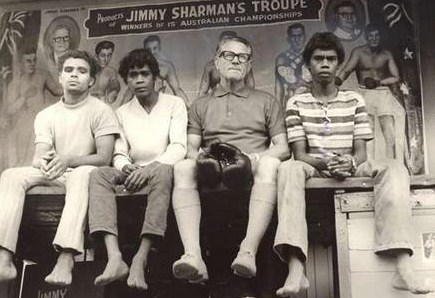

(Tent owner Jimmy Sharman, Jr. with his boxers)

“It was the easiest thing in the world for an Aborigine to get into a boxing troupe. They would grab them before they’d grab a white bloke. They were a drawcard. You know, you see Aboriginals on the Board and then a lot of people would come in to see the Aboriginals fight. You see most of the troupes they all got Aboriginals. They thought they were better fighters and they were wild looking blokes.”

-Henry “Banjo” Clarke, tent boxer at 15

In the country where Jack Johnson became the world’s first black heavyweight champion, aboriginal boxers have always punched above their weight. Emerging from a level of poverty and marginalisation difficult to imagine, the roll call of indigenous champions is impressive: Lionel Rose, Dave Sands and Tony Mundine are just the beginning.

Many aboriginal fighters got their start in boxing tents, sideshow attractions that have crisscrossed the country since the start of the 20th century. The tents had their heyday in the 50s, when entrepreneurs like Jimmy Sharman and Roy Bell and their troupes followed an exhausting calendar of nearly 500 agricultural shows, carnivals and rodeos from Cairns to Melbourne and back.

Fighters would sleep in iron cots on trucks and buses, setting up the ring in the morning and packing it up at night, earning around £1 a day to fight all comers. For aboriginal boxers, that small wage was much more than they could earn working as a stockman or farmhand.

Many just liked the social life. Ray “Muscles” Clarke, a tent boxer in the 50s, said: “We’d drink in their houses and in the pubs. Or go to one of the houses and a girl would say ‘would you like to dance.’” One of those dances must have gone well, because “Muscles” told historian Richard Broome that at one point he considered marrying a white girl he met on the road.

With dates booked a year in advance, towns were plastered with fight posters by the time the troupe rolled into town. After they’d pitched the tent, boxers stood on a platform or “board” outside and waited for a crowd to build. They strutted and posed as the announcer introduced them to the growing throng.

Then it was time for the “gee” to step up. A local employee or a member of the troupe sent to the town in advance, the job of the “gee” was to stage a confrontation, playing on the emotions of the crowd. Two “gees” might start a fight and the promoter would invite them to “step inside and settle things like men.” The “gee” might play the role of the drunken woodcutter picking on the smaller, quieter aboriginal boxer, who, in a reversal of the norm, might find himself with the crowd on his side. Second generation tent boxing promoter Alan Moore told Broome: “We used to have a white guy the bad guy and a little dark bloke the good guy, quiet and unassuming… The crowd loved them, not knowing that it was not true as can be, but very, very entertaining, extremely entertaining.”

Once the match ups had been settled on the “board,” the crowd flowed into the tent. The ring, usually no more than a sawdust floor with hessian sacks for ropes, would host bouts well into the night. The “gee” and his opponent would put on a show, punching with open hands and feigning wobbly knees. The real danger for tent boxers was taking on locals from the crowd. Often drunk, punters fought to be able to say they’d beaten a tent boxer, or an aborigine.

Fighting up to five times a night against men much bigger than them, tent boxers often found that their footwork didn’t count for much in a 22-foot ring covered in deep sawdust. To make matters worse, they were often under orders from the tent boss to lose or take a dive, ensuring that more paying locals would step up later in the night.

With boxers fighting several times a night more than 300 nights a year, the tents were a boxing mill – creating, sustaining and eventually using up thousands of fighters. Many Australian champions got their start in the tents; Aboriginal fighters like Ron Richards, Jack Hassen and George Bracken, alongside white men such as Mickey Miller and Jackie Green. Many continued to travel the country with troupes even after achieving professional success.

Dave Sands, the Empire middleweight champion and #1 contender to Sugar Ray Robinson, could stop traffic in Sydney when he went for a run. Like Joe Louis, Sands, an aboriginal man from Kempsey, New South Wales, achieved popularity that crossed racial boundaries. But despite international success and the adoration of many Australians, Sands still plied his trade in the tents until his death in a truck accident at age 26.

Most Australian states introduced new, stricter boxing regulation in the early seventies, sounding the death knell for the tent boxing circuit. Today only a few troupes survive, travelling the dusty outback roads of Queensland and the Northern Territory. The boxers, in the main, are still aboriginal and the pay still isn’t great. But at the end of the world, in Birdsville or Alice Springs, you can still lace up the gloves for a couple of dollars and step on to the sawdust with a professional boxer.

Special thanks to Axel Williams for help researching this piece.