Boxing’s heavyweight division is its own beast. These days, that beast is looking toothless and dreary, but in days past it was ferocious.

There are no quick fixes, or simple answers as to how or why things change, we just know that the landscape of the heavyweight division now is mostly barren. American networks have been reluctant to even broach the subject of airing heavyweight boxing in recent years.

Long gone, it would seem, are the days when you could turn on your basic cable-only television set on some-odd day of the week, and catch any fight, much less a heavyweight one. Even rarer: a heavyweight fight that isn’t for a major belt.

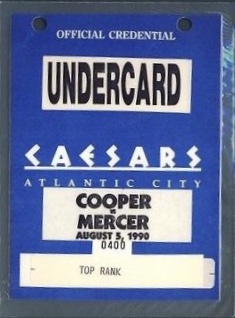

On Aug. 5, 1990, Ray Mercer had it out with Bert Cooper in the first big test of his professional career.

From Jacksonville, Fla., Mercer was born into a military family, as his father was a sergeant in the U.S. Army for 20 years. Mercer attended high school in Augusta, Ga., before playing football at a high school in Hanover, Germany. Upon entering the Army himself, Mercer joined the infantry and became a TOW gunner, stationed in Germany.

It was a twist of fate that brought Mercer into boxing. At 22 in 1983, a super heavyweight fighter also stationed in Baumholder needed a sparring partner, and Mercer was given the choice of helping out in the ring, or going on a difficult month-long assignment in the snow.

Mercer won his first 13 bouts fighting for the Army, then fought mostly in European tournaments under the Army’s banner. In 1985, Mercer notched one of two wins for his team on a U.S. vs. U.S.S.R, boxing show in Troy, N.Y., and he then tried out for the Olympic boxing team. The team’s assistant coach at the time, Hank Johnson, said of that venture, “There were more important things [to Mercer]… A boxer has to be true to his sport. You can’t be missing bed checks. You can’t be going to clubs.”

There were extended breaks and vacations from boxing, with Mercer not fighting for almost a year a few times, but in March of 1988, Mercer struck out to have one heck of a year. He had contacted Ft. Bragg asking for a transfer, so he could train more seriously under Ken Adams and Hank Johnson, and it paid off.

After winning the U.S. Championships in Colorado Springs by defeating Jerry Goff in the finals, he lost a close 2-1 decision to Cuban legend Felix Savon.

The point at which Mercer really seized 1988 was at the Olympic Trials, again in Colorado Springs, in June. In defeating future professional foe Tommy Morrison and former victim Charlton Hollis, Mercer did perhaps what was expected. But when Mercer shut out heavy favorite Michael Bentt, he opened some eyes.

Bob Spagnola, manager and member of the Houston Boxing Association, said, “I thought Michael Bentt was the best amateur heavyweight in the country and Mercer showed him no respect whatever.” And then Mercer went on to defeat Bentt again in the box-offs.

LA Times reported Earl Gustkey openly opined that Mercer showed enough know how and ability to challenge Mike Tyson one day, though trainer Lou Duva disagreed with him. Trainer Manny Steward and Olympic coach Pat Nappi remained hopeful, however. But when Mercer cruised through the first three rounds of the Olympics in Seoul, Korea, the idea that a new heavyweight prospect was on the brink of smashing into the professional ranks became clear.

At 27, Mercer took home the US’ second gold medal at the Olympics by defeating Korean favorite Baik Hyun-Man, who sported long sideburns and was taken out by a left hook nobody knew Mercer even had. In fact, after the fight, Mercer told reporters he had just learned how to throw a left hook weeks earlier.

With a final reported tally of 64-6 in the unpaid ranks, Mercer spent a few months out of the ring, but picked up pace, knowing he was short on time compared to most Olympic champions. In the span of about one year, Mercer brought his professional record to 9-0 (8 KO). There were rumors about bad training habits as Mercer’s weight slowly gravitated away from the the svelte 201 lbs. that earned him a medal, but he kept winning, earning alphabet recognition for defeating former cruiserweight champion and heavyweight title challenger Ossie Ocasio.

In matching Mercer against Bert Cooper, the hope was that the then 15-0 (11 KO) Mercer would pick up Cooper’s minor belt, and shut a mouth or two in the process.

