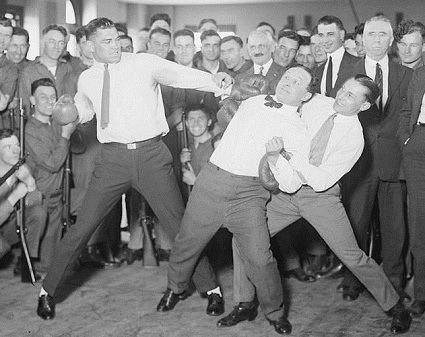

(Jack Dempsey, left, pretends to punch Harry Houdini, with Benny Leonard’s help)

There exists an adage in boxing: “As the heavyweights go, so goes boxing.” It’s a fancy way of saying that most people extract more pleasure out of the sport the larger the fighters are, and the harder they’re hitting each other. It also means that the smaller a fighter is, the more difficult it will be to swat a path into public consciousness.

Times have changed, needless to say, but though the popularity of heavyweights has waned in recent years, the little scrappers still find it difficult to earn top billing.

Many boxing fans are either too young to remember but for eras on end the heavyweight champion was not only the proverbial “baddest man on the planet,” but he was often among the most famous or easily identified. It was rare indeed that a smaller fighter could step into that world of celebrity.

On May 28, 1917, “The Ghetto Wizard” Benny Leonard took a huge step toward achieving exactly that.

When fighting once per month is not only common, but expected, fighters learn how to eat losses and move on. Mickey Finnegan, an unheralded 1-1 (1 KO) fighter, knew about that and taught it to Leonard in his professional debut with a TKO victory in three rounds over the future legend.

Before one year had gone by, Leonard had three more stoppage losses under his belt. Then the bustling New York fight scene hardened the maturing fighter, turning him into the man that only lost to Johnny Dundee, Freddie Welsh and Johnny Kilbane — all greats in their own right.

In two prior fights against Welsh, Leonard couldn’t find a clear, title-winning victory over the aptly named Welshman. However The Repository, among other publications, referred to Leonard as not only the best lightweight in the world (despite his lack of a title), but the “American lightweight title-holder.” He had proven himself a worthy, improved fighter and now he needed the hardware to back the claim up.

In a land of endless veterans, Welsh was indeed experienced, but long in the tooth. With over 150 bouts on his ledger, ring wear and tear had begun to clearly slow “The Welsh Wizard” down, and he went into the fight having lost newspaper decisions in his previous three bouts, including one apiece to Rocky Kansas and Kilbane.

Losses to the upper echelon weren’t the issue, though. Defeats and near-defeats to relative novices Richie Mitchell, Buck Fleming and Eddie Wallace just few fights earlier were.

Stateside, few publications seemed keen on either picking Welsh to best Leonard or rooting for him to do so. For instance, The Oregonian bemoaned Welsh’s style: “The studied clinching of the Briton is all that enables him to obstruct the wheels of progress and cling to the lightweight title long after he has ceased to be the best man of his class.”

The Watertown Daily Times also beamed about Leonard before the fight, reporting, “[Leonard’s] punch is no fluke. It carries sleeping potion with it, and Leonard can put it over in a flash. Crafty as Welsh is, he will find Leonard on top of him in their coming battle, seeking the one chance to land. If Welsh fights he will be in more danger than if he uses his pet stalling tactics, and because Leonard is clever, because he has mastered ringcraft, there are some who believe he will knock Welsh out.”

To make oddsmaking matters worse, after having beaten Welsh in early May, Kilbane said, “Eventually the lightweight title will be turned over to Benny Leonard, I believe, and if such will be the case, I will take Leonard on, for I know I can beat him.”

Betting odds out of New York had Leonard a 7-to-5 favorite to win on points, and a 5-to-9 that Leonard would win by stoppage.

There was a last minute wrangle over the appointment of Billy Roche as referee, as Leonard’s manager Billy Gibson protested the decision. Roche had been involved in Welsh’s defense over Charley White at the Ramona Athletic Club in Colorado Springs, which saw a large section of the makeshift arena fail, killing two spectators and injuring hundreds. Moving past the horror, the two men fought, with White getting the better of the action according to most, yet Roche awarded the decision to Welsh. Instead both parties compromised, choosing former lightweight title challenger Kid McPartland.

Using savvy and occasional awkwardness, Welsh began well in round 1, keeping the charging Leonard at a distance before being forced to go defensive in rounds 2 and 3. Rather than his usual clinching and turning, Welsh put on an impressive display of blocking and parrying for sequences at a time, but couldn’t much offensive momentum.

His right hand always at the ready, Leonard used his left to work his way in and continue being the aggressor. Welsh found moments to strike back in the middle rounds, pushing Leonard back briefly before being overwhelmed by the younger, stronger man. The combination of being endlessly stung and frustrated gnawed at whatever shell Welsh had left until Leonard saw his opportunity and took it.

United Press correspondent H.C. Hamilton described round 9 as such: “The ninth round was furiously fast, when Leonard started the whirlwind that brought the old champion down. Welsh started into a clinch. Using his right hand almost for the first time in the bout, Leonard crossed behind the champion’s guard. Welsh ducked, but he was too late. The smashing power of the mauling fist caught him on the temple. Welsh tried vainly to stagger into a clinch. Leonard slipped away and his left crushed square onto Welsh’s chin. Welsh sagged until his knees touched the floor. He finally went down, one hand clinging to the ropes in Leonard’s corner. He arose, both hands on the ropes, his head unprotected. A dozen times the flailing fists of the eager challenger crashed into Welsh’s chin. Gamely the Britisher stood it. Kid McPartland, the referee, looked appealingly to Welsh’s corner, but the sponge was not forthcoming. McPartland mercifully stepped in and ended it.”

Welsh found himself caught in the ropes and nearly unconscious and a sea of people flooded the ring, celebrating their newly-crowned American lightweight champion.

“I felt in my heart I would be the lightweight champion tonight,” said Leonard afterwards. “I never lost that conviction. I am happy beyond words that I have brought the lightweight title back to America. I want to pay tribute to Welsh. He is a good, game fellow, and I am only sorry that I had to climb over him to victory.”

A disappointed Welsh said during his post-fight interview, “I protest the action of the referee as I feel that I did not get a fair deal. There never was a championship decided without a man getting a count.”

It would be Welsh’s last fight for over three years, and he would only fight six times more, going 4-1-1 (3 KO). At 31 and a lightweight, his career was all but over going into the fight, yet he found a way to make it a difficult one anyway.

In the mark of a true crossroads encounter, Leonard announced immediately after the bout that he would enlist in the U.S. Army following his next fight. He followed through, becoming a boxing and close combat fighting instructor, but boxed exhibitions and pro bouts to benefit different armed services funds during U.S. involvement in World War I.

Leonard would stay unbeaten until 1922, save for a newspaper defeat in four rounds to Willie Ritchie, and rise to be a national hero to many, and holds a special place in Jewish boxing history. To date, he remains one of the best lightweights ever.