Spoiling has stumbled back into fashion of late. After Cuban cephalopod Richard Abril put the dampeners on Ugandan Sharif Bogere within hours of England’s Matthew Hatton and South African Chris van Heerden hugging one another to professional death, fight fans were left to pine after a performance that might clear the airways. Unfortunately, the stink left over from Abril and co. lingered into an additional week after Bernard Hopkins nullified another unbeaten patsy with his efficacious brand of marring.

Fighting ugly is no sin — at least not for its practitioners. In boxing — perhaps more so than in any other sport — a winning record can generate hot money whether achieved through excessive clinching, uncomely pacifism or ungallant conduct. Here follows a handful of boxers that were adept at it — that could spoil, maul or flat out bore as well as anyone in history.

Saoul Mamby

“Sweet” Saoul, a Jheri curl-sporting Jew from the South Bronx, carped of a bloodlust inherent in the American fight crowd, and if anyone was well-placed to contrast international viewing habits then it was the cosmopolitan operator Mamby. A superbly conditioned Vietnam veteran from Spanish-Jamaican descent, he sought his fortune across the globe in an astonishing 39-year career — racking up wins in Jamaica, Zambia, Quebec, Seoul and Paris.

An attraction at New York’s Felt Forum back in the early 70s, Mamby’s expert technique and nimble brain allowed him to control the pace and rhythm of a bout. He could buffer things down to a crawl when the need came, and mess a man up inside as required. And rarely was he hit.

He matched wits with the likes of Roberto Duran, Edwin Viruet, Buddy McGirt, Billy Costello, Antonio Cervantes, Maurice Blocker and Esteban De Jesus — names from cojoining eras — in 85 contests that returned him a version of the super lightweight world championship when he starched South Korea’s Sang-Hung Kim in February 1980.

Sammy Angott

Samuel Engotti, the former lightweight king from Washington, Pennsylvania, was known as “The Clutch” based on his penchant for swaddling opponents after launching an attack. Stout, pugnacious and wild in the clinches, Angott made good men look plain.

A marauding tangle weed that burrowed in with his head, Angott grappled his way to the world title when he mugged Texan “Looney” Lew Jenkins in 1941. Hand problems clipped short his tenure, yet only 4 months after he had been forced to abdicate from an 11 month reign, Angott rebounded to blot the copybook of one Willie Pep, then 62-0. An expert at crowding and mauling, he harassed Pep like a street corner pitchman.

Sammy went down thrice to Sugar Ray Robinson, in scuffles that resembled a man attempting to flush a spider down a sink hole, but his approach fared him better in wins over Bob “Bobcat” Montgomery, Baby Arizmendi and Ike Willams. Angott retired to Masillion, Ohio, where he worked in the shipping department at the Yale, Towne and Eaton Manufacturing Co.

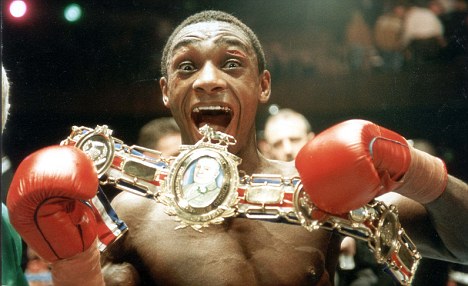

Herol Graham

Marvelous Marvin Hagler didn’t see any good sense in mixing with Graham – nor did Thomas Hearns or Nigel Benn. Alan Minter — the Crawley bleeder that Hagler cleaved the middleweight championship away from — dismissed Herol from training camp after he was unable to hit him. Chris Eubank admitted recently that he landed on Graham only once throughout a fortnight of sparring that bordered on degradation.

He was the archetype for the Brendan Ingle-inspired rubber men that came to revolutionise boxing in England’s Steel City. Gently-spoken and mild-mannered, the Nottingham-born southpaw of Caribbean origin became a muse for tearaways such as Johnny Nelson, Naseem Hamed, and Junior Witter — kids groomed in his image and taught to emulate his chic. The eccentric Ingle would flash “The Bomber’s” will-o’-the-wisp routine in so-called exhibitions held amid smoke-filled Sheffield social clubs that amounted to little more than Graham tormenting have-a-go drunks with his hands held behind his back.

For all of his magic — and there was plenty — he fell agonisingly short against Sumbu Kalambay, Mike McCallum and Julian Jackson.

Fritzie Zivic

Ferdinand Henry John Zivicic aka “The Croat Comet” learned how to disable a man while keeping order in his father’s saloon. A conniving roughhouse from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Zivic bludgeoned the great Henry Armstrong to defeat in 15 foul-infested rounds to ascend the welterweight summit in the autumn of 1940.

If Mamby and Graham were cute, Zivic was their antithesis. Flat-nosed and lantern-jawed, Fritzie was proficient in the dark arts. As neat with his head, his thumbs or the heel of his glove as he was at bowling one in beneath the beltline, Sugar Ray Robinson remarked that he learned more from Zivic than anyone else.

There are few that have faced a better roster: Jake LaMotta, Charley Burley, Kid Azteca, Bob Montgomery, Beau Jack, Lou Ambers, Freddie Cochrane, Lew Jenkins, Izzy Jannazzo, Phil Furr, Bummy Davis and Jimmy Leto were all accommodated (along with the aforementioned trio of Robinson, Armstrong and Angott). Zivic beat some, lost the others but fought like the devil regardless. After hanging up his gloves in 1949, he settled into his second life as a boilermaker.

Jimmy Young

Philadelphian Young is remembered for banishing the original George Foreman to the margins, after he befuddled the ogre-like ex-champion into an epiphany in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1977. A back-pedalling survivalist, he was a conscientious objector during a war plagued era.

Sniping hither and thither, Young used his quick fists to score points and stay safe — think Wladimir Klitschko in the body of Eddie Chambers. His approach cost him contentious verdicts against Muhammad Ali and Ken Norton but was enough to see off the malevolent Ron Lyle twice.

The Ali and Norton snubs cut him deep; of his remaining 26 contests he would lose more than he won. His spirit, melancholy and bruised, withered. The 80s Lost Generation used up what was left of the fighter. Broke and flitting between menial jobs in his ramshackle blue Cadillac, he sought solace in predictable ways to make oneself vanish. In a cruel irony, the mind that once let him creep through a thunder storm; the one he so strived to protect, crumbled also. His heart, long since tattered, surrendered on 20th February, 2005. He was 56.