Returning home at around midnight last night, I switched on the earlier BoxNation card and gamely attempted to stave off sleep. It didn’t work. No sooner had I watched Chris Eubank, Jr. destroy another journeyman when I promptly dozed off. I awoke some two hours later, in the midst of Mike Perez’s entrance for his heavyweight bout against Bryant Jennings, absorbed some unimaginative pontification regarding the fate of Magomed Abdusalamov, and proceeded to blink wearily through the opening rounds. Just as the fight appeared to be slipping into the realm of a lullaby, Jennings clawed himself back in — or rather Perez seemed to lose all interest — and the fight remained on a knife edge until the final round.

By this time, I had perked up somewhat, and the prospect of seeing some Kazakh thunder, not to mention the Max Kellerman-fueled hype train in full motion, had done more than a 3 a.m. cup of coffee ever could. You see, Gennady Gennadyevich Golovkin is a fighter who gets people excited. He demands your attention, and has developed a means of holding it even once the final bell has sounded and the night has devolved into little more than pantomime, a chorus of whoops and cheers as the middleweight kingpin repeats the name of HBO’s interviewer and lists the various fields of human endeavour for which he maintains respect.

For all his cherubic mannerisms, the man is a surgeon in the ring. From the moment he enters the operating theatre he is calculation personified, every move a testament to economy, patience, and an uniquely cerebral brand of brutality. His latest opponent, former beltholder Daniel Geale, had talked of the need to pose questions in the opening rounds, to give Golovkin angles and looks that would make him pause, potentially sowing seeds of doubt that would be watered and grow as the rounds wore on. Yet there were no questions on display, no room for rhetorical maneuver nor space in which debate be allowed to root. There was only emphatic statement, an unequivocal volley of facts delivered with both fists.

Golovkin has been compared to a freestyle swimmer in the past, but to me he’s more of a shark — an undisputed master of all he surveys. His opponents appear in uncharted waters from the initial seconds, required to work inhumanly hard just to stay at a comfortable distance. And there is no question of running, not against a man who cuts off the ring with the precision of a guillotine. Bizarrely, this lack of weakness, this absence of an Achilles heel through which to maintain suspense, can make his fights seem pedestrian, almost dull at times. It sounds counterintuitive, and I certainly feel a little sheepish when I contemplate it, but there were moments when I watched this weekend’s bout with an indifference brought on by the near total lack of hope Geale could lay claim to. Of course it’s boxing, and one punch can always change things, but this was as near a formality as is possible when both competitors are comfortably ranked inside the top 5 of their division.

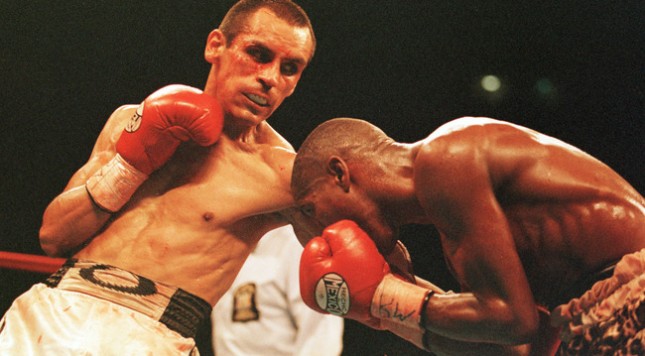

Golovkin, then, is non-fiction incarnate. He is a lithe, dexterous slice of reality, in much the same way as Ricardo Lopez once was. In fact, watching his latest performance brought back vivid memories of the undefeated Mexican great, the man they called El Finito, who was so dominant he notched up 26 world title defenses (tying Joe Louis’s record) before retiring unblemished. Lopez was “The Simpsons” to Juan Manuel Marquez’s “Futurama,” a man whose immaculate technique was matched only by his mental agility and skills in adjusting to whatever his opponents could bring.