Cooper, born in the borough of Sharon Hill, Penn., caught on to the fight game much earlier than Mercer. He hung out with “Smokin'” Joe Frazier’s son Marvin, and nephew Rodney, who were both accomplished amateurs, having both won the state Golden Gloves in Penn. Marvis was also the national Golden Gloves champion at heavyweight in 1979, and both trained out of Frazier’s North Philly gym. It was the same gym Cooper would travel to every day since the age of 12, to learn how to fight.

Whatever it was that rubbed off was enough for Joe Frazier to hail Cooper as his “adopted son,” and Cooper began emulating Frazier’s style. A short amateur career led Cooper to a 9-1 record, but he had already become known as “the next ‘Smokin’ Joe'” around Philadelphia. Like Frazier, he was small for a heavyweight, both in height and frame, and relied on aggression, amplified by a sweeping hook, to do much of his damage.

In about one year, “Scam Booger,” as Frazier called him, posted a 10-0 (9 KO) pro record. But Baltimore heavyweight Reggie Gross seriously derailed Cooper in their Atlantic City bout, claiming an upset win by TKO. Said Gross afterward, “I knew I was behind, but I knew he was tired. It’s my strategy to wait until guys tire out and finish them off.”

Indeed, one of the judges’ cards had Cooper winning every round, while the other two gave Gross one round, and the way in which Cooper bowed out was strange. Cooper would say much later, “I thought I won every round until he thumbed me in the 8th round.” But considering what Cooper’s track record would go on to reflect, it might be difficult to believe him. It would soon become obvious that one never knew which Bert Cooper to expect on a given night.

Managing to string together six more wins was Cooper — and his two most impressive to date, to boot. First, he defeated 1984 Olympic gold medalist Henry Tillman, who had not yet experienced a loss, and he then left Saskatchewan native and 1984 Olympic silver medalist Willie de Wit in a bloody heap in his own backyard, in under two rounds.

He was still young and learning, though, and Carl “The Truth” Williams looked good against Cooper in June of 1987, despite coming off a bruising stoppage loss to Mike Weaver. After going down in round 1 and absorbing rough punishment for another six, Cooper retired in his corner. In his defense, he gave up a considerable amount of weight to Williams, and had been fluctuating between the cruiserweight and heavyweight divisions since his amateur days, but as time passed, he started looking more like an Average Joe than Joe Frazier.

It would later be revealed, however, that the Williams fight marked the moment at which Cooper’s long-time demons — cocaine and alcohol — exercised eminent domain over the fighter’s soul. And when the drugs’ talons grabbed tighter, Frazier made an exit, leaving Cooper to be managed by Lenny Shaw.

In his next six fights, Cooper went 4-2, but the losses came at the hands of one opponent few knew much about in Everett “Bigfoot” Martin, and another whose only claim to fame was a Penn. state amateur title in Nate Miller. Gone was the promise, as Cooper knew he was at best the number two scrapper out of Philadelphia in two divisions.

For whatever reason, losing to both Martin and Miller in just over six months meant Cooper was a prime candidate for a comebacking George Foreman, and the two were set to meet in Phoenix, June of 1989. And regardless of what actually happened, Foreman walked away with an easy stoppage win, as Cooper stayed on his stool after two rounds of body work and flailing shots from Foreman. But to compound matters, Cooper’s post-fight urinalysis came up positive for cocaine and two other undisclosed banned substances. Now, Cooper was losing not only fights, but good will.

Cooper tried to deflect the blame onto Archie Moore, Foreman’s trainer at the time, charging the former light heavyweight great with hiring two identical twin sisters to party with Cooper for three days straight, thereby ruining his chances at beating Foreman, who had been teased for looking portly in his comeback.

As most would expect, a two month stint in rehab did little to take away Cooper’s dark appetite, and he gained weight. Only once after the Foreman fight was Cooper able to get below 214 lbs., in fact, and it had slowed him down some.

A nearly meaningless win followed by a no decision bout closed out 1989 for Cooper, but in February of the following year, he tabbed a stoppage win over fellow cruiserweight/heavyweight betweener Orlin Norris. And it set Cooper up as a kind of litmus test for a young prospect named Mercer.

It was reported in various news outlets, like the Philadelphia Inquirer, that Mercer was to meet with Tyson in September if he was successful against Cooper, but the time table for that bout was all wrong, apparently, despite the built-in narrative that Tyson had just defeated another gold medalist in Henry Tillman. Regardless, it was a narrative going into the bout.

