Gauging the importance of a given fight in boxing is no easy task. It’s nigh impossible to put in stone exactly what it is that makes a bout important. There’s much to choose from, between attendance records and television views; world titles and simply how great the action is.

Are fights that usher in new eras of boxing less important?

Underrated on the grand scale of importance, then — if there is such a thing — might be a fight that both ushers in a new era and closes the door on an old one.

Aug. 18, 1936 was the day that Joe Louis, “The Brown Bomber,” unleashed his artillery upon “The Squire of Chestnut Hill,” Jack Sharkey.

*******

Two months prior, Max Schmeling, rabble rouser and certain terrible person, planted dynamite on the train tracks of Louis’ career with a stoppage win in 12 rounds. Schmeling’s comment that he “saw something” after Louis’ win over Paulino Uzcudun, whether myth or true, has come to mean that he saw Louis pulling his jab back lazily, which begged for a counter right hand. The plan paid off, and the new heavyweight champion walked away a celebrity.Louis walked away to slap on some brick and mortar patch work, rebuilding momentum.By contrast, Sharkey was fresh off of a fishing trip taken after a difficult fight against Phil Brubaker in Boston. “The Boston Gob,” as Sharkey was also known, was out to reclaim the heavyweight title.

Around the same time, Max Baer emerged nine months after his knockout loss to Louis reborn, bulldozing 10 Southern and Midwestern opponents, leading to speculation that a Louis vs. Baer return bout was next. It was a different heavyweight ex-champion that fit the mold, though.

W.A. Hamilton, always eager to lend a few cents, said, “When Sharkey started his comeback it was for the sole purpose of obtaining a meeting with Louis. [Sharkey’s manager] has long contended that Negroes were duck soup for him and a review of his past performances would appear to bear out his contention. When interviewed last night, Sharkey declared that the match with Louis justified one of the big ambitions in his life. ‘I don’t wish to make it appear that I am bragging. I have done enough of that in my time. You learn plenty as you grow older and I have learned my lesson, but I never was more confident of going to town in any fight than I am with Louis,’ Sharkey said.”

In July, Jack Sharkey’s manager Johnny Buckley met with renowned promoter Mike Jacobs in New York to demand a $50,000 guarantee for Sharkey against Louis. Buckey also managed Worcester, Mass.-based Canadian Lou Brouillard and helped guide him to a portion of the middleweight title. He worked some sort of magic in negotiating 25 percent of gross receipts for his man, with the New York Milk Fund getting a chunk of the Yankee Stadium gate. Julian Black, Louis’ co-manager, signed off on the deal.It was reckless, in a way, to assume that a 33-year-old Sharkey might actually be a viable contender or two-time champion, but he had the name, the demeanor and the experience. The few clams Sharkey had saved up had clapped shut in the preceding years, which perhaps called into question the sincerity of his intention to see a championship run through to the end, but it made him a hungry man, nonetheless.

In an interview about one month prior to the bout, former heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey claimed that Louis was no longer a first-rate fighter, saying, “I told them Louis was pretty tough about the jaw but that he couldn’t take punches to the head. And if he can’t take them there he will never be a great fighter. He may beat a lot of second-raters, but he won’t beat any smart fighters. That’s what I thought, and that’s what I said.”

Sports editor Houston A. Lawing was of a similar mind, relaying, “Announcement that Jack Sharkey would fight Joe Louis in a 10-round battle comes as the biggest laugh of the season. If Louis fails to plaster Sharkey in the early rounds of their fight then Jack Dempsey’s statement that Louis has a glass jaw will be a certain fact.”

But when Louis vs. Sharkey was announced, Louisiana sports columnist W.I. Spencer, who would later go on to judge a few fights, remarked, “Sharkey has been called by many the equal or superior of all modern heavyweights (which may or may not be a compliment) but has enjoyed the most checkered career of any fighter, with more ups and downs in it than Primo Carnera’s. In some trials Sharkey looked the master, in others he was the punk. He has been training for a year now, has whipped three ordinary pugs and then cut short the fast-rising career of Phil Brubaker, the west coast youth whom many thought would be the challenger by this time. Sharkey has repeatedly sneered that he can whip the socks off of Joe Louis, and when this Sharkey sneers a real honest-to-goodness sneer, I’m told the victims are wont to tear into their dear old mothers and brothers in venting their wrath. In other words, Sharkey can really provoke ’em.”

If throwing stones at a wasps’ nest, agitating a monster with a one-man hive mind to destroy was Sharkey’s aim, he succeeded.

Both men began training in familiar surroundings — Louis in Detroit, Sharkey in Boston — before heading out to New York for the final haul.

