“War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.” – On War, Carl von Clausewitz

One of the more notable warriors in the sport of boxing, Matthew Saad Muhammad, had but one will when stepping through the ropes: lay waste to whatever was standing across from him at the opening bell.

Not exactly a shrinking violet himself, Alvaro “Yaqui” Lopez nonetheless wasn’t the same type of destroyer that Saad Muhammad savored being. But what he lacked in any department, he made up for with a grinding tenacity, will, and surreal toughness.

And in a sport where hyperbole and bluster often give way to the reality that getting punched doesn’t feel good, true, unwavering warriors are deservedly celebrated. Rarer still is the ability to bang a sizable dent into the fabric of a truly great era of fighters by way of unforgettable smash-up.

These men did it twice, making a fraction of what many fighters today take home.

Saad Muhammad was no stranger to trouble. He knew homelessness, and had recently become a spokesperson for addressing Philadelphia’s homeless issues. Boxing historian Henry Hascup reported on Facebook that, according to Saad Muhammad’s long time friend Mustafa Ameen, the former light heavyweight titlist passed away on Sunday at Chestnut Hill Hospital in Philadelphia, Penn.

Boxing lost a warrior.

*******

The hardship Saad Muhammad faced fit firmly with the Philly fighter archetype, though his hardship was unique, and memorable.

Born Maxwell Antonio Loach, his mother passed away when he was a baby, leaving him and his brother in the care of an aunt. The aunt, no longer able to support the two children together, ordered the elder brother to take three-year-old Maxwell for a walk and abandon him.

A police officer came across the young boy on the famed Benjamin Franklin Parkway, not far from where Sylvester Stallone ran the “Rocky Steps” out the front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Maxwell was taken to a Catholic orphanage, where he was misunderstood when asked his name. The nuns running the orphanage renamed him Matthew Franklin, after the saint and where he was found, respectively.

Franklin waded in and out of reform schools before being adopted. Understandably, he was a vexed youth who expressed himself with his hands often. Being small of stature and losing fights on his way to school, Franklin wandered into the Jupiter Gym in South Philly as a 15-years-old. When he eventually began to fight competitively, he ended up with a reported amateur record of 25-4.

Franklin still managed to find time for trouble, though; by the age of 17 he had been arrested three times for “gang activity.”

Inspired by seeing Muhammad Ali spar in a Philadelphia gym, Franklin made the choice to become a full-time professional fighter when he was 20, perhaps also as a way to stay out of trouble — relatively speaking.

He debuted at the now-demolished Spectrum, a boxing landmark in the “City of Brotherly Love.” Earning a knockout in two rounds over Billy Early, an instant addiction to the roar of the crowd dug its talons into Franklin.

In his first 11 bouts, he fought seven times at the Spectrum, once in France, going 9-1-1 (7 KO), with both blemishes being against unknown Wayne McGee.

The next six fights spanned just under a year, and were against the likes of future light heavyweight titlists Marvin Camel and Mate Parlov, two times apiece.

In May of 1976, Franklin spotted Olympic gold medalist Parlov five pounds in Italy, then earned a unanimous decision. Two months later, Franklin pounded out a decision over Camel in Stockton, Calif., but subsequently lost a rematch in Montana. A wire report out of Helena a few days later stated, “The Montana Board of Athletics ruled Monday that a split decision by light heavyweight fighter Marvin Camel of Missoula, Mont. would stand as a victory of Matt Franklin. The outcome of the 10-round bout Saturday night in Missoula was clouded when Franklin’s manager, Frank Gelb, tried to inspect the scoresheets and discovered that no one from the Athletic Board was left in the building.”

Franklin then fought to a draw with Parlov, again in Italy, a mishap he would call a “hometown decision.”

In March of 1977, Franklin faced a former New York middleweight named Eddie Gregory (who would later become Eddie Mustafa Muhammad) as the televised support for a Vito Antuofermo vs. Eugene “Cyclone” Hart main event on ABC’s Friday Night Fights. Gregory hussled at Gleason’s Gym in Brooklyn and was trained by Chickie Ferrara, then a famous boxing figure in New York. Gregory frequently scrapped in Philly, however.

