The words “dirty” and “crafty” are often interchangeable in this great sport.

One might be less likely to decry the not-so-sweet portion of the sweet science if brought up, for example, in a town like Gary, Indiana — a town created from the flattened remnants of sand dunes for the specific purpose of building steel manufacturing plants.

A few years before Anthony Florian Zaleski was born in 1913, a writer named William B. Hard made public the dangerous and poor working conditions in steel mills in nearby Chicago with an article entitled “Making Steel and Killing Men.”

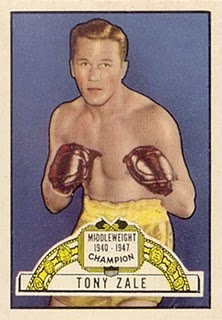

And making steel in a steel mill was basically the story of Tony Zale’s childhood.

When he was just two years old, his father was run over by a car and killed while bicycling to the drugstore, leaving his mother to raise a handful of kids alone.

Like many children born into immigrant families in Gary’s Central District, Tony worked the mills with his older brothers when he was old enough to. He would later say, “It seemed like I worked in the steel mills since I was weaned, breathing the burnt air, catching [with a bucket] the hot rivets that could burn a hole right through you if you missed.”

His brothers boxed as amateurs right around the time he was in parochial school, and at 15, he fought his first amateur fight.

Tony lost, and badly.

But when Gary began holding Golden Gloves tournaments in 1930, he wound up winning the welterweight championship, and would win three more titles in the following years. In 1934, he represented Chicago in the Intercity Golden Gloves at 175 lbs., and finished with over 200 amateur bouts (most at 160 lbs.) before his 20th birthday.

Turning pro in June, 1934, Zale demonstrated little finesse and, at that time, didn’t seem like a big puncher. What was clear even early on in his career, however, was his work ethic outside the ring, and his savage tenacity inside of it.

He could be out-boxed, however, and was fighting sometimes two and three times a month — usually injured — and having worked at the mill at least part-time, nearly non-stop. In 1935, instead of bowing out to rest an injured muscle in his midsection, Zale simply slowed his progress and went back to work, demanding more taxing positions to toughen himself up. When he returned to the ring in 1937, his record was 17-9-1, but he was well known in Chicago boxing circles.

His first KO loss to Jimmy Clark in February, 1938 was avenged four months later, and again that October, where Clark hit the canvas a total of 11 times.

By the time Zale rose from a 1st round knockdown to earn a 10-round decision over Al Holstak in January of 1940, he’d already hooked up with the former managers of welterweight great Barney Ross, Sam Pian and Art Winch, who had guided Ross to three world titles.

“The Man of Steel” earned three knockout wins before again facing Holstak for the NBA middleweight title in July, 1940. After the bout, Holstak claimed to have broken his left hand early on, to which Art Winch replied, “Maybe so, but Tony broke his heart.” Tony was quoted as crediting his brutal body work for the win.

With the win, Zale essentially became a part-titlist, as Ken Overlin had recently defeated Ceferino Garcia for the other half.

A month later Zale was soundly outmaneuvered by capable contender Billy Soose over 10 rounds in a non-title affair. But complete training camps allowed him to decision ranked former middleweight champ Fred Apostoli in November, then stop Great Lakes-area middleweight Tony Martin in January if ’41.

Two subsequent bouts against Steve Mamakos showcased Zale’s grit and determination, as he knocked Mamakos down to win a close first fight, and rallied to stop him in round 14 of the rematch while clearly down on the cards, making his first defense of the NBA title.

His warrior reputation continued in a third fight with Holstak when he again tasted canvas in the 1st, but roared back in the 2nd to knock Al down eight times before the stoppage. And he continued on with two more knockouts over Ossie Harris and Billy Pryor.

Zale was matched with contender Georgie Abrams, who got the shot (complete with NYSAC belt on the line) on the strength of three wins over NYSAC middleweight champ gone north, Billy Soose.

Reportedly, Tony mugged the heck out of Abrams, using his forearms, elbows and whatever worked — even appearing to thumb Abrams’ eye, both of which were badly swollen after he lost a 15-round decision to Zale. Thus, Tony Zale was middleweight champion of the world.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked a week and a half later, imminent U.S. involvement in World War II brought title fights above lightweight to a halt. This caused Zale to follow through with a light heavyweight non-title showdown with Billy Conn, who was out to prove he hadn’t lost much in the wake of his crushing loss to Joe Louis in their first bout.

After dropping a 12-round decision to Conn, Zale joined the Navy and served essentially as a fitness instructor, rather than fight in exhibitions or teach boxing. Of his stint in the Navy, Zale would say, “I couldn’t box with the kids. I have to wade in and punch, I can’t hold back. If I started pulling punches to protect the kids, I would never get over the habit. I would have lost my punch. So I simply didn’t fight.”

Upon returning, Zale reportedly appeared a little slower and definitely rusty. But from 1946 on, all of his wins would come by stoppage.

He tore through a few non-ranked, unimpressive guys before signing to fight brash young New York middleweight Rocky Graziano at Yankee Stadium in September, 1946. And in front of almost 40,000 people, a monster of a trilogy was born.

Zale floored Rocky, then Rocky flattened Zale and kicked the crud out of him so badly that Zale walked to the wrong corner. But in round 6, Tony sprung from his corner, hurt Graziano and finished him with a savage body assault.

The steel-milling toughman stayed in the ring, albeit against tune-up opponents to stay busy, and Graziano had his license revoked in New York for failing to report attempted bribery, leading their rematch to take place in Zale’s backyard: Chicago.

A rematch fit to challenge the first fight in brutality broke records for indoor fight gate money. With over 18,000 fans watching, both guys were swollen, lumped up and bloody by the 4th round. Zale had already scored a knockdown in the 3rd and was looking at a repeat, before Graziano, with eyes almost swollen shut, unleashed a volley in round 6 that forced referee Johnny Behr to stop the fight.

While Zale initially protested, his character was such that he later refused to allow anyone to question the legitimacy of Rocky’s win.

However, a rubber match settled the issue, as Graziano was dropped hard in a quick-paced and entertaining 1st round, and twice more in the 3rd to end the series.

In less than two years, both spilled a few Zales and Grazianos-worth of blood.

Zale’s last fight, a loss to Marcel Cerdan (with his lover Edith Piaf looking on ringside), simply cemented his reputation as an in-ring soldier. With Cerdan out-fighting Zale and the latter always in pursuit, Marcel began favoring his right arm and appearing to fade. But in the 11th, the French scrapper dropped Zale with his good arm and followed up with a barrage that had “The Man of Steel” falling all over himself in his corner. And in his 87th bout, Zale never emerged to begin the 12th.

Tony would develop into something of a local legend in Gary, as he became active in the community headed a number of organizations and clubs, like a veteran rehabilitation program. He was also named “Sportsman of the Decade” in Gary.

That’s without mentioning that he was involved in three Ring Magazine Fight of the Year affairs in a row, was named Ring Magazine Fighter of the Year in 1946, and was the third ever middleweight to regain the crown.

In 2003, he was appointed #41 on Ring’s 100 Greatest Puncher’s list.

In terms of in-ring legacy, his trilogy with Graziano is, to this day, consistently mentioned on lists of “Greatest Rivalries” and “Greatest Trilogies,” despite most fans alive today never having seen a moment of the first two bouts.

As an old man, Tony Zale was asked what he thought about Graziano’s notoriety. He replied, “It doesn’t bother me ’cause I know I’m the boss. He knows I’m the boss too.”

Read more from Patrick Connor at Beloved Onslaught. Follow him on Twitter @integrital.