There existed a time, not so long ago, when amateur boxing amounted to much more than an unsatisfying hors d’oeuvre to the main course of the professional ranks.

It’s not that amateur pugilism cannot be entertaining and fun to watch, but the current system almost seems to actually discourage action fights with quick stoppages and point per punch regulations.

This current period of general disinterest in the American amateur game in particular may not last long though, as reports say the U.S. will be sending representatives for nine of 10 weight classes to the London Olympics this summer. Even so, the attention will likely pale in comparison to the 1976 or 1984 U.S. Olympic Boxing Teams.

In itself, that’s not an insult — those teams were legitimately great, and boxing was still a household sport at the time. But past that, amateur boxing back then was arguably better preparation for the professional ranks than it is now. Quick stoppages and emphasis on landing pecking blows that simply score points wouldn’t seem to do fighters any favors when quality is king in the pros.

Nonetheless, one amateur boxing institution that over the years has conveyor belted out very good and truly great fighters is the New York Daily News Golden Gloves. Jose Torres, Emile Griffith, Johnny Saxton, Riddick Bowe, “Sugar” Ray Robinson — all New York Golden Gloves champions. And they were all known for participating in solid action fights before turning professional.

*******

Born the fourth of six children and growing up in a rough area of the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, Mark Breland was not only a record five-time Golden Gloves champion in New York, but also member of the aforementioned 1984 Olympic squad.

From the time he wandered into the Broadway Gym at 9-years-old, until shortly after he won a gold medal in Los Angeles at the ’84 games, Mark was trained by George Washington. But capturing a title in the 1979 A.A.U. Junior Olympics is what persuaded Breland to stop pursuing football in high school and pick up boxing full time.

Upon turning pro in 1984, Breland was already been widely considered to be one of the best American amateur fighters ever, much less alive. Though most amateur records are unsubstantiated, Breland reported a record of 110-1 when he left the ammies. The lone loss was to Darryl Anthony at the U.S. Nationals in California on points. Then president of boxing at Madison Square Garden, John Condon, said of Breland, “He’s easily the best amateur I’ve ever seen. Even better than Leonard.” Ray Arcel, famed trainer, gushed, “He’s a natural. He can box, he can punch, he knows how to make an opening, he picks off punches good, and he has a grace and rhythm to go with it. And he knows how to relax. Breland has the making of a truly great fighter.”

He had big plans to, as he’d already starred in a movie called “The Lords of Discipline” in ’83, and wanted to get back into acting after his pro career was done.

His 6’2″ frame had already garnered plenty of comparisons to Tommy Hearns, with whom he’d sparred a number of rounds while expecting to be picked up by Manny Steward as a professional. However, it was Ray Robinson that he’d tried to emulate with his style. Breland had sought out and bought a number of Robinson’s fight tapes and studied them dilligently. Said Mark, “He threw punches from all angles, body shots, a lot of combinations, not just one-two. I tried to learn the different moves that he made. I look up to Sugar Ray Robinson, but I just want to be like Mark Breland.”

His debut at Madison Square Garden had been planned months in advance, and not wasting any time, Breland actually defeated his first future champion, Steve Little, in just his third pro fight. Mysteriously, his knockout percentage clearly improved as the class of his opposition did the same, and he either smashed through or out-classed journeymen and undefeated prospects alike. It likely helped that he was fully immersed in the world of pugilism, nursing close friendships with New York boxing icons like Eddie Gregory, Yoel Judah, and Mike Tyson. And he’d hooked up with trainer Lou Duva and his son, promoter Dan Duva.

In January of 1986, Breland went 10 rounds for the first time, toppling 24-0 Troy Wortham in Pennsylvania in a “Wide World of Sports” main event supported by Tyrell Biggs vs. James “Quick” Tillis.

Two fights later, Mark Breland avenged his only amateur defeat by stopping Darryl Anthony in three rounds. The AP wire report stated, “…[Breland] cut Anthony over the left eye in the first round and then knocked him down with about a`minute left in the third with a right hand. After Anthony got up at the count of three, referee Tony Orlando summoned a ringside physician who stopped the fight.”

Another two fights down the road, Breland halted undefeated Ugandan John Munduga in the 6th. After having his way with the more experienced 24-0 fighters, Munduga launched an offensive in round 6 that walked him into a brutal uppercut that wobbled him badly, and he was finished off by Breland’s dangerous right hand. Following the win, Breland said, “His plan was to come forward, hit, and get hit. I knew he was a good puncher, but I punch pretty good, too. His game plan was taken away and you can’t adjust in the ring unless you are real smart.” Breland’s rise got an extra boost that night, as Munduga was rated top-10 by the WBA at both welterweight and junior middleweight.

In February 1987, Breland won his first world title fight, capturing the WBA welterweight belt vacated by Lloyd Honeyghan in protest of apartheid, as the WBA had mandated that Honeyghan face South African Harold Volbrecht, whose most notable showing to that point was a stoppage loss to Pipino Cuevas in 1980. In front of a lively Atlantic City audience, “Breland pinned Volbrecht near the ropes and hurt him with a right to the face that made Volbrecht lean to the ropes. Breland followed with a right and a left, then landed a chopping right right to the jaw that dropped Volbrecht to his knee in a neutral corner. Volbrecht then slumped to the canvas and referee Tony Perez counted him out at 2:07 of the seventh round.”

