Chewing through life a mile a minute and leaving messy footprints is just what many fighters do. Or did.

Few fighters make it to old age, marbles properly collected, and sometimes when they do, it makes no sense. They’re like the familial legends that saw a distant great uncle live to the ripe old age of 104 despite eating tons of salt, drinking and smoking every day for decades, and so forth.

Old grognards Jersey Joe Walcott and Carmen Basilio lived to see 80 and 85, respectively, and despite careers of hardship. Max Schmeling made it to 99.

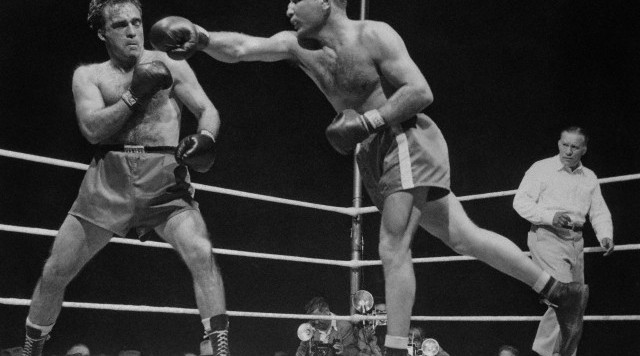

Jake LaMotta (pictured above, right; via) figures to challenge Schmeling, as he stands to turn 93 on July 10. And there might not be any other fighter alive that sweats aggression and bleeds cantankerousness as notoriously as “The Bronx Bull.”

Marcel Cerdan didn’t make it out alive, however. But the two met first, exchanging leather pleasantries and a belt on June 16, 1949.

LaMotta, an Italian from the Bronx, New York City, lived a stereotype from a young age — a stereotype that pointed him toward his red-stained and scarred destiny. At a young age, LaMotta was made to fight other kids in his neighborhood to entertain his father and other spectators. Eventually ending up in reform school, he began fighting in amateur tournaments as a heavyweight, and scrapped out a short but significant unpaid career. LaMotta’s most significant amateur achievement likely was being awarded the New York Journal-American’s diamond belt at light heavyweight in 1939.

He turned professional in 1941 after finding himself unable to serve in the military due to an earlier operation on his inner ear. Eight years later, LaMotta had garnered fame in facing “Sugar” Ray Robinson five times, defeating the flamboyant boxer-puncher once, but pushing him to a difficult end more times than that. But he’d also defeated other battlers Fritzie Zivic (who LaMotta would later say he would’ve liked to face at least “six more times”), Jose Basora, Holman Williams and Bob Satterfield.

The dingiest stain on LaMotta’s ledger was a November, 1947 technical knockout loss to manufactured and falsely-heralded Philadelphia light heavyweight Billy Fox. LaMotta would later admit to taking a dive in the fight that resulted in both men getting title shots; Fox would lose by knockout in less than a round to Gus Lesnevich in the following bout, and LaMotta was guided to a crack at middleweight king Marcel Cerdan, ignoring a tough loss to another Frenchman in Laurent Dauthuille.

While LaMotta was seasoned and tenderized by almost 90 professional fights, Cerdan held the experience edge with 114 bouts in almost 15 years. Despite the slight disparity, Cerdan was five years older, and had been collecting a paycheck in pugilism for going on 15 years.

The majority of Cerdan’s early career took place in Morocco and Algeria, earning him the moniker “The Casablanca Clouter.” He transitioned to fighting in France, Italy and Belgium, but scratching beneath the surface revealed that most of Cerdan’s bigger fights were of the regional variety, against opponents unheralded on the world scene. Despite winning the Second Inter-Allied championship while serving in Italy during World War Two, it wasn’t until a decade into his career that he tabbed wins over respectable names like Holman Williams and Georgie Abrams, then another nearly two years before ending a fading Tony Zale’s career in 1948, winning the middleweight title in the process.

Perhaps Cerdan’s most resounding accomplishment, however, was arriving as a legitimate celebrity in France while reigning as the French middleweight champion, then the European middleweight champion. A years-long love affair with famed French singer Edith Piaf made most news regarding the couple newspaper-worthy in France, and quite often in the U.S. And it was about to get better, as he’d just been offered a role in a Mae West picture before the LaMotta showdown.

The Cerdan-LaMotta bout was held at Briggs Stadium in Detroit, and was the first fight under the banner of the International Boxing Club — a promotional company started with the help of then-heavyweight champion Joe Louis, and to essentially counteract the influence of Mike Jacobs’ Twentieth Century Sporting Club, which previously held sway in Philadelphia, Chicago and New York City, among other cities. New promoter Nick Londes handled matters in Detroit. (The IBC didn’t last very long, however, and folded under its own corruption.)

LaMotta told the United Press that he would go directly into training for “my best chance since I turned pro in 1940.”

Cerdan rightly expected a rumble. His American representative Sammy Richman told the Associated Press, “LaMotta never thought he’d ever get a shot at the title. Now that he’s getting his chance at last he’s going to be mighty rough.”

Nonetheless, Cerdan opened up at a 12-to-5 favorite, though odds went down slightly to 2-to-1 by fight time, even though press noted that in 15 Detroit bouts, LaMotta had only lost once, and to Ray Robinson. The fight was priced right, though: $2 for spotlights to $16 for ringside.

AP reporter Jack Hand said pre-fight, “From the corner it looks like Cerdan, largely on the basis of the old cuts around LaMotta’s eyes that keep reopening in every fight. Marcel doesn’t hit hard enough to dump Jake on his panties but his slashing hooks are just the things to slice tender brows.”

