As boxing fans, we’re frequently thrown to the wolves, in a manner of speaking, in being forced to defend our sport, and fanaticism thereof. But the moments that speak to us, that wrench our emotions from whatever dark cave they may be huddled in, are easy to pick out.

We love action. We love skill. We love knockouts, drama, real humans elevating their own spirits — and ours — with leather, blood, tears and viscera.

Less clear is what exactly fuels a human being to willfully endure punishment for even the whisper of glory. It’s different in each case, truly. But peeling more layers can mean reaching microcosms that serve as lessons to those confused by the blood lust.

In The Heart of Midlothian, Sir Walter Scott wrote, “Revenge, the sweetest morsel to the mouth that was ever cooked in hell.”

While often considered a base motivation, revenge is a motivation nonetheless — and a fantastic one. Argentinian great Carlos Monzon fell victim to his id more than once, and on one of those nights, November 11, 1972, Bennie Briscoe shouldered the weight.

Born in San Javier, a part of Santa Fe, Argentina, Monzon was raised in poverty. One of 13 children, Monzon was made to drop out of school at the age of 10 and work small jobs to support his family, including delivering milk, and like many other fighters in gritty circumstances, selling newspapers and shining shoes.

Working away from home at a young age, Monzon learned to fight a style he would later liken to street fighting. On the streets is where a teenage Monzon would run into future trainer, friend and father figure Amilcar Brusa.

Under Brusa, who served as a sort of opiate for the raging Monzon, the Argentine would compile a reported amateur record of 73-6-8. In his final bout, he defeated a welterweight named Bienvenido Cejas by decision in five rounds, then turned pro at 20-years-old.

In a little over four years, Monzon fought exactly 50 times, earning a record of 40-3-6 (29 KO) and 1 No Contest. More important than the data, however, was the development of Monzon’s controlling, jab-heavy style. As Monzon learned the craft, so did his left hand, becoming a potent weapon that set much of his offensive work to task, but also one that could end fights, if necessary. But it was unknown how well Monzon’s linear style would be received by international audiences, and how he would fare against better opposition. His promoter, businessman Juan Carlos “Tito” Lectoure, encouraged his charge to reach out and grow as a fighter.

When Spring of 1967 crept around, Monzon had fought outside of Argentina four times: twice against Spaniard Felipe Cambeiro, going 1-1, and two draws with Brazilian middleweight Manoel Severino.

That was where Bennie Briscoe came in.

Briscoe, born in Augusta, Ga., wasn’t exactly summoned forth with a silver spoon in his mouth either; spoons were hard to come by altogether. Even literacy was a luxury, and the Briscoe family couldn’t scrape together enough letters to spell the word.

A move to Philadelphia guided Briscoe into the confines of the 23rd PAL gym, which would later be Joe Frazier’s headquarters for his entire career. There, Briscoe would amass a 70-3 amateur record, according to a 1963 issue of Ring Magazine. Along the way, “Bad” Bennie competing in a number of regional amateur tournaments before picking up the Diamond Belt — an amateur tournament sponsored by a handful of publications, perhaps most notably the Philadelphia Inquirer — in 1962.

Even early on in his career, Briscoe was a grinding, crunching type of fighter, carrying serious power in both hands, and a dangerous inside game that could net an opponent a thumb, low blow, kidney shot or elbow to the mush.

After his close loss to Stanley “Kitten” Hayward in December of 1965, AP writer Ralph Bernstein reported that Hayward was in such bad shape after winning, he spent a few days in the hospital.

He came a Philly staple, though, as outlined by later opponent Vinnie Curto. “I would’ve had to kill him to win [in Philadelphia]. They’d give him a draw from a stretcher.”

And it wasn’t just inside the ring, either. As a civilian, Briscoe was about as real as they come. J. Russell Peltz, legendary Philadelphia promoter, said of Briscoe in an interview with RingTV, “Bennie was one of the guys. He would hang out on the street corner at Broad and Girard with all the pimps and all the drug dealers and all the transvestites and then at the end of the day he’d go to the gym.”

Briscoe couldn’t keep the same pace as Monzon, in terms of activity, and racked up a record of 19-4 (14 KO) and 1 No Contest over four years. Only four of those opponents were batting below .500, though, and most had records much better than that.

