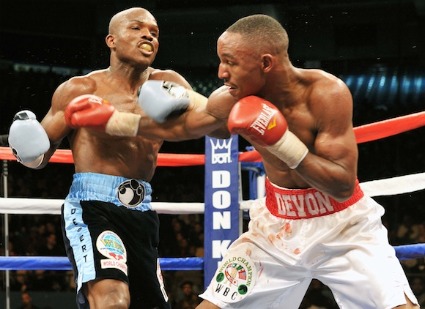

(Timothy Bradley, left, Devon Alexander, right; Credit: Bradley co-promoter Thompson)

For a fight that few people enjoyed, Timothy Bradley-Devon Alexander sure has generated a ton of buzz.

But much of it has been second-guessing, opposition to the second-guessing or people proclaiming validation for their pre-guessing about whether the fight should’ve happened at all.

My take remains basically the same. But given all the ink spilled or pixels pixelated or whatever, the various arguments warrant exploration at length.

In the boxing writer world, count Doug Fischer and Steve Kim among those who thought the junior welterweight fight shouldn’t have happened (at least not this past Saturday) and Kevin Iole among those who regret advocating for it.

First, Fischer, responding to a fan in his mailbag:

…crappy fights, no matter who is involved and how much is at stake, aren’t NOT [sic] appreciated by anyone but the most hardcore boxing purists (such as yourself). It makes sense for a super fight, such as the pound-for-pound showdown that has teased the sports world for the past 18 months, or a truly high-profile heavyweight championship such as Wladdy vs. Haye or Adamek to be made because of the strong public demand. But other bouts between the top dogs of a particular division that are clearly awful style matchups (such as Hopkins-Dawson) have no business being made. Those kind of fights only hurt the sport, especially if they can’t even sell more than a few thousand tickets (as Hopkins-Dawson would be lucky to attract).

I assume he means that those kind of style matchups “are not” appreciated, but mainly I think the example he uses is not apt. Nobody right now wants to see Chad Dawson-Bernard Hopkins, since both men are coming off losses and a bout between them would no longer determine supremacy at light heavyweight. Granted, it would have been a bad style match-up years ago just the same as now, and that would have made it an unappetizing fight in many ways. What I think the opponents of Bradley-Alexander are missing is why some people watch boxing, or any sport. Everyone wants to be entertained. But many people want to find out who’s best. I’ll elaborate momentarily.

Then, Iole:

If the lesson taken away by Greenburg is that he’ll pursue style matchups over matchups of glittering records, than a failed promotion in a city where the fight should never have been held may well have been worth it.

This conclusion sells short the appeal of Bradley-Alexander. It wasn’t just about glittering records. It was about the view that these were two of the most talented young American fighters and two of the best men in one of boxing’s best divisions. (For the purposes of this piece, we shall take as a given that it was a failed promotion in a city where it shouldn’t have occurred. I don’t think anyone really disputes that.)

And Kim:

OK, Bradley-Alexander proved once again that just because you match two of the best fighters in a division, that doesn’t necessarily make it a big fight or event. And records don’t make great fights. Styles do but just matching two guys who have great accolades and skills, doesn’t make it big in itself. Seriously, you can go on boxrec.com and make a multitude of matches with glossy records involved and highly-rated fighters. It really means nothing if those fights don’t involve entities who have been promoted to be known by the public, the event to be marketed correctly and taking place at the right time in the proper venue. There are a lot of facets to making a truly significant event; Bradley-Alexander only fulfilled one of them. That’s why it failed from a commercial and critical standpoint.

I can agree with Kim that the fight wasn’t “big,” per se, but it wasn’t exactly small, either — we’ll touch on the ratings question in a moment. Once more, though, I think this sells the fight itself short, and Kim appears to recognize this himself. He says it “means nothing,” when in fact it means more than that — he acknowledges it contained one element of a “truly significant event,” presumably the “great accolades and skills” each possessed.

But let’s go from there and discuss that element. It is not an insignificant element. Accolades and acclaim are important when it comes to producing a fight that matters, as do the estimation of the match-up, whether a fighter has a real following and how the fight is promoted. Any one of those things can carry a fight. Several of them together do not guarantee a success, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Athletic events where following and styles are lacking can still succeed. Consider:

The NBA didn’t cancel the 2003 NBA Finals, and ABC didn’t refuse to air it, just because it ended up being an ugly style match-up between the small market San Antonio Spurs and New Jersey Nets, rather than a more glamorous match-up between the big-market Lakers and the Celtics. Everyone knew the series would suck, and yet an average of 9.9 million people watched each game. That was a bad figure compared to previous NBA Finals, but it goes to show that about 10 million people will watch the NBA Finals almost entirely because they ARE the NBA Finals, regardless of whether neither team is likely to break 100 points.

