“His very existence was improbable, inexplicable, and altogether bewildering… It was inconceivable how he had existed, how he had succeeded in getting so far, how he had managed to remain — why he did not instantly disappear.” – Joseph Conrad.

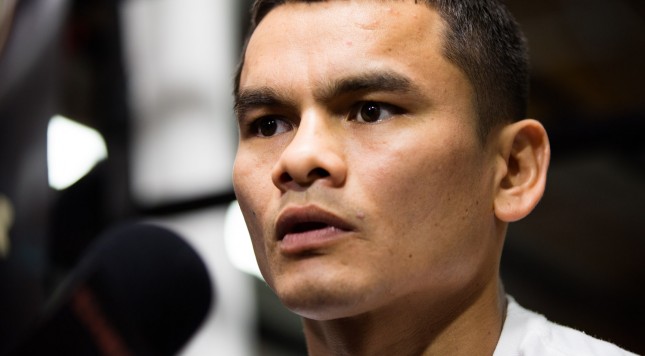

If the trappings of fame and a now-global renown have changed Marcos Maidana at all, he doesn’t let it show, save for the odd sartorial flourish. I don’t mean in terms of mink coats and jewellery — I doubt such trinkets would go down well in rural Santa Fé — but rather the foppish pair of Ray-Bans he’s taken to wearing in recent months. They sit awkwardly across his squashed nose and hint at compromise, at an attempt to soften his harsh, unflinching features and remind the world that he is a human being as well as a fighter of the most bloody-minded disposition.

To the overzealous PR man, Maidana is the unruly gaucho set to give Floyd Mayweather the toughest night of his life. In more poetic terms, he is the other made flesh, defined by an absence and the binary relationship with the house fighter. Boxing, due in part to both the fundamental nature of the sport itself and the unevenness of its playing field, best exemplifies this oppositional play.

We are necessarily faced with two sides, of which one is looked upon favourably due to a myriad of potential factors, from the location of the bout or the prominence of the management, to the nationality of the judges or the whims of the local audience. The other, as they say, is there to give it his best shot.

It’s a worrying sign of just how much editorial control Floyd Mayweather wields at Showtime that the latest episode of All Access portrayed his gym — “The Dog House” — as precisely the type of chaotic bullpen that would have once spawned a fighter like Chino Maidana. Having built his name on exhaustive preparation, Floyd’s decision to paint himself as the product of some fevered street fighting bunker was as transparent and contrived as Leonard Ellerbe’s resumé.

Mayweather, and indeed the broader Money Team stable, don’t do underdogs. Regardless of what skills they actually possess, they will always be the ones with red carpet underfoot, as liable to receive a long count as to secure the lion’s share of the purse. Yet by definition, the A-side fighter exists only in opposition to the man facing him. Without another world to conquer, he is meaningless. He has the name, the record, the skills, and the perceived pedigree that his opponent does not, but to claim that he does not need him would be entirely false. His achievements, after all, are given resonance only by their absence in the men he faces; they serve to set him apart from something or someone else.

To this end, Floyd portrays himself as a man alone, an island who has reached such rarified heights that the rules need no longer apply. He “transcends the sport,” as his team so loves to say. And in many ways they’re right. But even the finest of his generation must subscribe to the binary laws that govern the game, those which state that, prior to the contracts being signed, the A-side is simply a succession of press releases, that only once an opponent is in place can he begin to fulfil what was promised. The reinforcement of difference, of otherness and absence in the opposing figure is what keeps the chosen one at the top. It defines both the red and blue corners. It is a contradictory yet precise source of chaos and order.

Crucially, then, for every Floyd Mayweather destined for greatness, there is a swarthy other groomed to lose the big one, to come up short when it matters most and offer a potent reinforcement of their opponent’s allure.

Fighters from this sub-section, unique in many ways, are no less prepped than their star-spangled cousins. They are also brought along carefully, with the intention of getting sufficient experience and a taste of victory to justify their entry into the upper pool, however fleeting this may prove to be. They may exist to prop up something greater, but they should never be overlooked, as without them the structure of the sport would rapidly shift from merely unstable to certifiably condemned.

Victor Ortiz was once that A-side. So, too, were Amir Khan, Andriy Kotelnik, Devon Alexander, Adrien Broner, and Floyd Mayweather the first time around. Whether or not Maidana overcame the restrictions of his role — and he beat enough of those guys to stay, if not front, then certainly centre — he was always the supporting cast member, the jobbing actor brought in to react and marvel as the soliloquies were rattled off by the star. That he chomped through the scenery is why he’s here today. And more importantly, it’s why he might just reverse the equation.

(Photo: Stephanie Trapp, Showtime)