Boxing is a sport both immensely empowered by, and hamstrung by, its past.

Its past dates back to at least the 8th century BC. Even now, the most important sporting figure of all time might just be Muhammad Ali. For much of the last century, the biggest-name boxer alive was often in contention for biggest name in sports period; who else could contend with Michael Jordan in the 1980s but Mike Tyson? This storied history means that when someone truly achieve something that stands out, it has to have stood out against its entire mythology. Modern boxers striving for greatness compete with legends. Eclipsing them makes a boxer in to a legend themselves. That’s enriching.

At the same time, boxing is competing with its past in another way: In the imaginations of sports fans today. Former boxing fans of past generations — “generations” is a loosely used term here — might say they lost interest once Tyson left. Around a decade ago, someone might have said, “I don’t know anybody anymore since Oscar De La Hoya left.” Ask them a little later, and they might have said, “I don’t know who’s fighting now that Floyd Mayweather’s retired.” Today, someone might say the same thing, but odds are good they’ve heard of Manny Pacquiao.

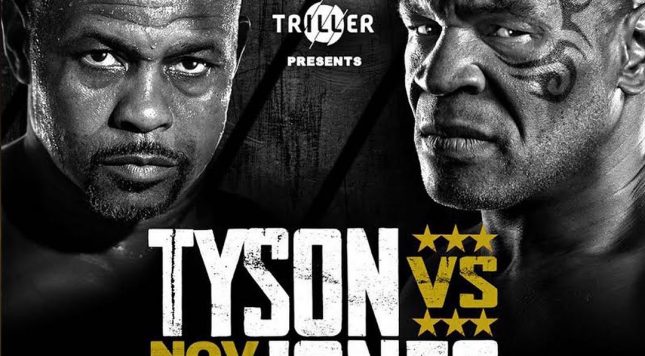

It’s how we get into a situation where Tyson vs Roy Jones Jr and Manny Pacquiao vs Conor McGregor are sucking up so much oxygen in the mainstream media and in the minds of casual fans.

It’s doing so even though the meaningful boxing landscape — defined for our purposes as, “matches between current, high-level pugilists” — is in the midst of a pretty incredible stretch, made all the more incredible by its proximity to the worst pandemic in more than 100 years.

Boxing has a chance to have real champions up and down its divisions over the next few months. It’s just 2020 but the best fight of the this decade, between junior welterweights Jose Zepeda and Ivan Baranchyk, might already be in the books. Next weekend brings one of the best few fights that can even be made in the sport, Vasiliy Lomanchenko vs Teofimo Lopez at lightweight.

Once upon a time, this writer might have lamented that everyone was paying more attention to a full-fledged freak show — two 50-year-olds fighting qualifies, sorry! — and at least half a freak show featuring an aging but still-potent boxer against a fading mixed martial arts star with precisely one professional boxing match (a loss) on his record.

These days, it’s more a shoulder shrug. As Larry David once said when offered a house tour in “Curb Your Enthusiasm”: “It’s OK. I get it.” You enjoy that house and/or boxing freak show. The appeal is obvious, from the outside. But it’s not really something that needs to be seen.

So what’s to get?

There was a year when Jones vs Tyson would’ve been at least a moderately interesting fight on paper. Jones had made an improbable run from middleweight to heavyweight, a monumental 40-pound stretch. It featured a win over John Ruiz, a genuine top heavyweight when they met in 2003. Tyson in 2003 was coming off a drubbing by Lennox Lewis, and everyone knew he was well on his way out, but against a lighter guy like Jones, as opposed to a 6’5″ behemoth like Lewis? Maybe it would’ve been a little something to watch, part freak show sure. But it fell through.

That was 16, 17 years ago. Tyson is 54. Jones is 51.

A common question I hear about Tyson-Jones is, “Why do this? Are they broke?” By available accounts, Tyson was but is no longer. Jones very well could be, although the reporting there is a little more dated. His last pro boxing match was just two years ago, well past when he should’ve ended his career. He’s said he kept fighting for love of the sport. It’s at least questionable how much he loved losing eight times in his last 25 fights, including some vicious knockouts against people he would’ve blown out of the ring prior in a career that had previously suffered just one loss, and that one just a strange disqualification.

Tyson’s case for taking this fight for love of the game rings more true. The transformation of sports’ most frightening villains into the cuddly elderly as the mellow and examine their lives is a tried-and-trued formula, and Tyson has traveled the furthest from “out-of-control terror” to “kind of cuddly?” It doesn’t excuse what he did before, but it’s also clear Tyson is no longer that person. He says he didn’t get to end boxing the way he wanted. It’s easy to imagine him looking at a career-closing loss to Kevin McBride — where he clearly was disinterested in contending and admitted as much — and having regrets.

So what do they have to gain and what do they have to lose?

They’ll surely make a decent chunk of change, and get a little name inflation during a time where the world’s not its usual vibrant self. Even if both are doing well financially, it’s hard to turn down cash doing something that you did better than anything else you did in life. In the best-case scenario, with the extra-large gloves and exhibition rules, they spar a bit, each man looks good for a stretch or two, nobody gets hurt and the crowd turns off the TV satisfied with money well spent.

That’s the plan, anyway. The other other scenario is Tyson’s talk of shooting for broken jaws, etc. is legit, rather than promotional bluster, in which case this could be dangerous for Jones. True, Jones was in the ring at a competitive level more recently, while Tyson’s skills might be rusty, however good he’s looked in recent footage. Jones has suffered too many ruinous knockouts, sadly, for him to take on a full-force Tyson if he has much of his power left. Ideally, Tyson backs off if he sees Jones hurt, as he has before in exhibitions, as he did here at about 1:20.

There’s a middle scenario, which isn’t unprecedented*, where it starts as a bit of sparring that turns real when someone’s competitive juices or pride gets the better of them.

You have to hope that if it’s either of the latter two scenarios, the California State Athletic Commission is ready to pull the plug quickly.

Pacquaio-McGregor is much more in the twilight of each man’s career, rather than deep in the darkness of night. It’s closer to a legit fight, which, of course, is easy to say about just about any fight.

Despite the aforementioned criticisms of McGregor, I was of the mind that his bout with Mayweather was more competitive than expected, in part because Mayweather took a little time to adjust to McGregor’s unconventional style. McGregor has been knocked out once more since, in the sport where he made his name, which isn’t an encouraging sign.

And Pacquiao is still a top-10 welterweight at age 41. Moreover, he’s active now in a way Mayweather wasn’t when he faced McGregor. Pacquiao, too, is less conventional than Mayweather, which means he could give McGregor the kind of fits that he himself gave Mayweather briefly. If anything, this is likely an easier fight now for Pacquiao than it was for Mayweather three years ago.

What it suggests — if it happens — is that both men are more interested in cashing out on their names than they are in competing at the highest level of their respective sports. Or, at least, they’re trying the idea on for size.

And that’s OK, for them. They’re welcome to it. In Pacquiao’s case, he might even deserve it. He’s given us a lot more boxing than anyone might have anticipated, and he’s given a lot of the money he earned back to his homeland. (Let’s set aside what they “deserve” personally, as there’s reprehensibility to had in both of their lives outside the ring or octagon.)

In a boxing utopia, everyone’s flooding to what’s happening with elite competitive boxing today, and maybe are moderately entertained when nothing better’s on by the likes of Tyson-Jones or Pacquiao-McGregor. This is no utopia. Boxing’s history is its blessing and its curse. It simultaneously animates it and calcifies it.