After a five month hiatus, the former Olympian then traveled to Italy to decision Juan Rondon over 10 rounds in a non-title affair, enjoying his success along the way.

But just over one month later, in August of 1987, Breland lost his WBA welterweight title to Marlon Starling in a fight where he won rounds early, broke Starling’s nose, and appeared sluggish late, seeming to succumb in the 11th round as much from exhaustion as being actually hurt.

Two fights over the next eight or so months sent him to a rematch with Starling in which Marlon appeared to hurt Breland early and sting him repeatedly, but Breland worked hard, out-throwing and out-landing Starling quite clearly. Fans in attendance at the Hilton in Las Vegas booed the draw verdict nonetheless, feeling as though Starling had won. Ultimately, Breland had failed to win back his title.

Starling’s controversial bout against Tomas Moliares three months later saw him get counted out following a shot after the bell, and the subsequent fallout had Molinares vacating the belt, which lacked an owner once again. Breland jumped on the opportunity, and “barely broke a sweat” in trouncing Korean Seung-Soon Lee in less than a round to win back the belt.

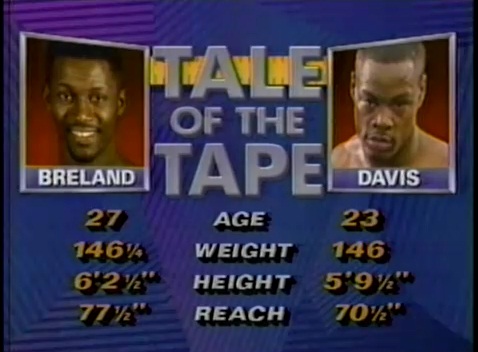

Four defenses followed, all by TKO, included making an undefeated Rafael Pineda quit claiming foul, and a vicious three-round destruction of contender and former champ Lloyd Honeyghan. A nagging knee injury kept him fairly inactive, but a seven-fight KO streak brought him to 27-1-1 (20 KO) and set up a showdown with prospect Aaron Davis in 1990.

*******

Raised in The Bronx, Aaron “Superman” Davis wasn’t exactly a stranger to the New York Golden Gloves himself. Davis went to the finals at 147 lbs. a few years in a row, winning once in 1986. Under normal circumstances, that may have given him some type of advantage in the pro ranks — just not when put on a collision course with a five-time Gloves champ, it seemed.

Unlike Breland, Davis rose through the ranks with far less money and support behind him, and few big name friends in comparison. That also meant fewer headlines and media coverage than the highly accessible Mark Breland.

Through his first 16 pro fights, Davis fought six times in France, usually defeating foes unfamiliar to most boxing fans, but often headlining or co-headlining at the Felt Forum in New York.

In June of 1988, Davis stopped Tyrone Moore in the 8th round of a scheduled 10 round bout while headlining at the Felt Forum. “Superman” Davis floored him once in the 6th and twice in the 7th, then clobbered Moore in the 8th, forcing him to stay on his stool for round 9, according to The New York Times.

Five more wins against relatively unimpressive opposition pointed him towards a match with 35-9-2 Luis Santana, with Davis claiming he’d turned down an opportunity to face IBF titlist Simon Brown due being promised a shot at crosstown rival Mark Breland’s WBA belt. A “punchless showing” against Santana, as reported by Long Island paper Newsday, cost him his shot at Breland.

Two fights later, Davis again failed to impress in a ho-hum showing in 10 rounds against Gene Hatcher, who only a few fights prior had been knocked out in 45 seconds by Lloyd Honeyghan, setting a record for shortest world title fight at he time.

Three more fights and an overly fortunate decision win against so-so New Jersey staple Curtis Summit steered Davis toward a title shot with Breland, who was looking to make a fifth defense of his WBA welterweight title that he’d recently won back. With the win, Davis became the #6 ranked contender in the WBA.

Heading into the Breland fight, Davis was 29-0 (18 KO).

*******

Curtis Summit, who Davis had just beaten, would later claim in the book “The Gloves: A Boxing Chronicle” that he knocked Breland out during sparring while in training camp for the Davis fight, and that the entire training camp for Breland had essentially been a disaster.

Aaron Davis, on the other hand, came off bitter and feeling snubbed by press in the lead-up to the Breland match. An AP wire via the Victoria Advocate reported Davis as saying, “I think he’s looking past me, that’s why I’m in the best shape I’ve ever been in for this fight. This fight is definitely not going the distance. Everybody’s looking past me. I’m glad about that. I’m going to come out of this fight the winner.” And regarding his lackluster showing against Summit, Davis said, “I never should have took that fight. I wasn’t myself.”

As for Breland, his reply was, “I don’t look past no one. I’m in the greatest shape I’ve ever been in. I don’t go out to knock no one out. The name of the game is to win. I look to box and punch. If he comes brawling in, he’ll get hit.”

And Davis’ final word: “I’m not gonna knock him out early. I’m gonna beat up on him.”