There’s boxing the sport, and there’s boxing the business. Often the two are the same, but usually the latter trumps the former, and even when it makes no sense in hindsight.

One thing boxing tend not to be, though, is patient. Instant gratification triumphs over the greater good with regularity, and especially at the negotiating table. There’s always collateral damage too, and fighters, resilient by nature, absorb the majority.

As boxing increasingly relies on networks and technology, television dates have become the currency. And because high-paying dates are scarce, there exists a sort of triaging of possible fights vs. likely financial return, and losses mean more in the short term. It also means there are rematches that never come — business, after all, is business. When there are bigger fish to fry, the win is more important than almost anything else.

On January 25, 2003, an HBO telecast produced a wacky engagement for a few different reasons. On the surface, a new star emerged in Nicaraguan lunatic Ricardo Mayorga, injecting further interest into a division that had already been good for about a decade. But flying just under the radar was Joel Casamayor’s struggle against comparatively unknown Nate Campbell, which produced its own intriguing narrative that evening.

Casamayor, born in Guantanamo in 1971, became a product of the Cuban boxing machine early in life. Heavyweight sensation Teofilo Stevenson was nearing the height of his popularity and amateur brilliance when Casamayor was a young, impressionable boy, and before long, Casamayor was also making waves.

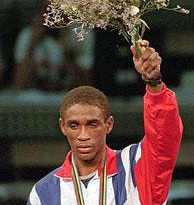

A neighborhood gym in Guantanamo introduced Casamayor to boxing, and he began winning competitions against other gyms nearby. Eventually Casamayor’s amateur wins carried wider and wider implications, and he did well through the regional, provincial and national levels. In a 2008 interview with Bill Dwyre of the LA Times, Casamayor said, “I had a trophy case, with 200 trophies on the wall.” Included in his amateur wins was a gold medal in the 1992 Olympics, alongside numerous wins at the international level.

According to Casamayor, Cuba gave him a bicycle for his gold medal in Barcelona. But he had heard stories of the endorsements and celebrity of Olympians in the United States, and the cars and houses given to Russian athletes, and he wound up having to sell the bike to get a pig for his family anyway. Beyond material wealth, Casamayor claims he was being commanded to make the bantamweight limit, which he could no longer make.

While training for the 1996 Olympics amid hefty expectations in Guadalajara, Mexico, Casamayor and his teammate, then-light heavyweight Ramon Garbey, told a security guard they were going to get bottles of water, and split from training camp. They made their way to the U.S. border just south of California, declared their intentions to defect from Cuba, and were accepted after some legal maneuvering from Top Rank leader Bob Arum. Garbey was Arum’s target, and Casamayor more or less came along for the ride, but both wound up commodities.

A second defection was in order for both men, as contracts signed with Top Rank were disputed after promoters Luis DeCubas (and DeCubas’ own Team Freedom, which sought to reunite and represent Cuban fighters in one camp) and Main Events got involved. More court shenanigans ensued, and after a chunk of money changed hands, DeCubas retained a good portion of control.

Turning pro in late 1996, Casamayor fought 13 times in about two years, and due to DeCubas’ managerial relationship with the Goossen family and distractions in Miami with DeCubas, Casamayor relocated and began training with Joe Goossen in 1998. Casamayor went on to win the interim version of the WBA junior lightweight belt before gaining the trinket outright in 2000 against Jong-Kwon Baek.

Five defenses of the belt led Casamayor straight to a unification with fellow belt-holder, Brazilian hero Acelino Freitas in 2002. The clash ended controversially when the highly touted knockout artist Freitas became the boxer and took a unanimous decision, after scoring a flimsy knockdown early in the fight, while Casamayor pursued him for much of the rest of the bout, surprising many.

Casamayor fought twice more in 2002, stopping both Juan Arias and Yoni Vargas. Joe Goossen would call Casamayor’s win over Vargas “the best performance I have seen from Joel since we started working together,” after the fight. It brought Casamayor’s ledger to 28-1 (18 KO).

Staying in Miami after the Arias win, Casamayor was to celebrate with family before he got the call that Vassily Jirov had pulled out of his fight against James Toney on the undercard of what was supposed to have been Vernon Forrest’s easy defense of the welterweight title against unheralded Nicaraguan brawler Ricardo Mayorga on HBO. Casamayor took the date rather than pass it up for extra vacation time, signing to take on undefeated hopeful Nate Campbell.