For the same reason, people will sometimes watch a fight MERELY because it is significant. Nobody expected Jean Pascal-Bernard Hopkins to be a good fight. If they did, I don’t know where they were hiding. Yet Showtime reportedly claimed Pascal-Hopkins got their highest ratings in three years.

For that matter, Bradley-Alexander wasn’t exactly a ratings failure, given the trends for ratings at HBO.

Last year, by the numbers compiled by The Boxing Truth’s John Chavez in Kim’s, only one fight — one, repeat, one — did better numbers on HBO than Bradley-Alexander. Now, you can point to HBO’s overall ratings trend as an indictment of the network’s overall approach to boxing, and maybe you’d be right. But how could you single out a show that did better than almost all the others as a specific failure, the way Kim did? It makes no sense to me. If anything, the conclusion from Bradley-Alexander should be that, hey, “HBO did better with this one than almost all the others, so maybe this is the kind of thing they ought to be focusing upon.” I know that Kim has used the same reasoning when advocating for certain kinds of fights as it pertains to the only fight that did better than Bradley-Alexander, i.e. Miguel Cotto-Yuri Foreman.

As strange as it sounds, good style match-ups do not produce a fight that does well. Promoter Gary Shaw has caught some deserved flack for pointing to the commercial failure of Diego Corrales-Jose Luis Castillo as some kind of feather in his cap. But everyone in boxing knew that fight would be a great one. And yet, nobody bought tickets for it.

Blind ethnic and regional loyalties can certainly help make a fight big, but not always. Alfredo Angulo is a junior middleweight who produces good action fights and fights in a style Mexican fans historically love, but he doesn’t move tickets. Fellow Mexican Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. has that blind following, so, reportedly, his fight over the past weekend did better numbers on a smaller network than Bradley-Alexander. Interestingly, the same thing that many people are criticizing about Bradley-Alexander — that the fight was boring — was the same gripe that people visited upon Chavez-Billy Lyell. So what matters more: That a fighter be exciting and make exciting fights, or that he does ratings?

Fighters who fight in an exciting manner often do well, but not always, and fighters who fight in a boring manner can do well despite how boring they are. Very few people think Floyd Mayweather fights are fun to watch, but he’s one of the two biggest fighters in the United States; Corey Spinks sold tickets in St. Louis for years despite the fact that hardly anyone enjoyed his fighting style. Meanwhile, Glen Johnson is never in a bad fight, and he’s beloved by hardcore fans, but he’s far from a huge draw or ratings superstar.

Then there’s whether the fight is perceived to be competitive. Pacquiao-Joshua Clottey was not expected to be, so it hurt the fight somewhat at the box office. Pacquiao-Antonio Margarito also wasn’t expected to be competitive, but it did good numbers anyway, largely due to a variety of other factors.

No specific examples are coming to mind, but a priori, a well-promoted fight is usually going to do better than a poorly-promoted one, although not always — sometimes a fight is so undesirable no amount of clever promotion can turn it into a success.

The truth is, all of these things matter. My remark about not wanting HBO to pay for Tomasz Adamek-Kevin McBride might have been taken as a slight toward that fight. I don’t at all doubt that it will be exciting for as long as it lasts. I don’t at all doubt that it will sell tickets, since Adamek is good at that. I don’t have any interest in buying the fight because it is meaningless and not expected to be competitive, but I could see why someone else would, since I’m a fan of Adamek overall. But is that really what we all want — a series of meaningless or one-sided fights that are fun to watch and sell tickets? Or do we want those fights to MEAN something outside of whether they are exciting and sell tickets?

I think there’s room for all of these things — ideally, all together, but sometimes, you can’t get that. There are really just a handful of fights that offer “all of the above,” so sometimes the options are “a lot of some, none of the rest.”

I wanted to see Andy Lee-John Duddy prior to its postponement despite the fact that its outcome would say next to nothing about who’s best at middleweight because I thought it would be a good slugfest. I wanted to see Bradley-Alexander regardless of whether I thought it would be a poor style match-up; I was optimistic it wouldn’t be, and while I was wrong, it wasn’t the most important thing about that fight to me. What mattered is I wanted to find out who was the best between those two talents. And judging by the ratings, I wasn’t alone. Maybe the outcome of this fight will turn off more fans than it creates, as Michael Rosenthal suggests here, but I think that’s hard to predict — some fights that I suspected would be bad for the sport, like Mayweather-Juan Manuel Marquez, appeared to have the opposite effect. I generally am of the view that bouts featuring the best against the best are good for the long-term health of the sport, regardless of whether each and every one of them is exciting, because that model helped suck customers away from boxing and to mixed martial arts, where Anderson Silva is something of a draw despite the fact that he often faces criticism for being in boring fights because he’s the best and people want to see him challenged by the other best.

