pavlik in April, Martinez put himself in the pound-for-pound elite, making Williams’ close win over Martinez even less shameful. On the negative side, Martinez put all of Williams’ vulnerabilities on display, foremost among them how easy he can be to hit. So desperate is Williams for contact that he sometimes gets recklessly out of position and leaves himself wide open to counters, and Martinez dented his previously un-dented chin.

Those defensive lapses could be dangerous against the right hand of Cintron, if there’s juice left in the thing. In fights against opponents who are a bit less awkward and easier to hit than the likes of Quintana and Martinez, Williams has showed more defensive discipline. He comes in moving his head, and he doesn’t have to reach with those long arms of his to make contact. Wright didn’t hit him much at all, and Wright is usually at least consistent offensively. Ultimately his offense is usually his best defense against guys who aren’t good stick-and-move counterpunchers. He swamps people so much with punches from every angle and of such numbers that all they can do is cover up and hope he takes a breath at some point. That never happens. Williams surely trains well, but the man’s genetics are such an odd and dangerous combination. There’s the abnormal height for someone who can fight at 147 — 6’1″ listed, probably 6’3″ in reality. There’s the 82″ reach, eight inches more than the 5’11” Cintron. There’s stamina and stamina and stamina and stamina. He’s also very quick, and when he decides to sit down on his punches instead of overwhelming with the the number of them, he’s demonstrated one-shot power. His coordination and balance, terrible when he first began, have gotten better overall despite the lapses he showed against Martinez.

Given Williams’ assets, and given the assets Cintron doesn’t have, it’s hard for me to imagine Cintron winning. Cintron’s game plan against Angulo, jabbing, moving and throwing straight rights and the occasional left hook, probably won’t be enough against Williams, who won’t be dissuaded from punching in bunches if that’s what’s coming back. Cintron won’t be able to keep his distance against Williams because Williams’ superior height and reach means he can get to Cintron wherever he is, and Cintron’s movement isn’t good enough to play keep-away either. Cintron’s promoter Lou DiBella says Cintron is the biggest puncher Williams has faced yet, but as I mentioned earlier, Cintron’s power has been waning, so counting on power to come through for Cintron probably not do the trick either. Even then, unless Cintron can do some serious damage to Williams and finish him, Williams has shown the ability to make adjustments — eventually against Martinez, he wasn’t getting hit as easily by those counter rights — and rebound from trouble. Cat’s got heart, I tell you!

Meanwhile, Williams is going to be throwing and throwing and throwing and throwing. It’s not hard to imagine Cintron having some success early catching Williams while he’s throwing. But even a psychologically stronger version of Cintron is going to find this throwing very irritating, because everyone does. Moreover, I think Williams is a bigger hitter at 154 than 160, and I think he can hurt Cintron the same way Martinez did. If Williams doesn’t knock him out regular, I think he’ll be stopped either by quitting or because a referee or his corner pulls the plug. Let’s say it happens in eight. And with Mayweather-Williams unlikely, I’ll cross my fingers that we get what is probably the second most-desirable fight in all of boxing behind Mayweather-Pacquiao: Williams Martinez II.

A final note. I’ve seen message board where it’s said that tickets to this fight are still affordable ($200 to $25) and available in abundance for this fight in the Home Depot Center, and a quick try at Ticketmaster suggests that’s true. I have two responses. One, promoter Dan Goossen has been saying he thinks Williams is a draw in California, and my thinking is that he is not — it was Margarito, not Williams, who sold the tickets there for that fight. But then, it’s not as if Williams has a natural home; you’d think maybe he earned some fans in Atlantic City for that Martinez Fight of the Year-caliber war, but I’m not convinced of that either. Two, what is wrong with you people? I would have thought after the Williams-Martinez fight, if not after earlier Williams bouts, that everyone would finally realize this guy is a can’t-miss action star. If you’re a boxing fan who lives near Carson, Calif. and you don’t think seeing Williams live is worth the modest fee — which would also give you what might be a pretty good undercard fight that I’ll mention later this week — I’m not sure what would qualify. Seriously. You must have taken a railroad spike through your head.

[TQBR Prediction Game 2.0 is in effect. Remember the rules.]