Campbell, a native of Jacksonville, Fla., entered into the government system at a young age. Whereas Casamayor was essentially bred to eat, sleep and bleed boxing, Campbell was simply taught to eat, sleep and bleed, though the eating part was tricky at times. When Campbell’s mother went to prison, her boyfriend that he was left with locked him in a closet for a few days before authorities intervened and placed a 4-year-old Campbell in foster care. A few years later, his father came into the picture before passing away when Campbell was only 10.

Back into foster care, Campbell’s tumultuous life began to take its toll before he moved in with his mother, who had recently gotten out of prison for the second time. At age 14, Campbell got his first job, but more came and went, and he dropped out of high school following his sophomore year. Campbell had a handful of arrests at ages 17 and 18, and then became a father, settling on full-time work at a local Winn-Dixie grocery store to pay bills for his family.

While on breaks, Campbell would apparently shadowbox, and his co-workers encouraged him to pick the sport up, which Campbell did. Despite excelling in multiple sports in high school, Campbell had simply never tried boxing beyond a few lessons.

As an amateur at 24-years-old, Campbell was apparently much better than would be expected from a later bloomer, demonstrating respectable punching power and respectable skills while fighting out of the “Boxing at the Galaxxy” gym in his hometown of Jacksonville. It was at this gym that Campbell would earn the nickname “The Little Warrior,” which later changed to “The Galaxxy Warrior.”

Gym owner Frank Jimenez said of Campbell’s initial experience, “He went in with the idea like, ‘I’m going to come in and show I can beat these guys.’ He probably hadn’t boxed in a long time. He kept shooting his mouth off, and I thought, ‘I’ll teach you something.’ The guys I put him in the ring with were seasoned fighters and had good pro records.” Campbell predictably took his lumps, but Jimenez continued, “He stuck with it. He took the punishment and he paid his dues. I’ve been coaching boxing for 25 or 30 years. He’s the first fighter I ever discovered and mentioned, ‘You’re going to be world champ someday.'”

Campbell managed to fight in a few tournaments, including one in which he lost to former U.S. amateur lightweight champion Jacob Hudson, whose reputation had grown after reportedly dinging up Floyd Mayweather, Jr. in a sparring session prior to the 1996 Olympic Trials. Campbell also fought his way into the 1999 US Nationals, but lost in the first round via controversial decision. All in all, Campbell finished with a reported amateur record of 30-6, earning the Florida State amateur championship at 132 lbs. from 1997-1999.

In 2000, Campbell made his professional debut, then fought 16 times in the next two years, going the distance only once. 2002 was Campbell’s breakout year, though, as he made serious strides with manager Jimmy Waldrop. Apart from fighting seven times, Campbell fought on the undercards of progressively popular boxing cards, peaking with a stoppage of Daniel Alicea with a single right hand on the undercard of Oscar de la Hoya’s halting of Fernando Vargas in September.

Prior to his first scheduled 12 round fight in March of the same year, Waldrop said of Campbell, “He has come forward by leaps and bounds. This kid has the rare combination of being a boxer and being able to punch. If he gets a shot at a world title, there’s a chance he could win it.”

A knockout win over unknown Renor Claure on the undercard of Arturo Gatti vs. Micky Ward II in November of 2002 brought Campbell to Casamayor’s doorstep, and in the opinion of many, prematurely. Despite resting in the competent hands of trainer James “Buddy” McGirt and training with fellow contender Daniel Attah, Campbell just didn’t have the same type of weathering and in-ring education as Casamayor, and with a record of 23-0 (21 KO), he was rightly pegged an underdog.

The general purpose of the HBO card at Pechanga Resort and Casino in Temecula, Calif., was to showcase Forrest, who had notched two wins over Shane Mosley the previous year and gotten a heap of good press for his charity work — two things that could potentially help make Forrest a crossover star. Forrest had just signed a multi-fight deal with HBO, and indeed, Forrest was supposed to have been the star of the show. Mayorga wasn’t interested in that storyline, however, and when part of the promotion at the weigh-in involved placing Forrest’s face on the lids of pizza boxes, Mayorga seized a slice for himself and chowed down while on the scale. It was the pugilistic equivalent of taking Forrest’s lunch money, which Mayorga would again do inside the ring on fight night, in three rounds.

