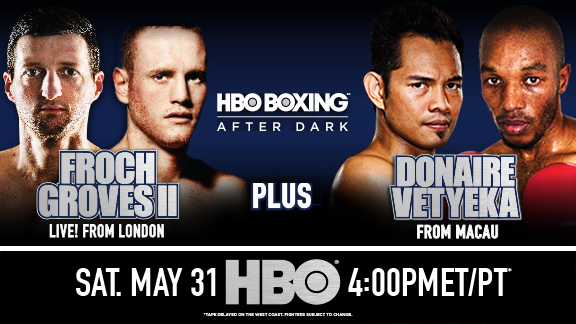

This is how chock full of boxing this weekend is: One of the best 10 or 15 fighters alive — from one of the most boxing-mad countries on the planet — is fighting Saturday on HBO against perhaps the #1 fighter in his division, and it’s been overshadowed by Carl Froch vs. George Groves II to the point of total eclipse.

Nonito Donaire has himself to blame for some of this, some for his choice of opponent, and some of it is not his fault at all, because Froch-Groves II is about as enormous as a boxing match can get on the globe. On another weekend, however, it would get more of the spotlight it deserves. Donaire is a featherweight these days, a division that even with mega-star wattage tends to suffer from “I was that size as a sophomore in high school” syndrome. Yet Donaire has a way of undershooting the hype his talent warrants, having burst onto the scene with Knockout of the Year-style KOs against Vic Darchinyan and Fernando Montiel but tending toward ho-hum performances between the kind that are absolutely exhilarating, and sometimes (as with the Darchinyan rematch) alternating mid-bout from one to the next. He has, candidly and to his credit, admitted struggling with motivation. For a 126-pound man who has made significant cash and has a family to tend to, is it so crazy that he might want to find a way to avoid getting punched in the face for a living? It’s just not a great sign, is it?

All of this and more is why Simpiwe Vetyeka has a terrific shot of beating Donaire Saturday in Macau, China. Vetyeka, a South African, has fought nowhere near U.S. television or soil. He spent all of 2013 conquering the island nation of Indonesia, first beating fringe contender Daud Yordan and then toppling featherweight kingpin Chris John. He now moves to conquer America, by way of Donaire, whose family hails from another Asian island nation, the Philippines. That Vetyeka is relatively unknown in the United States partially accounts for the low profile of Donaire-Vetyeka, but make no mistake, Vetyeka is an earnest threat to Donaire’s waning pound-for-pound status. He is a true featherweight in a division where Donaire has only been tested against an inflated would-be contender in Darchinyan, and Vetyeka is a rough, awkward customer like Darchinyan himself. Plus, Vetyeka has a hunger that compensates for his weaknesses; he was motivated in his upset of John by the demise of Nelson Mandela, and is motivated now by a desire to prove he belongs against Donaire.

Donaire, even in his flyweight days, never had the body of a chiseled specimen. Rather, he has always bore the physique of a teenager who has a little fat on his frame simply by the virtue of his youth. Yet as he moves up in weight, from 112 to 126 now, he has acquired more unnecessary flesh, and each new divisional leap has diminished his power. Oh, it remains at 126, as the 9th round crushing of Darchinyan showed. But it is still untested in full at featherweight. His speed and reflexes, too, are not as inhuman as they once were, and he no longer towers over the competition. At 5’5 1/2″, he is shorter than Vetyeka at 5’7″. Still, watching the 9th round of Donaire-Darchinyan II, it’s hard not to see glimpses of the man who once captivated the sport with his raw talent.

You can pinpoint the start of Donaire’s decline to his arrival at the peak of the sport as boxing’s 2012 Fighter of the Year. That he ran into Guillermo Rigondeaux in 2013 explains much about the start of his down year. So, too, does how he essentially trained by phone for that bout with Robert Garcia. For the Darchinyan rematch following the Donaire loss, Garcia also was not fully engaged, as Donaire brought in his father again after a long separation. Now, Garcia is marginalized to the point of sitting in Donaire’s vicinity for this fight, willing to provide advice as needed to the Donaire father/son team. Donaire has sold the reunion as a sign of his renewed dedication, but this is now the third consecutive fight where he is selling the message that he is not a Fighter In Name Only. Donaire’s physical abilities are such that he can beat quality fighters simply on the strength of that. By contrast, quality fighters who aren’t nearly in Donaire’s league physically also have a chance of beating him simply because they’re the ones really trying.

Enter Vetyeka, who has apparently permanently escaped the status of also-ran (he lost definitively to much-acclaimed Hozumi Hasegawa in 2007) to arrive at full contender status. He has done so with typically African toughness and atypical Boxing awkwardness. Vetyeka was aggressive against Yordan and especially aggressive against John, stopping both of them. He has never been hurt that I’ve seen, and all the while that anyone is trying, he’s hitting them with oddball punches while skittering around in unpredictable directions. He fights with his hands down, a la a less elegant Roy Jones, Jr., which makes him hittable but also means his hands are coming from peculiar angles. He’s capable of throwing an arrow-straight jab upstairs and downstairs, but a great deal of what he does is ragged — his lefts and rights to the body, his counter rights, his lead right uppercuts. He will switch stances from orthodox to southpaw like he doesn’t know he just did it, and alternate the pattern in which he’s circling at random intervals. He can punch, even if he is not ultra-powerful, and his speed is not elite, although his feet are more fleet than they might initially appear and his periodic straight punches are (duh) faster than the crooked ones.

The best way to fight Vetyeka probably is to swarm him, something Donaire won’t do. Vetyeka would rather swarm his opponent, something Donaire tends to enjoy, given his gift for the knockout counter left. The question, then, becomes whether Vetyeka can find a middle ground of intelligent, awkward pressure that equals that of Darchinyan’s in the Donaire rematch while withstanding the worst of Donaire’s speedy, powerful counters. On years of elite experience practicing awkwardness, Darchinyan certainly has Vetyeka beat. But Vetyeka is significantly bigger than Darchinyan, with no signs prior of being hurt like Darchinyan has at weight classes at or below 126.

Assuming all of that comes into play, Donaire would need to have found his boxing soul again in preparation for this fight, something that he has not obviously done — he has, rather, been searching for it for some time. Or, perhaps, he can get lucky with the Macau crowd cheering him on and win a close battle on the cards. Here’s what’s easier for me to imagine: Donaire, accustomed so long to using his height and length to dominate smaller fighters, finally runs into a naturally bigger man who’s a bridge too far; a naturally bigger man, by the way, who doesn’t go down when Donaire hits him with his best shot, and steadily applies his herky-jerky intensity on the guy who has already “made it,” thereby out-hustling and mauling Donaire to take a close decision that’s closer on the scorecards than it is in reality. Donaire might again hang on to his elite status by the hair of his chinny-chin-chin. But barring a total rebirth, look for that goatee to get snipped once and for all.