Somewhere it is written that sons will suffer the sins of their fathers. And I don’t think anything reflects the wisdom of the ages better than the sport of boxing. In this, I’m not saying anything particularly new. Just read Mark Kriegel’s excellent sports bios and his most germane to the sport of boxing, “The Good Son: The Life of Ray ‘Boom Boom’ Mancini,” and it will be made clear that boxers see their trainers as fathers, and more often than not, their fathers are their trainers, which amounts to a sticky situation indeed, considering the brutality of the sport. Perhaps the “sweet science” is a euphemism just for this purpose.

The fact is most come to boxing not for the fun of it. Rather, they are beaten or escape into it. The two are really not that different, as I will show. Boxing provides a supra-structure of discipline where trainers, these fistic father figures, exact said discipline onto boxers who have little chance of receiving structure anywhere else, certainly not from themselves.

Because of this, much has been rightly said concerning the near mythological importance a trainer has for his fighter, but boxing writers don’t take hardly as much time to qualify the shaping of these trainers themselves, and to estimate how much they too are within a paternal structure, a son as much as a father.

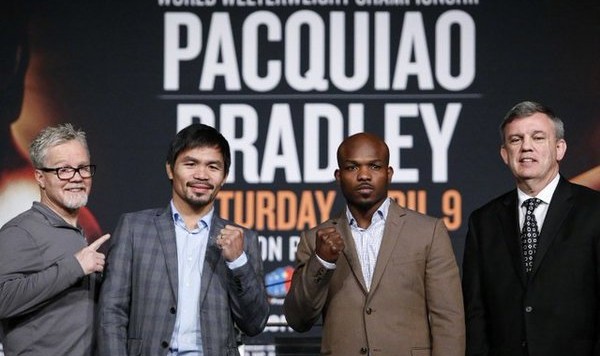

The reason I bring this up is the fight that’s on tonight (Pacquiao vs Bradley 3) and all the talk about who-said-what-about-whom concerning the two Hall of Fame trainers in Teddy Atlas and Freddie Roach.

To be honest, I really don’t care about the specifics of name-calling. This is boxing after all, and styles make fights, even the styles of the trainers, which the smack-talk is really about.

******

Freddie Roach was born of an Irish boxing family in Dedham, Massachusetts. He had his first fight at 6, did his first tournament at 8. He fought in over 200 amateur and professional fights and was once eighth in the world as a lightweight contender by one ranking. Later, as a trainer, he shepherded well over 20 world titlists into the ring. But his story is not so neatly told.

Roach came into this world with boxing gloves on; he had little choice who he was going to be. His father, Paul, a former amateur champion, decided that for him. Freddie would have to forego playing with friends on the playground for going to the gym to fight.

You know the story, a boxing story.

Now as a man of 56 who suffers pugilistic Parkinson’s, the tremors of which are daily reminders of the game he had no choice in playing (and we all know boxing is no game), Roach is perhaps the most successful if not the most moneyed trainer there ever was. Yet he has no wife and no children to spend it on. His only family: his stable of fighters. The Wild Card.

A few years ago HBO’s Real Sports ran a feature on Roach who was then 49. In the piece, the interviewer speculates whether or not Roach’s bachelorhood is a product of his contentious relationship with his father. Freddie’s reddening face affirms this and soon the trainer of the mega-star that was becoming Manny Pacquiao relays that the last time he saw his father was at one of his fights. His last fight. The one he lost.

“I go to the dressing room after the fight,” Roach explains to Real Sports, “and my dad comes up to me and says, ‘What happened? How could you go from being so good at one time, to this?'”

Roach just barely holds back the tears. His voice gets funny. He then reports: “I told him to go fuck himself.

“He kinda gave up on life after that, and he died—of a heart attack or something like that, but I never saw him again.”

******

Teddy Atlas grew up on Staten Island, the son of a tireless doctor who made house calls at all hours, often pro bono. Because of his selfless work, however, Theodore Atlas was not around as much as young Teddy Atlas needed. So Atlas ran wild.

As he himself explains in his 2006 book, “Atlas: From the Streets to the Ring: A Son’s Struggle To Become a Man,” there was a method to his madness: he was looking for trouble, to get “sick” enough so he could finally receive a doctor’s care, his father’s

But of course Teddy didn’t land into a hospital but into another institution: a prison, Riker’s Island, one his father knew not of. There he listened to airplanes take off just outside, long before he ever heard the name Mike Tyson.

Somewhere along the way Atlas realized there had to be a better way. His prison stay and the 007 flick blade that flapped open his face and left the emblematic scar that runs from the top of his skull to his jaw were enough for a young Atlas to join his friend Kevin Rooney up in Catskill, New York where Rooney had been boxing under a guy by the name of Cus D’Amato.

Although Atlas says he was knocking everyone out in the amateurs, soon he had to quit fighting because of scoliosis. D’Amato, a father figure of the highest order, gave Atlas new life as a man and then as a trainer, and created “the young master,” the one who for four years taught MTyson how to box. Throughout his seven-year tenure with Cus, Teddy was never paid. In fact, he had to pay to stay in Catskill. Well, that’s not true, his father, the doctor, paid.

***

At first blush, the demonstrative, authoritative Atlas is worlds apart from the soft-spoken, Roach still boyish at 56. But they wouldn’t both be in boxing for as long as they have if that were true.

Freddie may never have been a family man like Teddy but he certainly came to be the patriarch of The Wild Card Gym and the most well-respected trainer of the last twenty years, interestingly about the time Atlas stepped down from the corner and got behind the microphone. Perhaps this is part of the problem, part of the animosity between the two. There can only be one father.

With Timothy Bradley’s demolishing of Brandon Rios this past November, surely “The Desert Storm” made claim to a new trainer, if not a new “father.” Although no longer young, the 59-year-old Atlas proved ever the master.

The same man who took a scared kid from Brownsville who used to hide between abandoned buildings to the verge of greatness in the sport of boxing as well as the same man to bring Michael Moorer and Alexander Povetkin to heavyweight world titles. (The title, by the way, that Moorer won from Holyfield in 1993 came shortly after the death of Atlas’ father, for which Atlas in his book attributes to his father looking out for him.)

I’m not sure if Roach attributes his success to his father but based on that Real Sports interview he knows for sure he wouldn’t be in boxing without him.

And so they in boxing styles make fights. But this one is hard to call. Seems Teddy and Freddie come up about the same.

(photo via)