In at least one way, Ruslan Provodnikov, fighting Saturday on HBO, can’t be beat: lovability. He eats raw moose lever, yells “MAMA!” after he wins then bleeds all over her when he sees her, promises to break people “morally,” gets emotional when he thinks of Siberia, recites poetry and watches “Cinderella Man” before every fight… and in the ring, he’s non-stop intense energy. The sports cliche “110 percent” is nonsense, but if there was someone for whom it was plausible, it would be Provodnikov. That intensity forces good fights to happen, since it sucks every opponent into a brawl.

More and more, Provodnikov is hard to beat in the usual way: between the ropes. He might’ve topped a pound-for-pound top 10 fighter in Timothy Bradley if a knockdown or two had been ruled properly. His last fight brought him the best win of his career, over Mike Alvarado. He is a brawler, no doubt about it, but trainer Freddie Roach has harnessed Provodnikov’s hunger to hone him into the best brawler he can be.

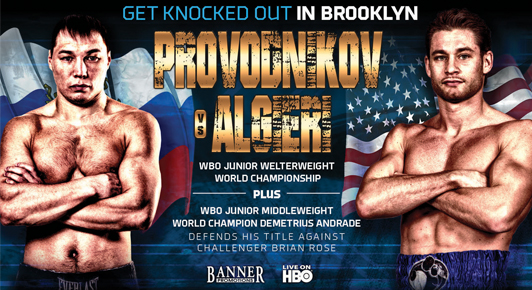

His opponent Saturday, Chris Algieri, hasn’t beaten anyone as good as Bradley or Alvarado had prior to facing Provodnikov, not by a long shot. Like Provodnikov before Bradley, Algieri is graduating to HBO from the farm system of ESPN2 (and NBC Sports) and isn’t easing into any kind of introductory level of competition. Yet the match-up is no gimme for Provodnikov. Algieri is fast, smart, tall and tougher than anyone should be while speaking so openly of his desire not to get hit. He’s about as tempting an upset pick as you’ll find in a situation where the underdog is so untested and the favorite is riding such esteem.

Algieri is more junior welterweight prospect than borderline contender, not that he has ranked very highly on any list of prospects. He’s built himself into a draw in Huntington, N.Y. He’s got a nice story, the fighter with a master’s degree who aspires to become a doctor after his boxing career ends, and he has traditional good looks. What some of that might hide is what a competitor he is. His co-manager told me in an interview last year that Algieri rises to the level of his opposition. The record verifies that. Jose Peralta Alejo last year caused Algieri some issues early; Algieri responded by upping his effort to the point that he threw more than 100 punches in the 9th round. In his last fight, he took relatively easy care of the best opponent of his career, Emmanuel Taylor, and was better than ever. He told me, “Even in training, I want to beat people all the time. I want to win every sprint. I want to lift more, punch more. I like to push myself.”

His speed and length makes him a natural to circle and box from range. His boxing brain, an outgrowth of his college boy brain, means he has some intelligent moves in his arsenal — the double left hook he throws, to the body and then with an uppercut, is not the normal kind. Defensively, he varies things up, sometimes rolling his shoulder to block punches, sometimes keeping a high guard and switching directions with his legs. He is not above clinching in close so he can reestablish himself on the outside. But he also sometimes drops his hands and doesn’t do much with head movement. He’s vulnerable to being trapped on the ropes here and there, although against Taylor he was more adept at escaping than against Alejo, and can be caught with punches while moving in or pulling back out. He doesn’t punch all that hard, some of which is about commitment, because he can do damage when he sits down and isn’t thinking about getting away right after throws. And Alejo rocked him in the 5th round, not that he has a habit of that that I know of.

The two losses on Provodnikov’s record happen to come against the best boxer-types he has faced. Both were close fights, the Bradley and Mauricio Herrera losses, but both also were against men more willing to mix it up than Algieri is. Bradley got dragged into a brawl with Provodnikov; Alvarado had half a hankering to box, and ended up in a brawl. Neither were big on clinching. The pressure Provodnikov applies is severe. He closes in like a vice grip, walking his opponents into hooks from whatever direction they’re fleeing. He isn’t shy with the body punches, either. The reason he’s become a more effective brawler under Roach is that he no longer gets hit so easily coming in, and he’s made better use of his jab. He also trains like a maniac, to the point that for the Bradley fight his urine turned black. And he feels strongly that he got better thanks to the confidence boost he received from that showing. He probably did.

It is surprisingly easy to imagine Algieri outboxing Provodnikov from the outside and shamelessly holding when Provodnikov gets close. Algieri, too, is sure to be better against Provodnikov than he ever has been. But the other outcome is slightly easier to imagine. Algieri has cited his sparring with big punchers Marcos Maidana and Brandon Rios as evidence of his ability to hang with hard hitters, but sparring is sparring and when the headgear’s off and the gloves are smaller, it’s a whole different feel. Provodnikov is going to put more pressure on Algieri than the somewhat tentative Taylor and aggressive Alejo did. And if Provodnikov catches Algieri with the kind of hook Alejo did, Algieri won’t still be standing. Expect Algieri to outbox Provodnikov early while suffering meaningful harm, and for Provodnikov to either catch him with something that takes him out in the middle rounds or for the tide to turn and Provodnikov to wear a too-tough Algieri down for a late stoppage. It’ll take a very impressive performance to make Provodnikov a “must” opponent for friend and Roach stablemate Manny Pacquiao, and I expect Algieri’s movement and boxing ability to leave Provodnikov just short of such a designation.