“And so it is those we live with and should know who elude us. But we can still love them — we can love completely without complete understanding.” – Norman Mclean

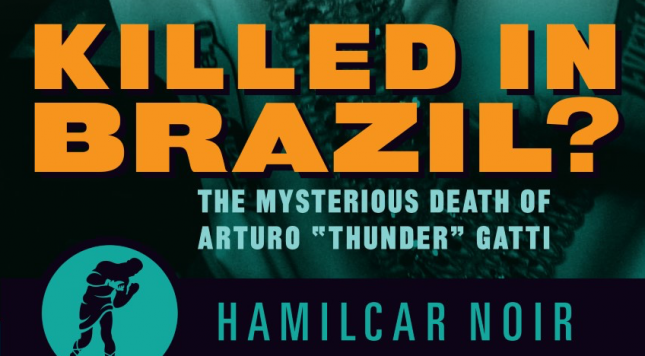

If ever existed a fighter who was loved completely, it was Arturo “Thunder” Gatti. Beyond being loved, he was mythologized because he knew what part of himself to give, that it was wanted, and because he always gave completely of himself. Very few of us can say the same of our lives and fewer still can say it of their life’s work. In Killed In Brazil? The Mysterious Death of Arturo “Thunder” Gatti (Hamilcar Publications, $10.99), author Jimmy Tobin removes the shroud that has surrounded Gatti’s life and death.

The book begins with the boxer’s death in 2009, in Pernambuco, Brazil. Tobin deftly reconstructs the events leading up to Amanda Gatti finding her husband’s lifeless body, and the maelstrom that broke loose in the aftermath. More history than whodunit, the competing perspectives of family and friends and Amanda Gatti herself are weaved together by the author through contemporary accounts and interviews, so that as events unfold we learn not just what happened but how it felt to those involved. How the reader should feel about those very same people is left up to them. These aren’t characters; they are human beings. And at every turn of the chaos between Gatti’s death and second autopsy, we are reminded of how, when confronted by tragedy with no clear answers, we often substitute faith for fact.

To understand how Gatti went from man to myth, Part II of Killed in Brazil? explores his career in full. The fights that packed Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City and made Gatti a headliner on HBO are retold in thrilling detail. Of Gatti’s 1997 match with Gabriel Ruelas, “he halted his retreat long enough to unload a big left hook that got a tiny stumble out of Ruelas. Ruelas turned unsteadily, opened his arms to Gatti, inviting attrition, and charged. Bleeding under his left eye, Gatti welcomed his opponent’s presence, knowing his target by feel. He sunk body shots and left hooks into Ruelas, but Ruelas was undeterred, accepting the immolation that might make amends for Jimmy Garcia.”

Tobin’s prose, and by extension his storytelling, is elegant and nuanced. There is a self-possessed economy of words that finds its force by being completely true to itself and its subject. Tobin has shown Gatti the ultimate respect, and compassion, by treating him as a man, noting of one of his arrests, “just as new vistas cannot free you from the troubles of your mind, so did Gatti fail to escape his demons in the ring.” The drive that can allow you to survive and thrive in dark places can also take you back to them against your will.

Killed In Brazil? becomes fully itself in Part III, which details the independent investigation into Gatti’s death and the civil trial over his will between his family and widow. We are assured by Gatti’s friends, family, manager and promoter that Gatti did not commit suicide because, quite simply, he couldn’t. The independent investigation into his death, commissioned by manager Pat Lynch, is scrutinized carefully and thoroughly. If you are not one of the people directly impacted, it will likely leave you with more questions than answers. But when something has to be true, anything that might contradict it can be ignored or rejected. So despite those closest to Gatti knowing that he had a history of depressive fits, worsened by drug and alcohol use — including threats to kill himself — it is impossible to allow that it was possible.

Tobin also raises the specter of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, though more for perspective than speculatively. It is impossible to know if Gatti suffered from CTE, but he showed behavior consistent with the condition. This section also pays special attention to the psychology surrounding suicide and its effect on those left behind. To understand Gatti’s death, the reader must understand Gatti, as well as the people closest to him.

The book, and Part III, end where Part II began — with Gatti’s children. We are gently reminded that more important than adults needing to be right, to make sense of tragedy and their own pain, are two children named Sofia and Arturo Junior, who will only know their father through the lens of others’ reminiscence and the films of his fights. Beyond the mystery, lawsuits, autopsies and press conferences, two small children lost their dad.