The fight wound up being rained out and postponed a day. Prior to the postponement, LaMotta told AP reporters in an interview, “I’ve waited all my life for this. When they passed me up so many times, I sort of gave up hope. But now, I’m getting my big chance. Win or lose, I’ll ask no more. I fought for the title. You will see me fight like I never fought before.”

The man from the Bronx made good on his claim, rushing at Cerdan from the start and dissolving the space between them. But toward the end of round 1, Cerdan injured his left shoulder missing a punch, and it was exacerbated by a push from LaMotta that dumped Cerdan to the canvas.

A fateful injury had Cerdan initially believing he could beat LaMotta one-handed, but a jab from the Frenchman controlled round 2, to the surprise of LaMotta, who became more mobile, and afterward said, “I thought I had him in the first round, but he came out strong in the second round jabbing.” But with Cerdan’s injury, it couldn’t last, though he unlocked his right hand in rounds 3 and 4. Said LaMotta, “Cerdan stung me with his rights in the first couple rounds, then I started riding them and I didn’t worry about his rights anymore.”

LaMotta’s blunt account aside, two other things happened: “The Bronx Bull” was becoming worried about his energy reserve, and Cerdan further injured his shoulder in the 4th round.

Referee Johnny Webber said he heard “something snap” when Cerdan tossed what was essentially his final left hand of note in round 4. From that point on, he had only his right hand, which simply wasn’t enough.

Thereafter, Cerdan was slow-cooked under the nonstop fission of LaMotta’s output, which climbed as rounds went by. According to an unofficial ringside punch counter, LaMotta had settled down after the early jitters to throw 75 punches in round 8. The 9th saw his output — and by proxy his fury — grow to 104 punches.

Cerdan, draped into his corner like a freshly beaten throw rug, lay welted and swollen. Cerdan’s American managers Joe Longman and Lew Burston called the ringside physician to the corner between rounds, and decided to end the carnage as the bell rang to start round 10. Referee Webber concurred, and made it official.

Charles Einstein, ringside for the International News Service, reported, “It took nine years of blind and blundering hope, and a night of thunder and rain and tears, a thousand punches and a one-armed opponent–but Jake LaMotta today is the middleweight champion of the world. He stood in the middle of the ring at Briggs Stadium, the night clouds black above and the lights and the rain falling, and he cried. He looked over to a corner, 10 feet away, where the fallen champion, Marcel Cerdan, lay back on his stool, his left arm like the arm of a dead man.”

As the IBC had banned radio broadcasts at their inaugural event, there was no microphone for LaMotta to speak into.

A teary-eyed Cerdan told INS reporters in his room under the stands, “I did what I could. What do you do with one hand?”

An AP report via the Morning Star said, “It was a glorious victory for rugged Jake, the bull from the Bronx who entered the ring an 8 to 5 underdog because of several recent poor fights. This was the ‘new’ LaMotta. Throwing punches from bell to bell with none of those customary rest periods, Jake fought like a champions all of the way before a disappointingly small crowd.”

Walter “Red” Smith reported on LaMotta’s win for the AP, “It was not exactly a case of knocking a king off his throne. It was more like picking up the remains after a champion had fallen down an elevator shaft. …LaMotta, at his present day best, fought a man who had one hand tied down. Jake punished his almost defenseless adversary brutally yet he could not knock him out, could know score a legitimate knockdown, could not make him quit. It was Cerdan’s proprietors who quit after the ninth round, over Marcel’s impassioned Gallic protests. ‘Jake is going to be the greatest middleweight champion that ever lived,’ said Joe LaMotta, Jake’s brother and corresponding secretary. It remains to be established whether Joey is more to be admired for his prophetic gifts or his fraternal sentiments.”

Significant swelling on LaMotta’s left hand suggested he wasn’t the only injured man in the ring, though. LaMotta would indeed admit that he began moving more in round 2 because he was losing steam, but chiefly because he knew he had likely fractured his hand throwing a hook early in the fight.

All told, LaMotta took home an unknown share of $14,000 for the title win, while Cerdan pulled in roughly $50,000. The fight itself, financially speaking, was a flop with a gate of $150,000, and the profit only a few thousand dollars after Cerdan took his 40 percent, LaMotta took his 15, Uncle Sam his 25, and less expenses.

Afterward LaMotta told reporters, “Getting a chance at a title gave me incentive to work. I’ll fight anybody they say. From now on, while I’m still fighting I’ll always be in the best of shape. I found out that makes fights easier. When I get too lazy to work, I’ll quit.” When LaMotta was asked about his diamond-studded NBA belt — valued at $5,000 — he responded, “They wanted to take it to get my name put on it, but I said no. Nobody’s going to get this away from me.”

Meanwhile Cerdan flew to New York, both to get x-rays of his shoulder and to pick up $25,000 of his prize for defeating Tony Zale for the title the previous September. New York State Athletic Commission doctor Vincent Nardiello suggested that Cerdan had torn a muscle in his shoulder and would be out for at least a month, but might be able to fight again in September.

In a coincidental twist, a September rematch a few months later was derailed when LaMotta injured his shoulder a few days prior to when the fight was to have taken place. The bout was then rescheduled for December.

Cerdan would tragically perish in a plane crash on his way to the U.S. for training (and to visit Piaf in New York) one month later in October, however.

Through the years, LaMotta owned a night club, served time in jail and alternated between living through horror and creating his own. He’s still around, though. Like only a man hardened by battle could be.