Boxing overflows with victims. With no levee in place, fighters are martyred, managers are taken advantage of, men lose a competition, the winnings are plundered, and the cruel cycle spins forth unabated.

A fighter can either develop a monetary exoskeleton, as Floyd Mayweather Jr. has done, or tell the system to climb right on, as this isn’t your first rodeo, and buck it from here to kingdom come.

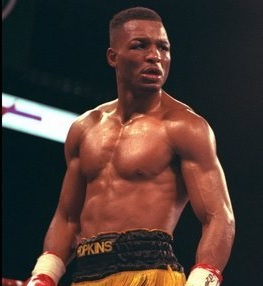

Bernard Hopkins, then more “Executioner” than “Alien,” chose the latter option. For most of his second life, his actions were deliberate and calculated, choosing to do things the hard way in every sense, even if only to reinforce an already potent will and further callus the skin. It might even have kept him crazily honest.

It was on July 20, 1997 that Hopkins foreshadowed his own greatness against Glen Johnson, who did the same, albeit in a more subtle way.

The Hopkins Legend began in Philadelphia, 1965. He was tempered and molded, early and often, by a mother who drank, a father who shot heroin, all in confines of shady Philly projects. Through petty theft that was replaced by strong-arm robbery, and finally landing in Graterford Prison with an 18 year sentence and almost 10 felonies to his name, Hopkins was run through his own life’s gauntlet.

When Hopkins caught on to boxing after leaving prison in 1987, he had converted to Islam and sworn off drugs, alcohol and things he considered junk food. Nonetheless, Hopkins lost his first professional fight at light heavyweight to a nondescript opponent named Clinton Mitchell. Rededicating himself, Hopkins returned to Philadelphia in 1990 and fought 23 times in the next three years. The famed venue The Blue Horizon hosted a number of his bouts, but he got to know Atlantic City quite well, too.

In May of 1993, Hopkins met up with Roy Jones Jr. for the vacant IBF middleweight belt in his first big stage fight. In dropping a decision to the future light heavyweight great, Hopkins actually kept up with Jones better than most felt he could, scoring points late in the fight as Jones looked to stay away. It was the wrong time, though, and the opponent was too good.

Scoring four wins in nine months, Hopkins was again given the opportunity to grab the IBF belt, but faltered against Segundo Mercado and being held to a draw in Ecuador. Hopkins pointed to issues getting to the high altitude country last minute, and being caught off-guard, having not been in the ring for over six months. And five months later, Hopkins avenged the stalemate with a stoppage over Mercado in seven bruising rounds.

Guiding Hopkins through the twisted maze of boxing, apart from longtime trainer English “Bouie” Fisher, was his flamboyant promoter Butch Lewis, also of Philadelphia. Lewis, who was later said to have swindled money from the Spinks brothers for years, was an establishment thorn in Hopkins’ side, and the fighter had difficulty hiding his general lack of trust in people, much less the man he suspected of taking money from him.

A few months after winning his first championship belt in the Mercado rematch, Hopkins announced that a law firm was investigating his finances and that he would promptly split from Lewis. Lewis allegedly had a deal with Hopkins — as he did with the Spinks brothers — to take half of his purses, which began adding up following the loss against Jones. Hopkins took the matter to court, attempting to sever ties with Lewis while getting back on track inside the ring.

Over the next year-plus, Hopkins leveled two solid contenders in Steve Frank and John David Jackson, and literally ended the career of then-promising prospect Joe Lipsey. He turned down big money offers from Lewis toward the end of his contract, which ended in the summer of 1997, when Hopkins was already 32-years-old. That was the point at which the long march began, with the world tapping its fingers, waiting for the reaper to escort Hopkins away.

Late promoter Dan Goossen headed a new promotional company called America Presents, which seemed to have the potential to compete with the Don Kings and Bob Arums of the boxing world. Hopkins came aboard, seemingly happy to break free from his old contract, but likely never truly happy with any form of structure he had to answer to. But craving unification, a Jones rematch and other larger opportunities, Hopkins invested, and a younger man, fighting under the same banner, named Glen Johnson was reserved a spot for their fight in Indio, Calif.