Over the previous few years, Pechanga had emerged as a solid venue for fight cards, but had only showcased a few recognizable fighters like Antwun Echols, Ricardo “Chapo” Vargas and Derrick Harmon. In August of 2002, the venue welcomed James Toney, who was knee-deep in a cruiserweight comeback, in a show televised by Fox Sports Net that boosted the venue’s image some.

A Toney vs. Jirov undercard may have stolen the main event’s thunder, but while Casamayor vs. Campbell was a good replacement, it was bound to fly more under the radar than the cruiserweight contest. The replacement was mostly praised in hindsight, and even then, praise was sparse.

Casamayor got the call about the Campbell fight and HBO opportunity on Christmas day as he was watching his children open their gifts, and a few days later he was back in Van Nuys at the Ten Goose Gym. He would say in a later interview that he only trained for three weeks for the Campbell fight, but there was only about four weeks separating the Campbell fight from his win over Vargas. In other words, it was known going in that they were short on time.

Goossen was vocal about Campbell’s chances, remarking in a pre-fight interview with Fiona Manning of La Prensa, “He’s a vicious puncher, knocked a lot of guys out. I’ve seen bits of his fights. I was in Florida two years ago and we were on the same card as him. I can’t even remember who he was fighting but I thought he was going to get knocked out and I remember being impressed that he turned it around and stopped the other guy. He has some knockout power but from what I saw, he takes a lot of punches. … HBO must think highly of Nate Campbell to put him in the ring with my guy but I don’t know. Joel is just one of those special fighters. We’re expecting a tough fight from an undefeated guy. I hope he’s prepared for Joel. That’s all I can say.”

During the same gym visit and interview, Casamayor said, “I have had to fight for everything in my life. Even my gold medal at the Olympic Games. The Cuban government did not want me to go to Barcelona for political reasons. Then the guy who was supposed to go got hurt and I took the Olympic Games on one week’s notice. When I got there, I broke the guy’s arm — the guy from Morocco who won the silver medal [Mohammed Achik]. The fight where I won gold I broke Wayne McCullough’s right eye socket and cheek bone. I broke three bones in his face to prove myself. I am very sorry for Nate Campbell but I have to break him too.”

From the outset, Campbell’s unorthodox movement and footwork appeared to confound Casamayor. While most fighters are taught to get their lead foot to the outside in an orthodox vs. southpaw match up, Campbell alternated, darting in unpredictably before circling away to his right. In round 1, Campbell scored early with a jab-right hand combination that Casamayor responded to with a forearm to the face inside. But another annoyance for Casamayor was Campbell’s hand speed.

Headbutts entered the fray in round 2, as did a variety of right hands from Campbell — particularly to the body. And after more slight befuddlement by Campbell in the 3rd round, he pinned Casamayor to the ropes and whittled away at his body with thudding punches, slipping in an uppercut and right hand every so often. Halfway through the round, Casamayor found success in countering with his long southpaw left, but still had to weather the incoming to do it, and an abrasion on his left cheek was worsening slightly.

Between rounds, the HBO microphones caught a humorous exchange: Goossen instructed Casamayor to work more when he got Campbell on the ropes, before referee Pat Russell walked to the corner to warn against Casamayor using his head and forearms. HBO commentator and boxing personality Larry Merchant spoke moments later, saying, “Get the fuck out of here,” before narrating a slow motion clip of Campbell timing Casamayor with right hands.

Casamayor’s left hand was becoming more and more effective each round, but it wasn’t until round 4 that he found a way to land it without eating more Campbell right hands than not. The scrappy Floridian made Casamayor work for the round, however, and landed a number of sickening right hands to the body of the Cuban before the bell rang.

In the 5th, Campbell’s inexperience appeared to be hurting him, as he had few answers for the veteran tricks Casamayor brought; the hand-fighting and upper body movements that put Casamayor into position to land weren’t recognized, and Campbell was hit by punches he didn’t see. Campbell’s right hand stemmed the tide temporarily, but Casamayor continued his surge until the bell. Campbell upped his movement at the start of the 6th, though, and again frenetically bounced punches off Casamayor before being cut by a headbutt over his right eye. Casamayor seemed to catch up thereafter, dirtying up the action to his liking, but again while eating right hands to the body.

Campbell had all but stopped throwing the straighter right hand that he’d been effective with early in the fight, and Casamayor continued beating him to the punch and countering well with his left hand straight through Campbell’s arcing swings. With perhaps the first straight right he threw, Campbell sliced open Casamayor’s left eyebrow with a counter halfway through round 7, though the cut was ruled to be by a headbutt. Campbell blunted Casamayor’s offense with movement and his jab for the last half of the round, prompting Goossen to have Casamayor press.