Ironically, Cooper’s co-manager Lou Silver had prematurely announced that his charge would be fighting Tyson in his first comeback bout after losing to “Buster” Douglas.

Mercer trained at the Triple Threat Gym in Newark, N.J., alongside fellow Olympians Al Cole and Charles Murray, and under the management of Marc Roberts, who built the gym and signed all three fighters around the same time. But Cooper had bounced from trainer to trainer, manager to manager, prompting litigation between managers and promoters, and mysterious trips to Miami for Cooper.

Excommunicated from the Frazier family circle, Cooper wasn’t spoken about kindly by most who had a voice, going into the fight. From being labeled “a quitter” to “totally shot,” Cooper was counted out. His own foe seemed to have him pegged, saying, “I know for a fact he gets tired after three rounds. I know he’s a quitter. There’s nothing really impressive about him. He’s a good fighter. I’m not taking anything away from him. But from a fighter’s point of view, I just look at him like I’m going to get in there and whup his ass.”

For some reason, a shout was made in the Augusta Chronicle about the fact that Mercer was to be announced as being from Augusta, and not Fla. Mercer’s parents resided in nearby Hephzibah, Ga., and Mercer was supposedly hoping to sell a local bout there in the future.

Before the bout, when asked about his alcohol issues, Cooper replied, “I’m not drinking anything stronger than Gatorade now.” Mercer said via news wire, “It’s going to be a good fight for as long as it takes. I wouldn’t go out and get any popcorn because it’s not going to last that long.”

Robert Seltzer of the Philadelphia Inquirer likely summed up the stakes of Mercer-Cooper best: “…when Ray Mercer and Bert Cooper step into the ring today, the bout will represent more of a contrast in careers than in styles. Mercer has a future with promise, and Cooper has a past with promise unfulfilled.”

At the bell, Cooper tore forward, ripping hooks and pushing Mercer backward, before introducing ambidextrous uppercuts — one of which cut Mercer’s mouth — not long into the contest. Cooper’s audacity appeared to get Mercer’s dander up, and the latter landed a 1-2 that sat Cooper down about one minute into the fight. Cooper was up quickly, though, and back to using his cross-arm defense and strength to push Mercer back and landing chopping right hooks before the round ended.

Round 2 began with Mercer establishing a jab, but Cooper wouldn’t have it, and hooks, uppercuts and all manner of full-force punches spilled forth. But while both men were landing well, and despite Mercer’s cut lip, his punches looked to be landing with more raw force, and geographical effect. Cooper hung his hat on a dedicated body attack, which Mercer responded to in kind, but round 3 saw Mercer finding enough separation to rock Cooper at the bell.

Cooper dumped all he could into the 4th round, even bouncing hooks and a few right hands off Mercer’s face while he was being shoved backward. Mercer was present in the action, ready to reply when made to, but he began to slow down before unleashing for 15 seconds straight at round’s end. And once more in round 5, Cooper did well initially before absorbing some clubbing punches. It was clear that the early knockdown was in Cooper’s rearview mirror, though, and he was responding offensively despite a cut on his left eyebrow.

As it had been — and had to — the pace slowed in round 6, following an opening minute that had both men stunned by heavy shots. When Cooper’s eyebrow began to bleed freely, Mercer pulled a veteran move, rubbing his head into Cooper’s eye and tapping with right hands inside. But Cooper took a step back and landed an excellent left hook that stopped Mercer’s assault temporarily. The final seconds that Mercer kept claiming for himself were instead stolen by Cooper, who landed another left hook and follow up flurry that sent him to his own corner smiling through the slight swelling.

More significant was the swelling near Mercer’s right eye, which, coupled with his split lip, demonstrated the cost of war.

In place of bruising activity, Mercer and Cooper turned to more grinding, tussling ways in the 7th round. It was a world of headbutts, forearms, cuffing and four-inch punches, and Mercer didn’t like it, stepping out to chuck bombs for spell before tiring out. But Cooper was the one looking fatigued in round 8, before opening up in the second minute and slamming a series of rights and lefts in to Mercer’s quickly tenderizing mug. Both landed huge single left hooks in the last minute, but Mercer won the battle of leaning. Unfortunately for him, Mercer was also winning the battle of pulverized facial tissue, as the swelling on his left cheek got out of control quickly.

