So continues our marathon coverage of one of the biggest fights of 2012, Manny Pacquiao vs. Timothy Bradley on June 9 on HBO pay-per-view. Previously: the stakes of Pacquiao-Bradley. Next: a preview of the undercard.

Boxing’s power couple, Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather, have each, since their rise to the top of the sport, mostly fought souls with at least a chance of having been heard of by the casual or non fan. Shane Mosley, Miguel Cotto, Juan Manuel Marquez — these men all had name recognition, one way or another. Most of the names also had at least some kind of following; Victor Ortiz, who was on the obscure end of Mayweather opponents, at least had been a proven ticketseller and television ratings draw. The one real exception to the rule has been Joshua Clottey, the nearly anonymous Ghanaian Pacquiao fought in 2010.

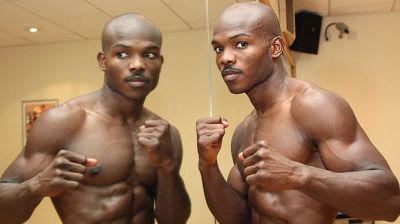

Enter Timothy Bradley as the latest exception. Even with HBO’s 24/7 documentary program introducing him to the casual fan in recent weeks, a typically befuddled response to the comment “Pacquiao’s fighting Timothy Bradley this weekend” is, “Who?”

Bradley is a name to hardcore fans. But for the less devoted, he bears further introduction.

Rise To Prominence

First and foremost, Bradley is an authentically good boxer. He’s the #1 junior welterweight in the world — one division lower than Pacquiao — and, on some lists of the best boxers in the world regardless of weight class, in the top 10. Some boxers get into that top 10 with a signature win, like a win over someone else in the top 10. Bradley has attained his status by beating a series of excellent, but not ultra-elite, opponents.

He burst onto the scene in 2008 with a fight against Junior Witter. His name was known before that; he’d appeared on Showtime’s program for prospects, ShoBox, and thrived. (One of his pre-Witter wins was against then-unheralded Miguel Vazquez, in what now — after Vazquez has gone on to some big wins — looks like one of the better names on Bradley’s resume.) Fighting Witter wasn’t the original plan. Bradley hoped to have his breakout fight against Jose Luis Castillo, a big name from his all-time great fight with Diego Corrales, but Castillo, as had become his fashion, failed to make weight and the bout was called off. Two months later, with a mere $11 in his bank account, Bradley went to England to face Witter. Witter had earned a rep as a “much-avoided” fighter, with a tricky style, who had tried unsuccessfully to get fellow Brit and big star Ricky Hatton into the ring.

What would unfold was one of the upsets of the year. Bradley, in that fight, never flashed the kind of all-around ability that he would come to later. His punches were sloppy and awkward. But he did show the world that he was extremely tough, unwilling to back down and generally just wanted the win more than Witter. That trait — indomitable will — has never vanished from Bradley’s makeup since.

He would go on to beat a series of top-10 junior welterweights, or, at least, no one worse than a fringe contender. A “welcome home” kind of win against the least of his subsequent opponents, Edner Cherry, was followed by a very difficult victory over Kendall Holt. Holt decked Bradley in the 1st round, and it was no love tap: Holt is one of boxing’s top punchers when he’s on his game, and he caught Bradley clean. Bradley would try to rise, only to find his legs were not feeling the same way about that as he was, so he returned to a knee. He beat the 10 count, survived the round, and almost immediately set about getting in Holt’s space, unnerving him and outworking him. Holt would once more hurt Bradley in the 12th round, but Bradley would once again survive for his second big win. It’s not easy for boxers to twice survive almost getting knocked out in the same fight, but Bradley showed he was made of some pretty heavy metal. If the Witter win made Bradley someone to think about, the Holt win was confirmation that the right way to think about Bradley was as a helluva fighter, not a one-win pony.

A win over top lightweight Nate Campbell followed in a fight that ended early due to a Campbell cut, with the result being overturned later because Campbell’s cut in the fight came from a head butt, rather than a punch. A win turned into a “no contest.” This would mark the prominent beginning of a disturbing pattern for Bradley: He had opened a cut on Holt’s eye with a head butt, too, but the Campbell head butt called serious attention to Bradley’s tendency to lead with his noggin. Among hardcore boxing fans, Bradley’s identity is nearly as defined with his head butting as it is with anything he’s accomplished as a boxer.

After the Campbell fight, Bradley beat Lamont Peterson, a hard scrabble fighter with a lot to prove — but as well and as hard as Peterson fought Bradley, Bradley had that one extra gear. This would be Bradley’s best action fight. The Witter fight entertained because it surprised; the Holt fight entertained because Bradley showed such guts; Bradley-Peterson entertained because it was a high-level brawl with a ton of punches exchanged. It was also probably Bradley’s most complete performance. Bradley’s punches were straight and true, and his defense, despite getting hit plenty, was astute. No longer was Bradley just a fast, strong guy who outworked and out-willed his opponent. He was turning into an all-around fighter.

Bradley was getting good enough to mention as a potential opponent against Pacquiao or Mayweather by now, so he moved up one division to welterweight, where both resided. He also moved from Showtime, which had been a big backer of his career, to the bigger HBO. The results, against fringe contender and low-skilled brawler Luis Carlos Abregu, was not convincing — Bradley won definitively, but didn’t look as strong at the new weight and turned in a relatively sloppy performance. It would be his only fight in 2010.

