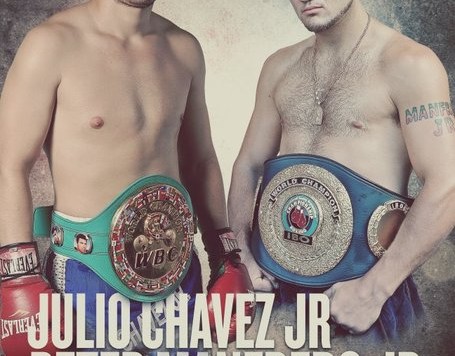

For the second time in 2011, HBO is airing Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. and Saul Alvarez in close proximity on the calendar, with the idea that the two presposterously popular young Mexicans will eventually get in the kind of physical proximity that can be confined by a 20-foot ring in what would be one of the biggest-money fights in boxing. This Saturday it’s Chavez; next weekend it’s Alvarez. The network pulled a similar trick in June, and if all goes according to plan, these will be the last pre-fight fights for the pair.

The opponents — Peter Manfredo, Jr. and Kermit Cintron, respectively — are feasible, if not frightening, threats to the prospects of Chavez vs. Alvarez, and they share a history of having fought on NBC in a time when boxing hasn’t had much exposure on the big four networks. Manfredo is a step down in competition for Chavez, who got quite the unexpected scare in his last fight against Sebastian Zbik. Manfredo is an earnest middleweight, can box a little and more often than not brings it, but he’s also on his last legs. In theory, he’ll put up a fun fight against Chavez — who, at his best, is pretty fun himself — before likely losing.

Manfredo, most famous for appearing on NBC’s “The Contender” back in 2005 and popular in his hometown of Providence, R.I., has lost badly to divisional top-10 names Joe Calzaghe and Sakio Bika but also lesser lights Sergio Mora, Alfonso Gomez and faded Jeff Lacy. He was struggling for several rounds with journeyman Daniel Edouard in his last fight before Edouard foolishly dropped his hands coming out of a clinch and Manfredo clipped and dropped him. Edouard never got his legs back and Manfredo controlled the rest of the fight to get the decision. Manfredo’s best wins are over people on Edouard’s level or a bit better, like Scott Pemberton and David Banks.

Manfredo isn’t blessed with any natural ability of note, and might be more cursed by the lack of it. He isn’t fast, to say the least. He has flashed big power in both hands at times, as he did against Edouard with a right hand and a surprising Knockout of the Year candidate over Walid Smichet via a left hand in 2008. Those, though, are exceptions. What he does have is some toughness, sometimes an excess of it, like when he opted to trade punches toe-to-toe with Bika despite that being a horrible, horrible strategy. And when he wants to, he can box a bit — he puts his punches together well, has a decent jab and can move his feet. I say “a bit” because on the defensive side of the sweet science, he’s sorely lacking, mainly because of that lack of speed. That’s where the toughness comes in handy. He’s been stopped on his feet twice, but clearly doesn’t go down without a fight.

Chavez, too, is about a slow as they come on this level. Talent-wise, he’s marginally a top-10 middleweight. That win over Zbik landed him in the division’s top 10, even if many think he didn’t deserve the decision win. It did reestablish his action bona fides; the John Duddy win got him halfway there, and the Zbik fight did the rest of the work in erasing a pedestrian and boo-worthy bout against Troy Rowland on the undercard of Manny Pacquiao vs. Miguel Cotto. It’s important that Chavez maintain those action bona fides. A certain percentage of Mexican fans are always going to be fans of his because of his dad. Maybe a certain percentage of people hope Chavez can live up to the potential of his genes, but it’s unlikely even with Freddie Roach in his corner that he’ll be very good any time soon, if ever, especially considering his reputation for not liking to train. But as long as he’s in some nice brawls, that’s where he makes his bones with the non-Mexicans and non-optimists.

Chavez might be the only boxer of this level of fame (high) or accomplishment (meager) who gets hit with literally every punch that comes his way. I’m not misusing “literally” there. I don’t think I’ve seen Chavez dodge a punch ever. That, naturally, means that in order to win he has little choice but to stand toe-to-toe and trade, and like Manfredo, he likes punching in combination, so you can see why he gets into some action fights. His body attack is particularly ferocious, the one area where he takes after the old man, even if the imitation is pale. He has occasionally shown an understanding of using his height and length to his advantage, although he often abandons it when the volleys begin to accumulate. His competition hasn’t been stellar, as he has no amateur career to speak of and only recently began to fight anyone with a pulse, but he’s also shown the ability to take a punch so far, the occasional knee wobble aside.

The good news for Manfredo is that Chavez is no Calzaghe or Bika. The bad news is that worse boxers than Chavez have beaten Manfredo. If Manfredo can dodge a few punches for once, or if he can outwork Chavez, maybe he can pull off the upset decision and win with his boxing skills or volume. It’s not as if Chavez has beaten anyone as good as Manfredo, either, setting aside the questionable Zbik win. Manfredo also fared better against common opponent Matt Vanda than did Chavez, back before Chavez hooked up with Roach and improved some. More likely, though, Chavez is going to be too young and fresh for Manfredo for Manfredo to outwork him or dodge enough of his punches, and in the event things are close on the scorecards, Chavez is going to get the edge from the judges.

Manfredo, when not talking about his plans for retirement, has said in the build-up to this fight that he’s aiming for an Arturo Gatti-Micky Ward war and trilogy out of this. That’s a commendable goal. It doesn’t seem likely. But in a fight that doesn’t have much else going for it — it’s unlikely to shake-up the pecking order in the middleweight division, it’s not going to feature a lot of skill and it is candidly a warm-up fight for another fight — if we could get something half as good as Gatti-Ward, it would be worth something more than the ratings that come with Chavez’ name.