The pace slowed in round 8, which seemed to favor Campbell’s jab and movement, but Casamayor trapped him and landed just enough left hands to seriously contest the round. In the 9th, Campbell’s first few attempts at landing his right hand were countered by Casamayor’s left, and Campbell was put on the defensive for sequences, though he was very much present with his offense as well. Casamayor’s hard left counters that were eye-catching, though, and erased some of the doubt that his quickly swelling left eye manifested.

Both corners urged their charges forward, demanding the final round for their respective fighters. Instead, both men appeared jumpy and unwilling to give up much ground, and both landed sniping pecks from the outside here and there. A volley from Casamayor halfway through round 10 briefly put him out ahead, but Campbell retaliated with enough right hands to swell Casamayor’s left eye even more before the final bell.

As the two embraced a few moments after the fight ended and souls flooded the ring, both expressed confidence in winning on the cards. But when the first score of 98-92 was announced, a look of incredulity fell upon Campbell’s face, and he deadpanned through scores of 97-93 and 96-94, all for his much more experienced opponent.

The Pechanga crowd apparently disagreed with the decision.

After the bout, Campbell said, “I was never knocked off track. The world saw me win. He was supposed to be the baddest guy in the division. But he was the one who went to the hospital when it was over. I came in and I spanked him. Dan Goossen was the promoter of record. His brother, Joe, was Casamayor’s trainer. I lost a close decision. You figure it out.”

Reflecting a few months later, Waldrop said, “He just didn’t get the call. It’s bad. Nate clearly won the first few rounds. He just blanketed Casamayor. And by all counts, everybody gives Casamayor the fifth, sixth and seventh. Then, Nate comes back in the eighth, ninth and tenth. It didn’t hurt him professionally. I think it gave him a ton of experience and his stature rose as far as being a true bona fide contender.”

Helping Campbell through the difficulty of coping with his first professional loss was a $150,000 purse — a far cry from the $400 he got for his pro debut.

From ringside, Ivan Goldman of Ring Magazine wrote, “If the Marquis of Queensbury were to return from the grave and watching Cuban defector Casamayor for just three minutes, he would wonder whatever happened to his rules. The southpaw uses his head, elbows and forearms as natural components in his repertoire. Casamayor, whose only loss was a close, disputed decision to Acelino Freitas a year earlier, had made his mark as one of the two best junior lightweights in the world. But Campbell, stepping up in class, nearly pulled off an upset in a close contest with plenty of action. By its end, both fighters were marked and bleeding.”

For the most part, Casamayor and his team acted as if the win was business as usual, setting sights on a rematch with Freitas rather than with Campbell. While setting sights high wasn’t a new concept in boxing, the reality was that Casamayor made it through a difficult fight by wider-than-deserved scores and wanted to move on with his career.

Casamayor and Campbell both waded through struggles and losses — often to fighters seemingly below them in class — but picked up the pieces just enough to be in a position that a rematch made sense in 2008. After losses to Diego Corrales and Jose Luis Castillo, Casamayor usurped the lightweight throne in a controversial rubbermatch win over Corrales in 2006, then even more controversially defended the titles against Jose Armando Santa Cruz in his only fight of 2007. In early 2008, Campbell defeated Juan Diaz, who had collected the remaining lightweight belts as Casamayor opted to sit out and wait for a better payday.

The rematch never came.

A stoppage loss to Juan Manuel Marquez later in 2008 appeared to expose the 37-year-old Casamayor’s weakening legs, and he would fight four more times, losing to Robert Guerrero and finally Tim Bradley in 2011. After the Bradley bout, it was reported Casamayor tested positive for marijuana, and to date he has not fought again.

Campbell lost his lightweight belts on the scales, failing to make 135 lbs. before receiving a fortunate decision against Ali Funeka in 2009. Oddly, Bradley also more or less ended Campbell’s career too, as a cut halted their bout early in August of 2009, and he never appeared to bounce back. Fighting 10 times since 2010, Campbell has gone 4-6, opting out of fights early twice in 2013.

It was fitting for a sport full of things that could have been, and greatness that should have been cemented, but wasn’t — a sport full of broken dreams, even if victories along the way kept the fight going.

The unfulfilled potential in both Casamayor and Campbell is perhaps amplified by a rematch between the two that simply made sense, but was just never made.