A $7,500 purse coaxed Briscoe, who had only fought outside of Philadelphia once, to Argentina, in order to test the waters with Monzon. Briscoe was only a few months removed from a loss to former welterweight champion, “El Feo” Luis Rodriguez, and had halted tough contender George Benton late the previous year. He was tough and he was good, but not so good as to pose a woefully unnecessary risk.

According to reports from Estadio Luna Park venue, Briscoe’s performance was near-mythical, in some ways. A Buenos Aires publication said that Briscoe refused to sit between rounds and turned away water when offered, in addition to giving the already popular Monzon a terrific beating about his trunk. Walking through whatever Monzon’s right hand had to offer, Briscoe kept a stern pace and attempted to overwhelm Monzon when and where he could, but couldn’t pull away with the fight.

A report from Sports Illustrated’s Mark Kram years later characterized the contest and boring and tedious, with both men jockeying for position rather than throwing with bad intentions.

Whichever was the case, both men agreed beforehand that if neither was leading by more than three points at the end of 10 rounds, the fight would be declared a draw. So a draw it was, and the scores were not released to press.

Briscoe would later say that getting a draw against Monzon in Argentina was essentially the same as winning. And while Monzon was often outwardly lighthearted, his inability to truly hit pay dirt when necessary stung.

Madison Square Garden brass reported that Monzon was to have come to New York and face Luis Rodriguez, but more legal issues arose and Briscoe filled in instead in December of the same year. So it seemed that Briscoe’s stalemate against Monzon wasn’t fruitless, after all.

In the next three years and change, Monzon tabbed 27 more wins, and two draws. Lectoure brought in American fighters like Harold Richardson, Doug Huntley and Tommy Bethea to try his man’s mettle, but more slowly than even some of Monzon’s fans would like. Monzon was occasionally booed by Argentinian crowds — sometimes for employing a more cautious style than they preferred, sometimes for looking more vulnerable than they expected. Ring Magazine brought him into the middleweight rankings before nearly dropping him out entirely due to inability to make weight and struggling against a fringe guy or two.

In November, 1970, two very specific worlds — one north of the equator, the other below — were thrown into two different kinds of upheaval.

Giovanni “Nino” Benvenuti, middleweight champion and Italy’s hero, got Monzon to Rome for a crack at the title, but bit off far more than he could even fit into his mouth, much less chew.

From the outset, it became clear that Monzon, a 3-to-1 underdog, simply didn’t care what Benvenuti had to offer, as he raked the Italian in close with his gloves and elbows while Benvenuti looked for referee intervention. From afar, Benvenuti couldn’t handle Monzon’s speed and accuracy.

Monzon thanked Benvenuti for the $15,000 payday by staggering him in the 1st round and simply never letting up. Monzon was pushed back in rounds 5 and 6, but responded in round 6 by swatting at Benvenuti after the bell. Many of the 18,000 fans, who had broken the record for indoor sports gates in Italy, pelted Monzon with oranges after Benvenuti pushed the challenger in response.

Clearly being drained with every punch, Benvenuti was again rocked in round 7, then took a stand in the 9th, wobbling Monzon slightly. Monzon was no stranger to sea legs or seeing the canvas, though, and he pushed through to punish Benvenuti in round 11, before calling upon the sandman to mop up the mess a single Monzon right hand created in the 12th.

Fans rushed the ring in an attempt to nab referee Rudolf Drust, with police intervening just in time, perhaps sparing the new champion an extra few welts.

Carlos Monzon became a hero in Argentina by disposing of one in Italy.

The world his oyster, Monzon fought twice over the middleweight limit over the next three months before a non-title against Jamaican Roy Lee drew 21,000 in Santa Fe, putting to bed any notion that Monzon hadn’t become an overnight superstar.

Two months later, in May, 1970, Monzon offered Benvenuti a rematch in Monaco, despite that Benvenuti had only dropped a frustrating decision to Jose Chirino in the meantime, tasting canvas in the process.

Benvenuti hit the deck twice before his corner tossed their towel into the ring in round 3. An angry and dejected Nino Benvenuti refused to believe he had just suffered his third loss in a row, kicking the towel out of the ring and appearing to beg for the fight to continue.

The loss brought Benvenuti’s career to a close.

Over the next year or so, Monzon made four title defenses in four countries: Argentina, Italy, France and Denmark. A somewhat thin middleweight division meant the reach of matchmakers needed to be even longer than Monzon’s, as he defended against a musty version of Emile Griffith, Denny Moyer, Jean-Claude Bouttier and Tom Bogs, all by stoppage. It added to his legend, though, even if the defenses weren’t setting “all-time champion” lists ablaze.