Iole acknowledges that it’s unfair to criticize HBO for making a fight between two of the best men at the weight. Good for him. The fact of the matter is that no matter what fight gets made, or how, somebody is going to find fault with it. That’s fine. Everyone’s entitled to their view, and it’s good for boxing writers and fans to critically scrutinize the moves of the powers that be in the sport. That doesn’t mean that the criticism is fair or right. One of the raps on HBO has been that it wasn’t making fights between the best fighters. So HBO did it with Bradley-Alexander, and I disagree with Iole’s view that we should switch to a system where only the most entertaining fights are made. You know what would happen if HBO did that, right? I promise you, there would be people throwing fits that their HBO subscription went to one-sided and meaningless — but entertaining and ticket-selling — affairs like Adamek-McBride, rather than bouts that are about something and viewed as competitive, like Bradley-Alexander.

There is a secondary strain of discussion here about the “how” that’s more fair, I think. HBO paid a hell of a lot for Bradley-Alexander and even guaranteed the loser a big pot of money for his next fight. As always, it’s hard to imagine how HBO needed to pay QUITE that much, since Bradley and Alexander almost assuredly weren’t going to make anywhere near that amount fighting each other or a different foe on Showtime or anywhere else, Top Rank’s CBS deal notwithstanding. And with Alexander appearing in the eyes of many to beg out of the fight — and with no evidence of nerve damage from the head butt and all the anecdotal material out there like Alexander suddenly being able to open his eyes once the bout was halted, it’s my opinion that he did — the idea of Alexander deserving very much money for his next fight becomes somewhat bothersome.

I wouldn’t suggest that the bothersomeness is unwarranted, but I do think there’s a slight mitigator here. Remember when everyone was clamoring for a junior welterweight tournament featuring Bradley, Alexander, Amir Khan and Marcos Maidana? Well, guess what? Under that format, Alexander ALSO would have been guaranteed money, probably still a lot of it, for losing. Since Alexander-Maidana and Bradley-Khan appear to be the most likely next bouts for Saturday’s combatants, the idea of Alexander getting guaranteed money for that fight in and of itself isn’t any more offensive than the idea of a junior welterweight tournament rewarding the loser’s bracket. Assuming, of course, that Alexander-Maidana and Bradley-Khan come off.

Lastly, there has been discussion about whether this fight would have been bigger later rather than now. I’ve weighed in on this a fair amount, so I won’t revisit it much. Golden Boy and Top Rank both seem to think they can do better with Bradley than Shaw has, and given that he’s a free agent soon, maybe they’ll get a chance. (Funny aside: When GBP has talked publicly about TR signing away TR products when they become free agents, TR has thrown out some rhetoric about lawsuits. Doesn’t seem to give TR pause to do it to someone else, though, I guess.) I think Bradley is always going to have limitations as a potential star, namely due to the fact, as Iole notes, that “those who do know him are becoming frustrated by the prevalence of head butts in his fights.” But let’s say GBP or TR succeeded where Shaw failed. We’re talking about a multi-year project here. Does anybody want to see the #1 junior welterweight in the world, as Bradley was even prior to the Alexander loss, spin his wheels for years not fighting the #2 or #3 guy in the sport while promoters undertake a potentially quixotic quest to turn him into a star? I sure as hell don’t.

I’ll give the last word(s) to some people other than me, so I don’t feel so lonely disputing the arguments of good journalists like Iole, Fischer and Kim (not that these two dudes are specifically arguing with those guys the way I am).

Here’s David P. Greisman:

The top fighters must still keep facing each other, both for pride and for money, in order to prove themselves as the best and to establish themselves as worthy of attention from fans, networks and ticket buyers.

The promoters must keep putting their top fighters in against tough opponents on the chance that they could hit it big. You can’t ride the horse to the prize if you don’t let it out of the gate.

And the networks must keep paying for fights between top fighters – so long as there’s the possibility of it being worth it. Bradley-Alexander was a logical investment for HBO, a match that just in being made had pleased the people who pay subscription fees to see the good fights and good fighters….

Timothy Bradley is good. Devon Alexander is good. Their fight was not.

HBO paid seven figures to Bradley and seven figures to Alexander. The final product didn’t match the price.

But it was a pairing worth making and a price worth paying.

And here’s Jake Donovan:

Sometimes, anticipation and buildup can help transform a fight into an event. There are even some fights that deserve such buildup, rather than its participants meeting too soon and for too little.

Then there are occasions where some fights simply have to happen at the time its being offered, just because it’s a fight that makes sense for the sake of progression – for the fighters and for the sport.

At no point was a fight between Tim Bradley and Devon Alexander ever going to break box office records. It was never going to be that fight that left boxing fans talking for weeks, or even one that was going to bring new fans to the sport.

It’s a fight that was crucial to the continued shaping of the 140 lb. division.

It may have landed in the wrong venue. It may have been tough to watch, and disappointing in the way it ended.

None of that changes the fact that it’s still a fight that had to happen, and at the time it was offered.