Round 9 had jabs from Mercer, and more jabs, and Cooper was willing to ruminate on them to counter with his own hook, which he landed a few times in the first half of the round. The hook had genuine animosity behind it, and Mercer fought like he noted that. Technique and strategy gave way to more instinctual tussling until the bell, but not before Cooper landed a sizzling right hand on the now-grotesque cheek of Mercer. Cooper, looking to start war anew in the 10th, got what he asked for and more, as a Mercer right hand and resulting flurry clearly affected his legs, but tired Mercer out. Cooper smiled, as he often did mid-fight, and forced Mercer to fight it out.

The swelling on Mercer’s cheek appeared to bother him in round 11, and he was wary of clashing inside with Cooper, so he clinched when he could. But halfway through the round, both men looked for a bailout and exchanged, with Cooper likely getting the worst of it. Win or lose, Cooper was targeting Mercer’s cheek with right hands, being more than just pesky, but not having serious effect.

Mercer heeded his corner’s instructions by staying smart and avoiding mistakes, but he still punished Cooper throughout the final round. A few jabs through the first minute turned into pot-shotting combinations in the second and third, and Cooper could do nothing but reach and find air, or fall into a clinch. Cooper needed to make a statement in the 12th round, and Mercer refused to cooperate.

Though he did enough to earn the unanimous decision, Mercer’s cup lip required 18 stitches, and he wound up with a fractured finger on his right hand and a horribly swollen cheek and jaw. He told Robert Naddra of the Augusta Chronicle, “I’ve never fought anybody as determined as he was. …every time he hit me a good one, my legs didn’t shake. I just went right back and made him pay for it with some good shots. I think I’m at the level now where I can take on anybody.”

He was banged up, but Mercer took home $60,000 and kept his record intact.

Cooper, whose stock certainly didn’t plummet, remarked, “He has average punching power for a heavyweight. I kind of went into the ring cold and that’s why I got caught. I didn’t let it bother me though. I just picked myself up and got right back in.” The subject changed to Mercer’s swelling, and Cooper said, “Every time I hit him, the left side of his face just seemed to get bigger and bigger. [But] he showed he can take a punch.”

If there was a clear positive takeaway for Cooper, he mentioned it. “I proved I can go the distance. I will be back.”

But for the most part, he wouldn’t be back. While the name opportunities continued, so did Cooper’s drug issues. Less than three months after the Mercer fight, Cooper was decked in two by future champion Riddick Bowe, but posted his last significant win in 1991: a surprise stoppage of prospect Joe Hipp on swelling. After that, Cooper’s crowning achievement was knocking Evander Holyfield down for the first time in his career, in a losing performance over the heavyweight title. There was also a thrilling encounter with Michael Moorer for a belt, but Cooper lost that one too.

Before too long, Cooper was losing to any fighter of significance, from ex-champions to future champions; contenders to mere hopefuls. He was in and out of legal trouble, too, including jail time for domestic violence. And before he knew it, Bert Cooper found himself retiring following a 2002 TKO loss to Darroll Wilson, only to come back and fight five more times from 2010 to 2012 — nearly a year after Cooper’s first manager, Joe Frazier, was diagnosed with liver cancer and passed away in 2011.

The win elevated Mercer in the alphabet rankings, despite that Cooper was no longer ranked in any of them. But when an offer came in to face Francesco Damiani for a belt a few months later, his team jumped on it and scored a one-punch KO. A defense in the form of an equally brutal stoppage against undefeated likely superstar Tommy Morrison seemed to again suggest a quick path to a bloody reign.

A shot against former champion Larry Holmes was too good to pass up, and Mercer dropped the belt, but added pounds. Coming in at a career-heaviest 228 lbs., Mercer was befuddled by the former great, and suckered into following him around to the tune of a decision loss. In 1993, a desperate Mercer reportedly attempted to bribe opponent Jesse Ferguson before and during the fight, when he realized he was losing.

Respectable back-to-back losses to Holyfield and Lennox Lewis showed mere flashes of what Mercer could do when halfway motivated. He fought on into the 2000s, losing to Wladimir Klitschko, Shanno Briggs and Derric Rossy, until retiring from boxing in 2008. Mercer tried kickboxing and MMA on for size, but it didn’t last long, and now the former TOW gunner is retired.

Setting aside all that could have been, the possibilities of yesteryear, often no narrative is needed. Title or not, high stakes or gutter, sometimes two men simply meet one another in a ring and throw.