“Bad” Benny was still in the back of Monzon’s mind. Briscoe hadn’t really gone anywhere, but he had his own difficulty staying consistent; it seemed he was either bruising foes, or getting out-maneuvered by them. In the five years since their first fight, Briscoe tabbed a record of 24-6, with only two of those losses coming against recognizable names in Rodriguez and Vicente Rondon.

A huge positive in there, though, was that Briscoe had signed with future legendary Philadelphia promoter Peltz, whose very first promotion at the venue The Blue Horizon had Briscoe vs. Tito Marshall as the main event. Together, win or lose, Briscoe and Peltz helped usher in a memorable age for Philadelphia boxing, and in particular, Philadelphia middleweights.

A return bout against Briscoe had initially been scheduled for July 22, but Briscoe asked for a postponement as he was recovering from hepatitis. Further issues, which were reported as “liver and stomach problems,” pushed the fight, which was rescheduled for August, back even more.

After defeating former European middleweight champion Bogs, Monzon said of Briscoe, “He is the toughest opponent I ever met,” and restated his intent to take on Briscoe again in October.

Benvenuti said of Monzon’s reign after the Monzon-Bogs fight, “There is nothing one can do about it. As long as Monzon’s energy lasts, the world title will be his.”

However, a busy schedule at Estadio Luna Park in Buenos Aires led to another postponement, pushing the fight into November. Not surprisingly, an early November date was scrapped for one a week later, as Monzon was facing assault charges for punching a photographer five years earlier — a recurring theme of trading one bout of vengeance for another.

A few weeks before the fight, Monzon did his part with a bit of pre-fight promotion, promising to take on light heavyweight champion Bob Foster if he beat Briscoe.

Briscoe, apparently understanding that he was at a disadvantage both stylistically and in terms of venue, said he knew he needed a knockout to win, telling an AP reporter in Buenos Aires, “…and I intend to do it!” He went on to add, “I hit as well or better than Monzon.” But, “If I don’t win strong and the fight is anywhere near even, with Argentine judges and the Argentine referee, Monzon is sure to be the winner.”

Monzon predicted a win by knockout in 10 rounds, while Briscoe’s trainer Quenzell McCall said, “The only possible way for us to win is by knockout. Here, the judges won’t give a victory on points to any foreign boxer.”

It was clearly very early that Monzon had developed as a fighter since their first meeting. Rather than stalling or idly outboxing Briscoe, Monzon castigated the challenger jabs for being foolish enough to bring a fight to him. Backward motion by Monzon only gave birth to countering combinations and pivots that left Briscoe reaching.

Briscoe wasn’t without claws, though, and every so often, he reminded Monzon that he was there by jabbing with him, banging at his body or raking with attempts upstairs.

In round 5, combinations from Monzon brought the crowd of about 17,000 to life; Monzon opened up the armory, landing hooks, overhand rights, uppercuts and every manner of poking jab in between. Briscoe didn’t give more than a step or two, but Monzon took the wheel and drove the fight like a bat out of hell — or out of San Javier, at any rate.

The Philadelphian inched closer to catching Monzon with something atomic, but Monzon’s upper body movement and slippery defense held steadfast. But not forever.

Per the UPI, “Briscoe, a veteran Philadelphia left-hooker, caught the taller Monzon with a right cross to the cheek in round nine, sending the champion into a corner, and badly dazed the champion. Monzon threw both arms around Briscoe in a desperate clinch. His eyes rolled and his knees buckled.”

Monzon draped over the top rope when crunched by the right hand, and he struggled to last through the round. It was only experience that pulled Monzon through.

After the 9th round, Briscoe refused to sit in his corner, attempting to stay warm following a huge round. In 12 years of competing as a professional fighter, this was his opportunity to slay the beast, and he would not succumb to fatigue.

Except for he would indeed give in. In round 10, Briscoe obviously wanted the belt notch, but Monzon had recuperated, using the ring to stay away and set the distance, and his spindly arms to safely wrap up Briscoe on the inside. Not only did it serve to neutralize the challenger, but it seemed to sap his will, too, and Monzon grabbed the momentum all for himself.

An AP report briefly described the rest, saying, “With Briscoe tiring, Monzon went on the offensive in the final five rounds, forcing Briscoe back into the ropes or into a corner. In contrast, in the early rounds, Briscoe had moved constantly forward, trying to get through to Monzon’s head and doggedly absorbing punch after punch to the face.”

