“The sweet science is joined onto the past like a man’s arm to his shoulder.” – A.J. Liebling

Since I began to write boxing with a degree of seriousness last year, I’ve had a notice set on my browser which dings ostentatiously every time a new piece by Springs Toledo is published on The Sweet Science. I can’t imagine I’m the only one. One solitary Google Alert may not seem significant, but there’s a reason he’s the only author I’ve chosen to single out in this way. Contemporarily, the man is quite simply unsurpassed when it comes to that interstitial space between stale round-ups of fight cards and titanic, leather-bound tributes to bygone eras, known rather plainly as the boxing essay.

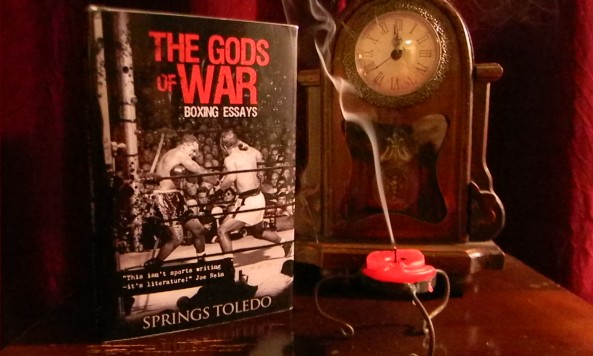

Not quite a column, and certainly not a news piece, essays on the sport offer perhaps the purest link to the writings of yesteryear, when boxing’s golden age felt as though it would last forever and newspapers devoted plentiful inches on the state of the game, as well as ringside accounts that granted the reporter a license to soar, rather than a digital deadline and a keyword quota. Here, in “The Gods of War: Boxing Essays: (Tora Book Publishing; TQBR was provided a review copy), Springs Toledo brings together a collection of some of his finest essays since mid-2009, before attempting what would for virtually anyone else seem a redundant and rather pointless task: naming the ten greatest fighters since the introduction of the Walker Law in 1920.

“They are not supposed to die. They are supposed to fade away; leaving heroes and myths intact as the rest of us march through this world as bravely as we can.”

If you had to boil down the strength of Toledo’s writing to one key skill, it would be his acute awareness of context, and the uncanny ability — present in many but not all great writers — to elevate the reader from the drudgery of the moment, to force them to zoom out and take stock of the grander narrative arch. Don’t believe me? Just take a look at his latest piece for The Sweet Science, which focussed on Paulie Malignaggi’s knockout loss to Shawn Porter and effortlessly invoked the wispy spirit of Willie Pep in the process. It is this talent that allows him to draw parallels without sounding trite between the likes of Peter Quillin and James Kirkland (footnotes in the present landscape, let alone the all-time picture), and the Sardiñases and Fraziers of the past. It’s also what grants him license to paint frequent pictures of the gladiators of ancient Rome — a somewhat tired analogy, clumsily drawn by lesser writers countless times in the past — without undermining the overall quality of the text.

While the overall hellenic thrust can sometimes feel a tad overblown, pieces like Black July and Alexis Arguello are worth the price of admission alone. As is the quadrilogy of “Liston Chronicles” devoted to the one and only Big Bear, covering both the infamy and greatness of Sonny with a tenderness that was so sorely lacking in his lifetime. Whether it be his astonishingly brutal formative years, the genuine terror he long inspired in the American public when he was little more than a snarling contender, or the oft-forgotten honour displayed by Floyd Paterson in granting him a shot at the title, the picture is fair and profoundly holistic. There’s also the unforgettable “ghost punch” of course, delivered by a nascent Cassius Clay, shattering Liston’s aura and going on to decorate the walls of student dormitories around the world. But this serves not to define him when properly contextualised and set beside his many triumphs, and it is to Toledo’s credit that he leans as much on the mysteries surrounding the year of his birth as he does that infamous first round.

“If you want to find boxing, you’ll find it where your grandfather usually found it – down and out in the gutter…”

It was, to all intents and purposes, a different sport back then. And thus the elegiacal tone of this collection of essays feels appropriate, whether they be in tribute to fallen heroes, journalistic inspirations, the aforementioned Liston, or, indeed, the wave of first generation Jewish-American fighters who all but dried up after the 1930s. That’s essentially what Toledo is offering up here, and it’s what adds weight to the book’s culmination: the 10 “Gods of War” from which the tome derives its title, the greatest warriors the ring has seen during the last 94 years.

Taking words like “definitive” and “objective” with a pinch of salt, the list is great in and of itself. The feats detailed are simply extraordinary, while the struggles endured merely to reach the stage from which to perform them are more impressive still, and, crucially, are each granted enough weight to propel one figure into the top ten despite never competing for a title at all. Toledo is able to paint pictures as vivid as the colour films of the 1980s, despite working from source material as grey and unreliable as the mid-Atlantic fog.

Upon reaching the segment devoted to a particular fighter I knew the author had never seen in action, my skeptical nerve began to tingle, and I approached the pages with a heightened caution. Yet, within the span of a few sentences, I was enraptured once again, not merely by the depth of knowledge and painstaking hours of research splayed over every page, but by the author’s uncanny gift for inserting the reader into the action, drawing on a profound understanding of the pugilistic condition to speculate with style on what it must have been like to witness those lawless scraps in the dingy watering holes of Pittsburgh, Chicago, and his beloved Boston. That should give you enough of a clue about who’s included on the list, but I won’t say too much more, suffice to say it’s tough to argue with any of the inclusions.

If I had my pedant’s cap on, I’d argue against inclusion of the scoring criteria, which is detailed yet never really addressed in the writing itself, and thus seems rather frivolous. Toledo’s words are too rich to be chained down by taxonomy, so the modest grid at the end of each fighter’s tribute — showing scores in categories such as “longevity,” “dominance” and “intangibles” — feels decidedly out of place, to the point that it quickly became an irrelevance. Put simply, mathematical criteria and boxing have never been easy bedfellows (as Toledo himself points out when decrying Bill Gray’s flawed attempt at cracking the same puzzle of the greatest seven hundred champions since 1882) and I found myself reading the list with the intention of learning what each fighter meant to author, rather than scrutinising the precise numerical formulas used to quantify greatness.

“The boxer himself is there too, but he’s standing up like he always has.”

It’s not cheap (at $25.00 or £19.99 for fans in the U.K.), but the book is a must for all those who value boxing’s heartfelt link to the past. If you’ve enjoyed the likes of A.J. Liebling and Norman Mailer you will find a fragile beauty at times overwhelming in Toledo’s work. He is a writer who’s at his best looking backwards, and at his best there’s no one better. A silver-tongued pathway flickers in reverse, past the Colosseum and the Empire of Rome, all the way back to the primordial. And in a strange way I find myself drawn once more to the image of Sonny Liston rallying against five policeman in a St. Louis alleyway, countless nightsticks broken over his head and discarded on the concrete, his hands remaining defiantly uncuffed.