Born in Clarendon, Jamaica, Johnson would later say he watched his mother sell livestock on the side of road every day of the week to ensure Glen and his five siblings would be able to eat. But when Johnson was 14, his mother sent him to Miami so he could pursue something else. Johnson mostly worked construction when he realized school wasn’t a great fit for him. And at 20-years-old, he found boxing.In an interview with the Miami Sun-Sentinel, Johnson said of his career path, “I would probably be selling chickens and goats back in Jamaica, if I didn’t have this chance. There is no shame in selling livestock, it is what we do in Jamaica for food… It is a good living. But I think my future had something else in store for me. I think it was my destiny to box and to someday be a world champion.”

Johnson started out in boxing at the Miami PAL Club in Coconut Grove, Fla., learning all he could from coach Bobby Baker. At the PAL, he compiled a reported 55-5 amateur record, which included winning the Florida State Golden Gloves three times. Johnson and Baker split, ostensibly because Baker couldn’t take his student any farther, and he sent Johnson to future Olympic boxing trainer Pat Burns.Before turning pro, Johnson signed with Gerrits Leprechaun Boxing, Inc., started by Boca Raton millionaire Pat Gerrits, and tied to Gerrits Leprechaun Gym. Gerrits had renovated a Miami building following the 1989 riots, and turned the joint into a boxing gym. GLB Inc. paired up with the International Management Group, which was taking its first dip into boxing, having previously stuck generally to professional golf and recently picking up Tiger Woods as a client.

In just under four years, Johnson brought his record to 29-0 (20 KO), and was poised for a big opportunity when he got picked up by America Presents.

A slight roadblock arose in his fight against Sam Garr in February of 1997, as he suffered a cut near his right eye that required 11 stitches. After not having sparred much, he vanquished Dave Hamilton in June, but was cut under the left eye by a headbutt in round 2, not long before he dispatched Hamilton.Again Johnson was unable to train as much as he would have liked, but he flew to Big Bear, Calif. to train in altitude for the shot at Hopkins that he knew would be coming if he kept winning. Gerrits flew his old trainer Bobby Baker in to be in his corner, per Johnson’s request. In Big Bear, Johnson reportedly adjusted to the altitude well, and he sparred with then junior middleweight titlist Terry Norris.

Before the bout, Johnson said in an interview, “When you train around champions you begin to feel like a champion in that kind of atmosphere. I was around the real stars of boxing. I built up my legs and my body but also my mind.” And when asked about anxiety, Johnson said, “In a sport like this, fear always plays a part, but you have to be mentally strong enough for it not to play a big part. I have worked very hard to get to this point in my life. I always thought this day would come. It’s my destiny.”

In an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer before the fight regarding his recent promotional issues, and the fight, Hopkins stated, “I stood up for what was right, and now I’ve left all the tension, all the stress, home in Philadelphia. Hey, if you think Bernard was a killer, imagine what he’s going to be now with 99 percent of this mental thing buried.” He continued, “Nobody wants to fight me, that’s why I have a lot of respect for Johnson. A lot of people don’t know about him, but he’s the only ranked fighter [in the IBF] who was not afraid to fight me.”

Round 1 unfolded as any showdown between two natural counterpunchers would, as both men keenly analyzed the challenge at hand before exploiting what they could. There was a heaping tablespoon of aggression there, though, and Hopkins in particular landed heavy right hands that Johnson absorbed surprisingly well. And looking to make a statement, somewhat uncharacteristic riskiness from Hopkins carried over into round 2, where he answered back with venom every time Johnson spoke leather.

Already a backdrop in the 2nd, Hopkins’ body work was a nagging reminder of the difference between an undefeated record and an unbreakable will. If Hopkins wasn’t starting or finishing a combination with a rusty hook to the body, he was pushing them home in the clinch, which Johnson appeared to be thoroughly unprepared for. And another tactic had Johnson bedeviled: as the Jamaican transplant bent forward behind a high guard, Hopkins ripped uppercuts that regularly broke through.

Halfway through round 2, a salvo stunned Johnson, who could only cover up. He gathered his wits, but Hopkins’ body shots slowed him visibly toward the end of the round. In round 3, Hopkins’ offense became malicious — like he was punishing Johnson’s inexperienced attempts at gathering momentum with chopping right hands over the top and rib-softening body shots. It wasn’t like Johnson was impotent; the challenger moved quite well, just not as intelligently as Hopkins. Past that, Johnson’s own body work looked solid, but it was one-upped by Hopkins’ veritable disembowelment.