In 2011, he returned to junior welterweight for a fight that a large number of hardcore fans were asking for, against fellow top junior welterweight Devon Alexander. Alexander and Bradley both wanted to stake their claim as the best young American fighter, but as has always been the case, Bradley showed that he wanted something more than his opponent did. From the start, Alexander looked skittish, and Bradley bulled ahead. The fight would end in the 10th when Alexander couldn’t (or didn’t want to) continue after a Bradley head butt. Bradley would get the win, but because the fight was boring and ugly, massive new acclaim didn’t follow.

Road To Pacquiao

A Bradley showdown post-Alexander against Amir Khan, who had beaten Marcos Maidana in his previous fight, would have completed a series of fights between the top four junior welters. Bradley, who had sought the fight with Khan, was offered a career-high payday. But by this time, Bradley was trying to part ways with his promoters Gary Shaw and Thompson Boxing. Under that promotional team, Bradley had worked his way onto the networks and had earned some very nice paychecks. But he also notoriously couldn’t get fans to pay to see him live. Shaw would buy up tickets to his shows in Bradley’s neighborhood to make it look like he’d sold out a fight, but nobody was convinced. The Bradley-Alexander fight was held at the Silverdome in Michigan, and while that got more money for everyone because of the Silverdome offering up some nice cash, it also became a symbol of Bradley’s lack of drawing power, fighting in a mostly empty arena, and a symbol as well of Shaw’s shortcomings as a grassroots promoter, to hold a fight far from either man’s fan base.

Taking the Khan fight would’ve meant staying with his promotional team. Bradley took a huge gamble: He turned down the Khan bout and went to court with his promoters to free himself of them. At the time, public opinion of Bradley dropped precipitously. For many fans, Bradley was a boring, overpaid fighter who had somehow headbutted himself into a fake stardom, and now he was getting called a coward.

By the end of 2011, though, Bradley had wrangled free of his promoters, and enlisted with Top Rank, the promoter that had long been publicly eyeing him as a charismatic, talented but underpromoted fighter. Top Rank not only is a gifted organization when it comes to grassroots promotion, but it also is the promoter of Pacquiao. Top Rank prefers to work in house and not with other promoters, and it was running out of viable in-house opponents for Pacquiao. Bradley could be nurtured for a Pacquiao fight down the line. He was thrown on the undercard of Pacquiao’s last fight, against Juan Manuel Marquez, to whet the appetite for a potential Pac match-up. Top Rank made the ill-advised decision, however, to match Bradley with Joel Casamayor, another head butt-prone fighter, and one who was badly over the hill. The resulting Bradley win whetted nothing.

It’s unclear why Pacquiao settled on Bradley as his immediate next opponent. Top Rank had talked about Bradley as an option down the line, not right away, because it would take a while to build up Bradley’s name. Most likely, the rematch terms Marquez sought were too gaudy, and Marquez — having fought Pacquiao three times, all three times giving Pacquiao fits — was viewed as too dangerous at that price. Once more, Pacquiao and Mayweather couldn’t even come close to agreeing on a fight. That left Bradley as the most viable option. And it will give Bradley a payday that far eclipses the bypassed Khan payday.

Bradley brings a few things to the table, in terms of a salable fight. He speaks English as his first language, an underrated and rare characteristic for Pacquiao opponents over the years. Anyone who’s been watching Bradley on 24/7 has seen an obviously likeable person. He has a bright smile, is “handsome” according to Pacquiao himself, radiates confidence without coming across as arrogant, and talks openly and convincingly about his love of his family (including his father, as well as his wife, with whom he has one child; she also has children by a previous marriage that he speaks fondly of). He says funny things: In one segment, while describing his infant daughter’s tendency to bump her noggin, he quipped, in a self-deprecating play on his reputation for head butts, “She’s got a Bradley head, so I’m not really too worried about it.” My own view of Bradley is that he says what he thinks he’s supposed to say sometimes, like when he used to talk about how Mayweather was better than Pacquiao but changed his tune once he signed up with Top Rank. It’s a minor complaint. He might be a touch manufactured, but it doesn’t veer off into incredible phoniness a la Ortiz.

The back story for Bradley isn’t the usual “holy shit, how’s he still alive” tale, but he also didn’t come up under the best conditions:

The other thing he brings to the table is that he might actually beat Pacquiao, in the estimation of many boxing obververs. The hardcore fans know that Bradley’s style — intelligent, active, hard-nosed — is one that could give Pacquiao trouble. Bradley is good at adapting to his opponents, like Marquez, and Marquez has been a thorn in Pacquiao’s side his whole career. Bradley isn’t as magnificently skilled as Marquez, but he is faster and younger, in his prime at age 28. A big question, one we’ll explore in future blog posts, is whether he’s big enough physically for Pacquiao; at 147 against Abregu, Bradley was a shadow of his 140-pound self, but on 24/7 Bradley really looks like he’s filled into the weight this time.

What Bradley doesn’t bring is the expectation that he will be in an entertaining fight with Pacquiao, because of his tendency to head butt and a reputation for being in unappealing bouts overall.

Nor does he bring a big name. But if he beats Pacquiao, he’ll leave with one.