Franklin’s revered violent inclination was not fully developed, as he frequently boxed and countered well from a distance behind a bruising jab, but still clearly had punching power to spend.

Pre-fight buildup involved plenty of jabbering, Franklin missed weight by a pound on his initial try, and the in-ring staredown where both men stood brow to brow made the crowd of a few thousand restless.

Gregory walked into a chopping right hand that decked him in the 1st round, but he hopped up, unfazed, and pursued Franklin around the ring. Franklin looked wobbly from a left hook in the 4th, but survived the round. Gregory continued to give chase, occasionally stunning the younger Franklin and eventually hurting him considerably in the last round.

The 10-round split decision loss to Gregory flipped some sort of wonderful switch in Franklin’s head, and his boxer/counter-puncher style became much more aggressive.

Two more wins against Joe Maye and Ed Turner brought Franklin’s record to 15-2-2 (9 KO), and set him up for an alley fight against unbeaten former Olympian Marvin Johnson in July, 1977. The bout was for the NABF light heavyweight belt, and was televised on regional network PRISM, which often broadcast sporting events from the Spectrum.

The extremely memorable fight was a bloody mess, with Franklin hurt several times before surging back, trading rounds back and forth, and then some. Much of the fight was fought against the ropes — a display of in-fighting not often seen today — and the it remained competitive up to the later rounds. With both men going past 10 for the first time, Franklin hurt Johnson badly towards the end of the 11th and finished the job in the 12th.

Both men earned a mere $2,500.

The classic bout also served as the beginning of Franklin’s “Miracle Matt” (as he would later be known) reputation, and he became a pugilistic spokesperson at the Spectrum, and a fine one at that.

Just a month and a half after warring with Marvin Johnson, Franklin and Ohio-based Billy Douglas beat the snot out of each other in front of over 7,000 spectators, with Franklin seeing canvas in the 5th before getting a supposedly quick stoppage the following round.

The same day, a fighter named Alvaro “Yaqui” Lopez controversially lost his second crack at a belt thousands of miles away, against Victor Galindez in Rome.

A month and a half later, Franklin floored Dave Lee Royster six times en route to a decision win. Three months after that, he was smashed down with a right hand from Richie Kates, only to wake up and clobber Kates to get the stoppage in the same 6th round.

It was the perfect time to be a boxing fan in Philadelphia.

Franklin overwhelmed both Dale Grant and Fred Bright in the summer of 1978, which lined him up to defend his NABF title for the third time against hard-luck former title challenger “Yaqui” Lopez in October 1978.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vEshNG0s5SA

*******

As a kid raised in an adobe garage in Zacatecas, ZT, Mexico, Lopez used to sneak into bullfights and longed to one day become a matador. His mother kept her aims low, telling him she only hoped he wouldn’t become a criminal.

At 12-years-old, Lopez ditched school to attend the bullfights and finally fight one himself. He was gored through his ankle, however, which left it broken and effectively ended his dream.

Shortly thereafter his parents brought him to Stockton, Calif. to work with them, where the family got by picking onions, cherries, peaches and tomatoes seasonally. Lopez began attending school, but dropped out before finishing 10th grade and began working at a cannery and in local fruit fields.

Lopez, not entirely content relegated to being an anonymous laborer, met his future wife Beatrice while dropping off a friend at her house. After introducing himself, Lopez learned Beatrice’s father Jack Cruz was a boxing promoter in and around Stockton.

Lopez begged his new love interest to introduce the two, and when she finally did so, Lopez asked Cruz to teach him how to fight.

His first amateur fight came against a veteran opponent on a nearby Indian reservation. When one of the event’s promoters asked Cruz what tribe Lopez belonged to, Cruz replied “Yaqui.” And the name stuck.

Lopez wasn’t much of an amateur fighter and only had 16 official bouts. But he did participate in many more unsanctioned amateur smokers at a local prison, where Cruz would take Lopez to get experience.

In April 1972, Lopez turned professional with a six round points win over Herman Hampton in Stockton, and went 3-0 (2 KO) in his first few.