The 4th round saw matters become more physical and grinding, and Johnson sponged up a few terrific punches. His corner shouting from the sidelines, Johnson lashed out in the second minute, as his corner asked. But everything from Johnson save for his body work appeared tentative, as if he were afraid to dedicate too much and get countered. Worries that Hopkins would tire were put on hold, and his brisk pace continued on through the 5th, while Johnson’s left eye looked to be contemplating swelling up. Just when Johnson strung together a few nice jabs, a short right hand wobbled him, and Hopkins offered an in-ring workshop on mugging, with an IQ, before the bell.

Between rounds, trainer and commentator Gil Clancy praised Johnson’s conditioning, noting that he was taking hard punches surprisingly well, and weathering the hurt. In round 6, it was as if Hopkins placed a tourniquet on the bleeder, throwing fewer punches, but still inflicting pain. Important, though, was Hopkins’ ability to intimidate, as Johnson’s promising first half of the round turned sour, and he landed only one or two meaningful blows in the second half.

Perhaps unlucky, but more than likely due to jabs, Johnson’s right eye started closing up in round 7, just when Hopkins’ more careful approach would seem to pave the way for Johnson to create offense. Hopkins instead kicked back and got comfortable doing his aggressive, mobile counterpunching routine before eating a low blow that stopped the action. The respite had Hopkins fuming, apparently, and he closed the round strong, and mean as ever. Elbows, forearms and cuffing retribution gave way to a body assault that had Johnson wincing in the 8th round, and the fight was being extracted from him with every thump.

Sent out for round 9 conscious of his plight, Johnson jabbed while trying to find an opening, but was softened up for more pummeling at every turn. Referee Pat Russell, Johnson’s corner, and both commentators were all on the same page, calling for the fight to be halted if Johnson couldn’t muster an incredible comeback. The inability to scrounge up a miracle wasn’t for lack of effort. In round 10, Johnson minimized damage by playing defense, but like King Cnut, Johnson couldn’t stop the tide, and his right eye closed almost entirely at the bell.

The only person not threatening to pull the plug was the ringside doctor, who checked Johnson for all of one second or so between rounds. The judges had not given the challenger a single round of 10. Bruised, welted and sapped, Johnson dragged himself out for round 11 to meet the tide.

Hopkins descended upon Johnson in waves, appropriately. Johnson chucked a few haymakers to no avail, and mercy was shown just before the 11th round could hit the halfway mark. The collection of body work, plus a number of uppercuts had the referee seeing plenty, and stepping in to end it all.

Completing the defense number five of his belt, Hopkins soldiered on and fulfilled his destiny despite himself, defeating Felix Trinidad in a culmination of Don King’s middleweight tournament in 2001, then stopped Oscar de la Hoya to signal a more topsy turvy stage of his career. Greatness still followed, but the accolades died down, which is probably, secretly, how Hopkins not only likes it, but needs it. Controversy and adversity are fuel to Bernard Hopkins, and from De la Hoya to now, staring down Sergey Kovalev, is a decade of simmering brew.

Hopkins’ dispute with Butch Lewis would go on to become a recurring theme throughout his career. He clashed with other promoters (including Goossen and America Presents later on), with managers, with fellow fighters before and after fights, writers and fans. And he proved almost every single one of them wrong, at least once, and always the victim throughout.

Perhaps actually adding to the greatness of both Hopkins and his win, Johnson moved on to become the Road Warrior — not only by name, but by action. Whereas Johnson was known as “Gentleman Glen” back then, he elected a more painful and fruitless journey, fighting in 10 countries and dropping decisions he otherwise may have gotten, had he a more famous name or more slippery promoter.

One week after Hopkins scored his monster win over De la Hoya, Johnson marked his own with a one-punch KO of Roy Jones Jr.

While Hopkins’ career since then, on a chart, might look like the scaly spikes on a crocodile’s back, Johnson’s has been more parabolic in nature — like a junkie chasing the high, but never grasping it entirely.

Next month, Glen Johnson fights in country number 11, looking to become victim number infinity.

http://youtu.be/r4WBTBXxuG0