Sharkey claimed to have seen something in the way Louis fought, too, only in this case it was Louis’ scrap with Max Baer. In a letter sent to the press a few weeks before the fight, Sharkey penned, “They ask me if I’m scared of Louis. The night Baer took that runout powder settled the fight for me. I shall beat Louis. I have always had the Indian sign on negro boxers. Remember what I did to George Godfrey and Harry Wills?”

The “Gob” opened up fighting as if he expected to be able to handle Louis’ punching power, lazily grabbing at the younger man’s elbows with his back to the ropes, while Louis simply used speed and volume to get work done, his power not yet a significant factor.

Sharkey’s movement wasn’t without nuance or skill, but he was not the same man who, 10 years earlier, defeated Harry Wills, George Godfrey and Mike McTigue in the span of six months. (Sharkey would later say that he paved the way for Dempsey to win the heavyweight title by essentially defeating Wills and Godfrey for him.) Constant jabs from Louis had Sharkey resetting his stance and mode of attack, with his attempts to maul his way in either stifled by Louis or stopped by referee Arthur Donovan.

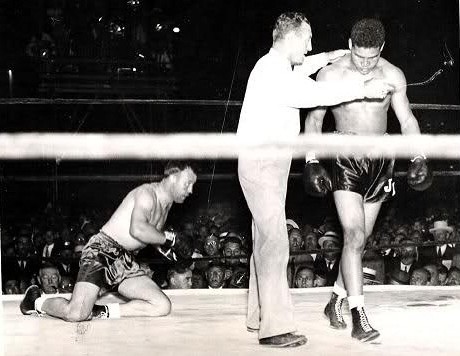

Round 2 saw Sharkey looking to mesmerize Louis, a 7-to-5 favorite, with his upper body movement before lashing out with jolts upstairs. Louis, unimpressed, backed Sharkey to the ropes even more often, timing his movement with sharp punching. Sharkey appeared to believe in his power — or potentially in Louis’ lack of chin — as he waded in, committing more of his weight to punches. The combination of Sharkey’s hubris and Louis’ jab led to Sharkey absorbing a right hand that deposited him straight to the canvas. Up somewhat slowly, Sharkey digested a few more shots before again hitting the deck in a similar way. He bought time to make it to the bell, shifting this way and that to avoid getting stopped.

A chopping kind of right hand to the temple early in the 3rd round confirmed that Sharkey’s legs had disappeared, putting him down once more. Up and once again foggy, a left hook from Louis stood Sharkey up, and a left hook to the body, right uppercut and left hook up top leveled Sharkey entirely.

An AP report of the bout said, “The glowering Gob was sullen. Blood dripped from a cut over his left eye, and trickled out of the corners of his mouth. As he walked into his dressing room with his hands on his head he did not know that he had been knocked out in the third round.”

Over in Louis’ dressing room, quiet celebration and media rounds were interrupted by a girl claiming to be Louis’ sister, wanting to make sure he was okay. She was turned away by John Roxborough, Louis’ other manager, with the promise that Joe would shortly present himself to prove he hadn’t been hurt.

Another Sharkey, this time “Sailor Tom,” a former bare knuckle brawler and heavyweight title challenger, had his own opinion of the future heavyweight champion: “Louis looked great when he was winning, but when put to a real test was revealed in his true light. Louis may yet come back to make good but I have my doubts about it. The Negro youngster didn’t have enough really tough fights to prepare him for Schmeling, who while not a great fighter, is tough and game. Joe wouldn’t have lasted half as long as some of the old timers I could mention, like Fitzsimmons and McCoy for instance, and that goes for Schmeling and the rest of the present crop.”

Joe Louis would advance to take on the world, before becoming one of the greatest heavyweight champions ever to rule the limitless class. In one of the most widely-covered and far-reaching boxing matches ever, Louis would retain the heavyweight title with a 1st round KO of Max Schmeling, almost two years to the day after the German stopped him and derailed his career. Louis would go on to face many a pug, amassing a record 25 defenses of the heavyweight title.

Jack Sharkey would advance to take on the world outside of fighting for money, retiring to New Hampshire to fish, hunt and occasionally referee a boxing or wrestling match. The most famous bout Sharkey had any involvement in was the epic first donnybrook between Archie Moore and Yvon Durelle in Montreal that saw both men hit the deck four times. Sharkey finished his career as the only man to have fought two separate sets of heavyweight champions that never faced one another: Dempsey and Schmeling, and Dempsey and Louis. But Sharkey had success in walking away from the game — maybe the most important success of his career.

http://youtu.be/tUTL-cgg3oI