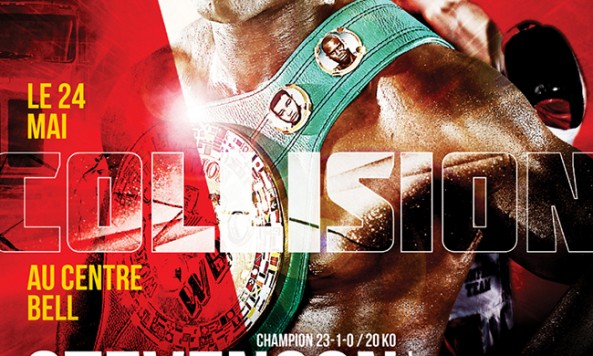

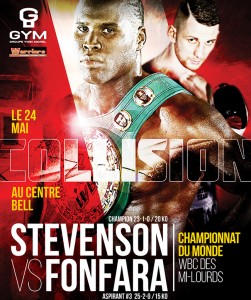

This Saturday, light heavyweight champion of the world Adonis Stevenson makes his debut on Showtime, a downpayment that will begin to determine how much uncanny punching power it takes to erase fans’ animosity for spoiling perhaps the best fight in boxing. That fight, a drool-worthy match-up with Sergey Kovalev, is the subject of litigation after Stevenson took a better offer from Showtime to face Andrzej Fonfara, lured by a Faustian bargain with top boxing manager/advisor/conquistador Al Haymon away from HBO. In that one fell swoop, Stevenson turned himself into one of the most hated figures in the sport.

This Saturday, light heavyweight champion of the world Adonis Stevenson makes his debut on Showtime, a downpayment that will begin to determine how much uncanny punching power it takes to erase fans’ animosity for spoiling perhaps the best fight in boxing. That fight, a drool-worthy match-up with Sergey Kovalev, is the subject of litigation after Stevenson took a better offer from Showtime to face Andrzej Fonfara, lured by a Faustian bargain with top boxing manager/advisor/conquistador Al Haymon away from HBO. In that one fell swoop, Stevenson turned himself into one of the most hated figures in the sport.

And it’s not as if he didn’t have a head start. Stevenson goes by the nickname “Superman.” That probably explains the choice by Showtime, while advertising Stevenson’s fight this weekend, to give the commercial a soundtrack that features the lyrics “let me be your hero” and “I can be your hero.” But it is an ill-advised musical accompaniment. Boxing fans are bitter beyond comprehension over Stevenson’s move away from Kovalev, a distinctly non-heroic maneuver, whatever kind of sound business sense can be attributed to it. The “hero” soundtrack is even less apropos when you take into account Stevenson’s dalliance with an underage prostitution/fight club/rape gang as a youth, some of which is more than mere “alleged” wrongdoing on Stevenson’s part. Whether you can forgive and/or forget what a 36-year-old man was up to as a young 20-something, no matter how egregious, is up to you; the amount of brave, selfless behavior it takes to erase any of that and jetpack all the way to “hero” status is far beyond anything Stevenson has managed.

When Stevenson-Fonfara was the penultimate chapter to Stevenson-Kovalev, it was tolerable. Now that it is the prelude to Stevenson-Bernard Hopkins, it is less palatable. Make no mistake, Stevenson-Hopkins — the fight Showtime, close partners with Hopkins’ Golden Boy Promotions, clearly targeted when it stole Stevenson away from HBO — is a quality fight. Stevenson is the clear champion of the division. Hopkins, by resume, is the clear #1 challenger. It’s just that Stevenson-Kovalev is so damn fun on paper as a meeting of two of the sport’s finest punchers, it rivals and perhaps surpasses Floyd Mayweather-Manny Pacquiao as the bout most desired by boxing’s long-suffering diehards.

That is the story that brings us to the precipice of Stevenson-Fonfara. Let us consider Stevenson-Fonfara on its merits.

The fact of the matter is that, if all you knew about Stevenson is what you saw when you watched him fight, you would love him. The power he possesses is, indeed, super. There might be no one with more exhilarating one-punch knockout authority. Among the contenders: Kovalev usually wears people down by combination before giving the bras d’honneur to their waking hours; Lucas Matthysse has been defanged slightly over his last two fights; only Gennady Golovkin contends and, as of now, he hasn’t faced anyone as good as Stevenson has beaten. And Stevenson is no mere slugger. Even at 36, he is quick and athletic, delivering his dynamite with springy leaps. His southpaw stance and steadily improved technique under Emmanuel Steward and then Sugar Hill — even in his last fight, against Tony Bellew, he was demonstrating new wrinkles — means that when he can’t immediately detonate, he’s capable of setting a time bomb.

Whereas Stevenson offered up a 2013 Fighter of the Year candidacy with wins over Darnell Boone (avenging his only loss), Chad Dawson, Tavoris Cloud and Bellew, Fonfara did himself one sizable favor in that frame. He scored his best win, a late stoppage of Gabriel Campillo in a fight he was losing. His next best win, in 2012, came over a badly faded Glen Johnson. A right hand injury left most of his 2013 limp, however. He is an authentic top 10 contender, and if Stevenson had already beaten Kovalev and/or Hopkins, we wouldn’t think too ill of this meeting.

Fonfara brings size, at 6’2″, not that Stevenson, at 5’11”, isn’t used to being the shorter man by now — Bellew was 6’3″. Fonfara is a bigger puncher than Bellew, though. He’s an actively good one (and, wags would note, he has a much better KO record after his 2009 performance enhancing drug bust than before). His main offensive weapon is the 1-2, although he mixes in left hooks and the occasional uppercut with either hand, mixing things up just enough to make the 1-2 effective. He has negligible interest in body punching, yet helped finish Campillo with a body attack. He is not fast — just faster than a fair number of his opponents. His defense is stiff, with a high guard, vulnerable to being penetrated underneath, down the middle or around by anyone who puts more a couple shots together. Back in 2008, he got smooshed by gatekeeper Derrick Findley in two rounds. But he has a fighter’s spirit where travails often translate into triumph, as exhibited against Campillo or in his last fight, when Samuel Miller rabbit punched him and Fonfara got angry and stopped him with a left hook seconds later.

All of this adds up to moderately difficult fight for Stevenson, at best. It might be a harder fight than Bellew, who is a better pure boxer than Fonfara and gave Stevenson few counterpunching openings early. The more naturally aggressive Fonfara might find himself giving Stevenson too many opportunities and retreating sooner than he intended. Fonfara can fight off the back foot a touch; it’s not his inclination. His best chance is landing a miracle shot early, and that’s not the kind of chance anyone would be wise to bet upon. All the time he’s trying, Stevenson will be landing pretty much at will. Stevenson by knockout around the midway point of the fight, if not sooner. There would be nothing funnier than to see Fonfara KOing Showtime’s prize in its war with HBO, but waiting for that laugh to come is as fruitless as doing the same while watching a two-hour Dane Cook special.

Will such a knockout make people begin to put Stevenson-Kovalev and the rest of it out of mind? It’s possible. But it will only be a beginning, at best.