But facing tough Jesse Burnett in his fourth pro fight taught Lopez a lesson in conditioning, as Burnett won a decision when Lopez tired severely down the eight round stretch. Lopez began taking his conditioning training more seriously after the loss, adding rigorous roadwork to his routine.

The next two years saw “Yaqui” move to 20-2 (12 KO), sticking generally to the West Coast. A match-up with the scrappy Al Bolden produced Lopez’s second loss, which was avenged in a rematch in Portland where both fighters went down three times each and each made an extra $750 from cash thrown into the ring.

Lopez also stopped former title challenger Andy Kendall, who happened to be ranked number four in the world at the time, and the Mexican was finely honing his body punching skills.

“Yaqui” made the rounds at a lower level of a light heavyweight division, the tiers and echelons of which were very deep at the time. Lopez knocked Mike Quarry down in the 6th with a left hook before winning a decision over 10; he stopped veteran stylist Bobby Rascon; and he fought Jesse Burnett two more times, going 1-1 and settling on a record of 31-3 (17 KO). In doing so, he was pegged with a reputation for being a hard-charging, tough grinder with a nasty body assault.

In October 1976, Lopez flew to Copenhagen, Denmark, three days before his scheduled bout against WBC light heavyweight belt holder John Conteh. In addition to arriving in Denmark far later than intended, Lopez’ airline supposedly lost his luggage, including training equipment such as running shoes and gloves, which had to be quickly replaced. On top of it all, it was the third time the bout was supposed to have come off, this time being the charm. It wasn’t without major drama, though.

The bout had most recently been delayed by a broken hand suffered by Conteh, but he had also had to postpone due to lawsuits filed by Ugandan president Idi Amin, who had fronted Conteh $75,000 in exchange for holding the bout in Uganda. When the venue was switched to Denmark, the mercurial ruler sued. Additionally, before the bout, Lopez’s promised $25,000 couldn’t be found, and the fight was almost jettisoned on the day, but was eventually salvaged.

In the ring, Lopez gave Conteh issues despite claiming that he was being headbutted too much in close. It became apparent that Lopez was actually at another disadvantage: upon decking Conteh with a body shot, referee Rudolf Drust helped the Brit up and administered an illegal standing eight count, said Cruz. Conteh barely used his frequently broken right hand, but he later said that it held up fine to the punishment.

At the end of the day, Lopez lost his first attempt to snatch a title by unanimous decision, but he was back in the ring in 39 days.

Less than six months later, in April 1977, Lopez was clearly headbutted by Lonnie Bennett and a cut opened up over his eye in a fight he was winning big. Instead of being ruled a No Contest or No Decision, Bennett was somehow ruled the winner of the bout. Adding insult to injury, “Yaqui” was taken for the majority of his $7,500 purse by the promoter who handled the show.

Moving forward nonetheless, three more knockout wins placed Lopez in position to challenge Victor Galindez in Rome, Italy for his WBA light heavyweight belt in September of 1977.

Lopez again lost a highly disputed decision in a title try, again in Europe.

“I was cheated out of the title,” he said immediately after the fight. AP correspondent Hilmi Toros reported from Rome that the Palazzetto dello Spot’s crowd sat in “stunned silence” following the verdict. “‘A very difficult fight,’ Galindez said, unaware of [Lopez’s] mourning next door. ‘Lopez is a good fighter, but I think I won this.’ Galindez was one of the few who thought he did. A crowd of about 8,000 disagreed with the decision that awarded the hard-fought 15-rounder to the light-heavyweight champion from Argentina,'” reported Toros.

Again “Yaqui” ran through three more opponents, then trounced contender Mike Rossman, rated #1 at the time, in six rounds.

Lopez was granted another stab at Galindez in Italy, but lost via decision once more in May 1978 by close scores.

Bouncing back with a decision win over old foe Jesse Burnett, who by this point had become a proven road warrior, two months later seemed to be exactly what Lopez needed to ready him for a brawl with NABF light heavyweight titlist Matthew Franklin in October of that year.