Floyd Mayweather himself has talked of Lopez as his favourite fighter, the man he idolised while growing up, and it’s not hard to see why. Floyd is nothing if not a student of the game, and Finito was a fighter who did everything the way you’re supposed to. Not only did he maintain perfect form and position at all times, but he even brought a scientific exactitude to the improvisational aspects of the game, the feints and the finishes, those moments when it appears instinct takes over — the stuff you can’t teach. If you were to open a training manual on these subjects, a diagram of Ricardo Lopez would accompany the definitions, such was the flawless poise with which he pulled them off.

Yet there is a stain on his legacy, one that Golovkin is fortunate enough to have swerved by virtue of genetics. It is an injustice that rears its head on an almost weekly basis, and is so rampant in some boxing hotbeds that it is barely deemed worthy of comment. I am talking, of course, about the suffrage of the strawweight, the malaise of the minimumweight. The near total ostracisation of anyone below 118 pounds.

For all boxing’s oozing wounds, those untended, weeping fault-lines that sabotage any hope of true progress, perhaps the largest pock-mark is also that which elicits the greatest apathy, the flaw most likely to bring forth a shrug in the collective mind of the fans. We may fume at the ineptitude of the sanctioning bodies, or throw up our hands at the sight of lineal champions taking on opponents outside the top 50 in the division below (see Danny Garcia vs Rod Spalka, live on the glorious Showtime network on Aug. 9). Yet there’s an argument that the most brazen injustice the sport endures stems not from incompetent TV executives or short-sighted hangers on, but from us — the wholesome, long-suffering audience.

In the past month we have sighed at the news of a Mayweather/Marcos Maidana rematch, shrugged absently at the aforementioned Golovkin taking on Geale, and looked on with thinly-veiled contempt as confirmation of Manny Pacquiao vs Chris Algieri filtered through. In all these instances, there was little anger towards the A-sides, no real ill-feeling at the uninspiring contests into which they entered. Rather, the indifference was a reflection on the overall picture, or rather the absence of colour within it. Put simply, these three fights were just about the best available to each man at the time — a fact that gets no less ridiculous the more often repeated.

But pause for a moment and jump down 30 pounds. You’ll find a landscape as dramatic as the Andes itself. In fact, there’s a strong argument to be made that flyweight is currently the strongest neigbourhood in boxing, especially given the cold war divisions that run rampant through the higher weight classes. Akira Yaegashi is as accomplished a champion as almost any in the game, Juan Francisco Estrada continues to improve (and is still so young), while the likes of Giovani Segura and Brian Viloria always bring excitement, whether through Fight of the Year slugfests or frustratingly inconsistent glimpses of brilliance. And that’s all without mentioning Roman “Chocolatito” Gonzalez — the undefeated phenomenon who is criminally absent from much of the pound-for-pound reckoning, having conquered the two divisions below and now preparing to challenge Yaegashi in September for flyweight supremacy.

There have been many attempts to explain the disinterest shown to these pint-sized prodigies, but the frequent citing of a lack of English-speaking talent doesn’t quite wash. Of course, a great number of the best small fighters come from Latin America and East Asia, but since when have language barriers held back the likes of Julio Cesar Chavez and Roberto Duran? Or even GGG, who seems to be developing a kitschy dialect all of his own, and is curiously made all the more marketable for it. What’s more, all of the aforementioned flyweights have shown a willingness to get in and fight the best opposition, a fact which only adds to the mystery when we consider the wave of soft-matchmaking currently washing over so many would-be stars.

What we are sadly faced with is a situation in which the limited number of prime American TV dates are forced to accommodate the likes of the aforementioned Garcia vs Salka, as well as Keith Thurman vs Julio Diaz, and Matt Korobov vs Jose Uzcategui. The so-called “Glamour Divisions” are getting less glitzy by the day, while the likes of Gonzalez and Estrada are left out in the cold, forced to fight in far-flung locations like Macao, watched by an audience that neither knows nor cares what they are seeing. Golovkin might have a distinct lack of worthy challengers at present, but he will always possess the inordinate boost that nature provides. Even if he never lands the big one, GGG’s concussive power will likely be talked about amongst even casual fans for years to come. The 108 pound Ricardo Lopez, by contrast, can enjoy no such luxuries.