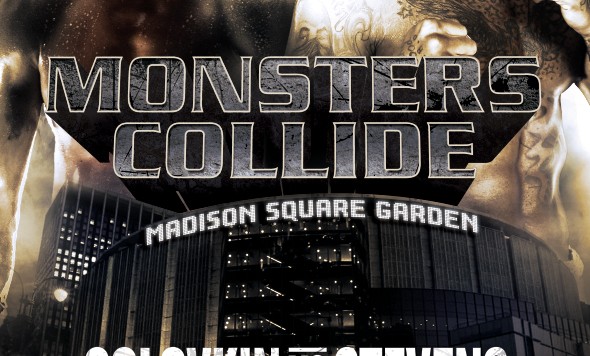

Whether it’s Russian roulette or an old-fashioned drinking contest, play any game where the central element is powerful shots and sooner or later, someone’s going down. Saturday’s showdown on HBO between middleweight knockout artists Gennady Golovkin and Curtis Stevens is far closer to the Russian roulette end of scale, which is to say that the end will come sooner than a wear ’em down evening of endurance drinking.

Golovkin is one of the key pieces in HBO’s play to fend off insurgent Showtime, and the reason is obvious to anyone who watches him for a few minutes: He is frightening in all the right ways. If you’re going on the merit of his wins, Stevens has done nothing to earn a meeting with Golovkin. Instead, he sold enough people on the match-up by way of a few showy knockouts of his own, with a typically crafty rebuild job by promoter Main Events, by being one of the few boxers who wanted it (Golovkin’s risk/reward ratio is improving, but he’s still more risk than reward) and by talking trash on Twitter. We end up with a situation where, to paraphrase Andrew Fruman, Stevens will not be the best opponent of Golovkin’s career but he will be the most dangerous.

That’s because we do not know yet just how well Golovkin can take a shot. We know he can take one at least pretty well — Gregorz Proksa had scored a sensational knockout or two prior to their meeting, and when Proksa hit the man known as GGG he didn’t flinch. But Stevens has nastier stuff than Proksa. Here’s how nasty, if you assume this isn’t a bit of gamesmanship from HBO to promote an opponent for Golovkin that some fans don’t buy as worthy: Network commentator Max Kellerman recently said that, during beta testing for a new technology to measure the punching power of boxers, Stevens’ levels were so unbelievable that some at HBO weren’t convinced the technology worked.

Stevens’ nasty stuff has been made all the nastier by a move down from super middle to middle. He always has had power, as part of a youth movement out of New York known as the “Chin Checkers,” but he wasn’t cremating guys at 168 like he has been at 160. Now, some of that probably has something to do with careful matchmaking from Main Events, who are good at taking boxers out of the scrapheap and putting them in with opponents who make them look good. Sometimes the rebuild is authentic; it takes. Sometimes it’s an illusion; it vanishes the moment it’s subjected to any scrutiny. What I do know is that I’ve never seen Saul Roman, Stevens’ last victim, dispensed with so quickly and so thoroughly.

That weight shift has helped sell Stevens as a new man, but it also was probably the right move. We haven’t seen Stevens wobbled or dropped as he sometimes was in his previous division, so maybe he handles the punches better here. He was short for a super middleweight and in fact is still short for a middleweight, 5’7″. But his opponents are closer in stature than before. Size is only one of his numerous flaws: He’s lazy on defense, tending to drop his gloves for no reason. He doesn’t respond well to pressure, something Jesse Brinkley showed at 168 but that Derrick Findley also showed at 160. He can counter some, because he’s fast enough (certainly faster than GGG), but for some reason despite that ability, if you back him up he looks lost. Ultimately, his power in both hands — right cross, most especially the left hook — has made up enough for his flaws to get him to a big fight. He was once banished from the big networks for the awful Andre Dirrell bout, and once suffered the ignominy of being outboxed by Brinkley. But power has a tendency to intoxicate.

He’s an underdog, deservedly, because GGG does everything better, technically. He’s slower, certainly. For all his hype, his resume is not overloaded — although Proksa, Matthew Macklin and Gabriel Rosado are worlds better than anything Stevens has going for him. Neither man is a defensive master, but Golovkin has the edge and showed improvement against Macklin. He’s comfortable leading or countering. He adjusts on the fly. He has power in both hands, too. He’s a better body puncher. He’s not shown any of Stevens’ trouble when getting hit cleanly. There’s a class gap, really.

Where there might not be a gap is in power, and that’s why Stevens is live. The usually dispassionate GGG — except for that creepy, childlike grin he flashes occasionally, he’s most often got a calm expression across his visage no matter what happens — has admitted to having his feathers ruffled over some of Stevens’ antics, such as the images he posted on Twitter of a mock funeral for Golovkin. If Golovkin comes in reckless, Stevens’ chances increase.

I still don’t like those chances under any scenario. I won’t at all discount Stevens’ chances of winning because he hits hard enough that it might come down to who lands the first clean punch. But in a duel between two deadly shooters, I’m going to take the cowboy with the better aim over the one who draws faster. Golovkin by early knockout — it goes three or fewer, perhaps even just one.