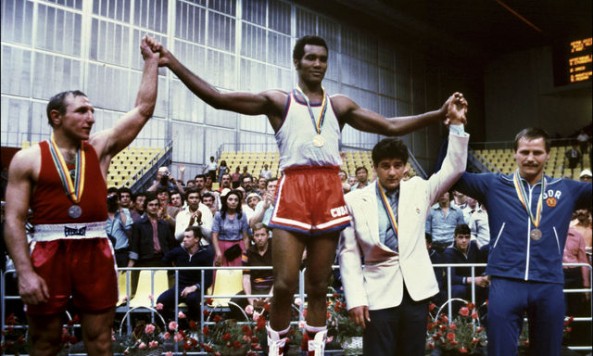

(Photo: gold medalist Teofilo Stevenson [center], silver medalist Pyotr Zaev [left], bronze medalist Jurgen Fanghanel [right], 1980, AFP/Getty Images)

Cruising into the guts of Olympic boxing this year, many of us boxing fans still feel foggy-headed as to whether or not we’re supposed to care, and if we are, why.

The numbers are in, though, and overall interest in this year’s Summer Olympics is up significantly compared to the last few, and at least a portion of that extra attention has been paid to the boxing branch.

Over the last half-decade, boxing seems to have closed the technological gap between it and better organized sports, and especially in terms of social media. And given this year’s Games’ “Twitter Olympics” nickname, perhaps boxing fans have simply been able to keep up with the goings on in London much better than in the past; it probably doesn’t hurt that boxing isn’t only being shown at late-as-hell o’clock in the U.S., but more schedule friendly afternoon and evening times.

Despite the apparent divergence of amateur/Olympic and professional boxing in recent years, pundits still scout the Games for the next potential star or fight celebrity in the international talent pool. For many fighters, the opportunity to slingshot their way to stardom on the back of an Olympic medal is the ultimate, more long-term goal.

But to every Olympic athlete, the podium is the immediate end.

*******

Upon boxing’s introduction to the Olympic style competition in the 7th century B.C., the famed Olympic podium, where medals are handed out, likely looked a lot different than the three-tiered podium that exists to day. In fact, in that time, the word “podium” was meant to describe something that resembled a pulpit or balcony, and medals weren’t placed around the necks of victors.

Instead, the best of the best available had their names written in the lifeblood of the Games:

Onomastus of Smyrna, the first ever boxing champion at the 23rd Olympiad in 688 B.C., when pugilism was initially introduced, was credited with writing the rules of ancient boxing; the boxing prodigy Glaucus of Carystus was the subject of the first verifiable example of a Grecian ode; and the last reported athlete of the Ancient Olympics, boxer Aurelios Zopyros of Athens.

The organized duomachy of primeval days amounted to a much grittier version of what we see today, though.

It wasn’t until 1904 that boxing was reintroduced to the Olympic Games — then commonly known as the World’s Fair games for mostly political reasons. But boxing in the 1904 Games epitomized the borderline athletic jingoism that many detractors have used as fuel to discredit the entire system: only American fighters competed, thus only American fighters saw the podium.

Oliver Kirk won gold at both featherweight and bantamweight, where in the 3rd round he stopped George Finnegan, who won gold at flyweight. To date, Kirk remains the only competitor to win gold medals in different weight classes of the same event, while three other Americans won medals in two weight classes — a feat that hasn’t been rivaled since (and likely cannot be).

But none of the Americans stood on any sort of podium in 1904. It wasn’t until the Commonwealth Games in the 1930s that the multilevel podium as we know it was used, and not in international competition until the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, according the International Centre for Olympic Study at the University of Western Ontario. To that point, the King and Queen of England would hold the most elevated of positions at the Commonwealth Games as they handed out medals.

When the International Olympic Committee borrowed the idea, some of the best athletes in the world got a taste of the throne, in effect being exalted to a position that was, to that point, only fit for royalty.

That amateur-to-pro transition has become, if nothing else, far less smooth in recent years where Olympic medals are concerned, and for a host of reasons: headgear that seems to get fluffier every four years, an abstract scoring system, lack of faith in the integrity of the overall system (often for good reason), and so forth.

It’s not as if every bout was a thriller in Olympics past, but the mechanics and logistics of the sport resembled the pro game much more closely than the current system, which probably dulls the likelihood of a medalist excelling in the paid ranks.

Consider that the only current top sell in boxing that has sniffed a recent Olympic Games is Miguel Cotto, who lost in the first round in 2000. Guillermo Rigondeaux, who won gold that same year, is just now flirting with the idea of becoming truly elite. His drawing potential remains to be seen, though.

Nonetheless, the Olympics, taken at face value, offer an opportunity for the the best amateur fighters in the world to survive a bracketed gauntlet of international competition and, upon standing on the podium, be considered one of the best few fighters in the world.

The podium is everything. Though many fight for country, state or whatever politically-convenient territory they represent, full recognition is near impossible without having been elevated on the podium — a sanctum that the peasantry cannot reach in the moments of elite athletic high tide.

Unsurprisingly, a controversy or two have prompted a new wave of calls for boxing to be dropped from the Olympics because of the aforementioned trust issues and dissatisfaction with the rules. So maybe Olympic and professional boxing are more alike than we realize, and in more ways than one.

The Olympics remain one of the biggest stages a fledgling pugilist could ask to squabble on, and more exposure than most professional fighters get over the course of a career. That few recent medalists have become pugilistic sensations can be attributed to a number of factors like the fluctuating popularity of boxing, fewer participants, and little network and sponsor participation, solutions to which are likely more complex than subtracting an opening for young blood to get feet in the door of the boxing public’s consciousness.

Even shy of seeing anyone hit the podium, this year the Games have taught us that there’s still a lot of ability out there in the boxing world, and often lurking in the places we expect least.

But there’s still a lot of fighting to be done. And the podium awaits.

Feel free to follow Patrick on Twitter at @Integrital.