*******

The first epic slugfest between these two pieces of steel is less-frequently recognized among the best fights of the last few decades, despite being just as brutal and exciting as most of them.

Saad Muhammad later credited Lopez with teaching him the “art of true war” in their first bout. The Philly fighter, who had a tendency to act cocky and brash, came to truly respect Lopez following the tilt — so much so that he promised Yaqui a title shot should he ever become champion.

The fight itself featured a handful of ridiculously entertaining swings in momentum, and there were extended periods when Franklin and Lopez took turns thudding shot after shot at each other. The 8th round in particular is exquisite. Franklin, as he always did, weathered the storm, and referee Frank Capuccino stopped the fight with Lopez obviously staggering at the end of the 11th round.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmYQJ1LvzeE

Before their rematch a little less than two years later, both men stayed busy.

Franklin engaged in yet another tumble with Marvin Johnson, who was making the first defense of his WBC light heavyweight title. Blood and guts again spilled all over the place as they wobbled one another before a crimson-covered and puffy-faced Franklin stopped Johnson in an epic 8th round.

Not long after becoming a titlist, Franklin converted to Islam and became Matthew Saad Muhammad. Four months after obtaining the belt, Saad Muhammad defended his WBC crown against the former WBC champ Conteh, winning a decision. It took savvy from Adolph Ritacco, Saad Muhammad’s cutman, to see the latter through to the late rounds of the bout, though, as Conteh’s jab worked over Saad Muhammad’s face something horrific in the middle rounds.

Conteh again attempted to regain his belt in March, 1980, but was cut down in four rounds by Saad Muhammad. Conteh would later say that Saad Muhammad was both the hardest puncher he faced and one of the fastest fighters he knew.

Saad’s last defense of the title before granting Lopez his promised shot was against a fighter from Cameroon named Louis Pergaud, who he beat by TKO5 with a single, disgusting left hook.

Lopez fought seven times between their fights, losing only once to unbeaten Rahway State Prison inmate James Scott by decision. Lopez and promoter/manager Cruz would later say that while Lopez submitted to a drug screening for the bout, Scott refused but was never penalized. The loss also started rumors that Lopez had become “shot.”

He appeared to do just fine in earning two stoppages going into the Saad Muhammad rematch, though.

More importantly, Lopez started off convincingly well in the early goings of the second fight, which was held in McAfee, N.J. Building a comfortable lead on the cards, though not without absorbing leather in the meantime, Lopez worked a steady jab and busted Saad Muhammad’s face up.

The comeback kid didn’t disappoint, however, and a furious and exhilarating 8th round marked the start of all out chaos as Saad Muhammad came back, then Lopez did, and so on, until an exhausted Yaqui Lopez was floored three times and stopped by a final big straight right that dropped him to his knees, blood streaming from his nose, in round 14.

Matthew Saad Muhammad vs. Alvaro Lopez II was the runaway winner of Ring Magazine’s awards for Fight of the Year and Round of the Year (Round 8) for 1980.

Lopez would later say that the $50,000 he took home for walking through Hades with Saad Muhammad the second time was the highest purse he’d ever received.

After the bout, Lopez said of Saad Muhammad, “If I had gone for the knockout, I would have gone home early. He’s not a great fighter, just a great puncher.”

Saad Muhammad’s post-fight comment: “I was aware of every moment of the fight. The pace was very fast. And I was getting careless. Yaqui is a very experienced fighter, but I proved myself to be unbeaten.”

Matthew Saad Muhammad, 1954-2014.

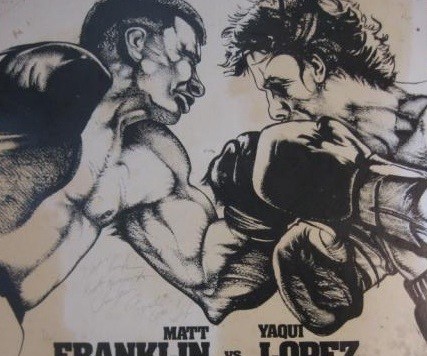

(image via Heavyweight Collectibles)