Not totally content to pile up points, Monzon took initiative in round 13, accelerating his offense about as well as anyone in their 37th minute of fighting could do, and Briscoe took some of his first steps back in the contest. Ever the dog indeed, Briscoe fought back in the 14th, possibly winning just enough to call the round his, but not officially. The 15th round saw both men playing out their roles, only as exhausted, dehydrated versions of themselves, making for respectable action.

There was no question Monzon would triumph, just not without a serious scare. In fact, one judge scored no rounds for Briscoe outright.

There would be no argument from Briscoe this time, and he said after the bout, “Monzon’s a great champion. He clearly won.”

In an almost cartoonish display, the Argentinian president Alejandro Lanusse appeared on television to address Monzon, saying, “We were worried in that ninth round,” to which Monzon replied, “That was my worst round since I won the title, but I proved I can take it.”

A motherly quip from Lanusse followed. “You must follow the advice of your corner in a disciplined manner.” Monzon responded, “Well, Mr. President, they told me to attack his body, to grind him down like the others, but I just couldn’t. He was too short, too bent over and too well covered below. He was tough.”

Almost 5,000 of the 22,000 seats were vacant, per AP reports, but the turnout was still an impressive one, and Monzon walked away with $100,000. Briscoe more than doubled his take from the first fight with $20,000.

Monzon told reporters after the bout, in the third person, no less, “Monzon’s going to be champion for a good while longer. I’ve got a lot of mileage left.”

As it turned out, Monzon had more time remaining than mileage. In a sharp contrast to his early career, Monzon fought only nine more times over the following five years, defending his title eight times.

Violence, his in-ring mistress, joined him outside the ring for regular drinks. By only months after the Briscoe rematch. he had been seen publicly with a number of women, and they usually donned sunglasses to hide the bruises he gave them. Models, actresses, girlfriends, wives… All were targets. Even Monzon himself was a target, and he was shot in the leg by his wife.

Countless dramas, court cases and scandals passed, usually eclipsing Monzon’s in-ring triumphs. After having a difficult time in a second bout against Rodrigo Valdes, Monzon announced his retirement in 1977.

In 1988, he shoved his then-girlfriend, Alicia Muñiz, off a balcony to her death while vacationing. The following year, he was convicted of homicide and sentenced to prison.

While on temporary release from prison in 1995, the car Monzon was traveling in flipped, and he was killed, and his years-long mistress got the ultimate revenge.

As for Briscoe, his career ended rather poignantly when he told his corner mid-fight, against Jimmie Sykes, that he no longer wanted to do harm to his opponents. In December of 1982, it was all over.

He had defeated a number of contenders — popular and not — and kept it close with near royalty more than once.

Briscoe was and is regarded as one of the best fighters to never win a world title. Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, whom Briscoe defeated in 1975, said of “Bad” Bennie following his passing in 2010, “I respected Bennie and always will. When you fight Bennie Briscoe, you gotta bring your A-game. You can’t come in half-steppin’ and stuff like that. You gotta come right. He was a competitor and a credit to boxing. And a credit to Philadelphia. When you say Philadelphia you right away think of Bennie Briscoe. No nonsense, blue-collar worker. Bennie was the greatest fighter to never win a world title. You gotta take your hat off to him because he fought everybody and not just in Philadelphia. He went around the world.”

Boxing and revenge are old friends. The issue is that boxing is its own revenge. Nobody gets out unscathed. Not the “Bad,” and not the worse.

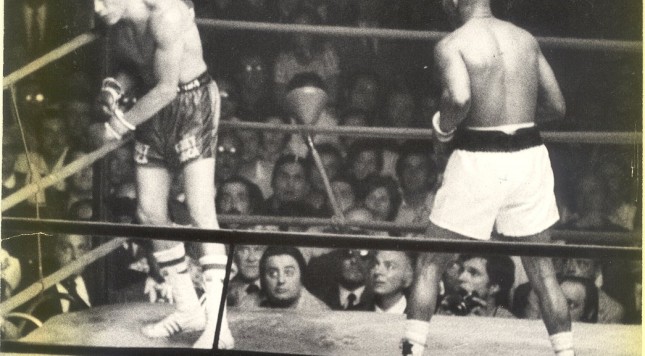

(Photo via)