There is no boxing thanks to COVID-19 and we might have roving gangs of warboys before pro pugilism returns. So we TQBRers are looking back at the beforetimes.

“Context matters” is a thing people say because it just does, everywhere, all the time — which is to say, except for when one is talking about context, which matters no matter what. It matters in specific ways for specific things, what with that being the nature of context and all.

In boxing, context matters in at least this way: A great boxing event, like any great sporting event, stands alone free of context; the greatness is plain to see, regardless of whether one has seen a single boxing match at all. You can feel it. You can see it. Most of the world gave zero shits about basketball until Michael Jordan came along, and then you see the guy as close to “literally” flying as we get, and you just grok it.

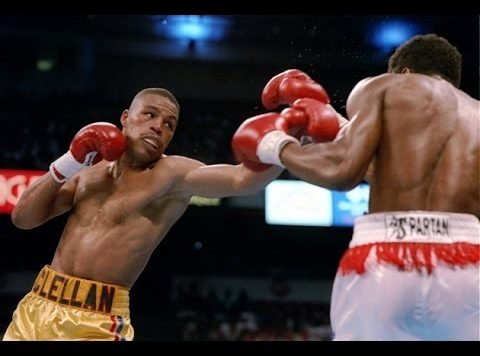

The time when Gerald McClellan and Julian Jackson first met one another probably doesn’t rise to that level. So it needs context. It’s context we benefit from after, too, perhaps more so, one of them tragic.

Ten years after they met, in the year 2003, Ring Magazine dubbed Jackson and McClellan the 25th and 27th best punchers of all time. It’s not like people didn’t know they had two certified cinder block slingers in the ring, and that didn’t change after, either. McClellan secured 29 of his 31 victories by KO. Jackson won 49 of his 55 via KO. But yeah, later, it turns out this fight was more like “watching historical power in action” rather than “a good shootout-to-be.”

Jackson had arrived for the middleweight battle as the 2-1 favorite, the older fighter (over 30 at a time when that meant more than today) with signs of diminishing versus the lesser-proven McClellan (just entering his mid-20s).

But McClellan struck first. Legendary Emanuel Steward knew what to do with punchers: How to coach them, how to neutralize them. McClellan had Steward in his corner, and McClellan had Jackson across from him, so that worked out just fine for McClellan. McClellan, then, went on the attack against the kind of fighter least inclined to fight going backward, and who benefits most when able to generate forward momentum. Everyone knows about this strategy by now. It’s just dumb for most people to try.

Not for McClellan, who figured he was just as powerful as Jackson (close!), stronger (maybe?) and faster (true, or, at least, more nimble, especially with his ring movement). A big right in the 1st nearly caused Jackson, sporting his badass flattop, to drop to one knee.

McClellan started the 2nd on the attack still, what with it winning him the 1st. But Jackson connected with a left hook to the body that McClellan felt so profoundly that it made him motion like he’d been hit with a low blow. He hadn’t. He tried to muster bravery to reengage, but Jackson switched to a left upstairs and McClellan spent the rest of the round in retreat, clearly hurt.

This fight, by the way, never became a wild brawl or an action-packed shootout or whatever. What it was after just two rounds, and what it would remain, was a dramatic seesaw marked by tactical Battleship-style explosions, and somebody was fixin’ to get sunk before long.

The 3rd saw the next dramatic shift: Jackson built on his momentum from round 2 until an accidental head butt left him bleeding, and those of us with the context of having seen this a million times knew what might happen next, which is that Jackson might get flummoxed and McClellan might get inspired by the sight of the trickle. And that’s exactly what happened.

The 4th was pretty much all McClellan. The 5th, though, looked like it might be the kind of round where Jackson would benefit from a foul. Jackson delivered two straight clear, probably intentional low blows, and McClellan needed a break. When he got back up up, Jackson pretty quickly capitalized with a right of the very hurtful variety, the kind of which he needed as few as one to end most fights.

And then arrived the final dramatic swing. McClellan dipped down like he was going to throw a body shot — and both men victimized each other’s ribcages all fight long, so Jackson had to pay attention — and Jackson set up to counter with a right.

But McClellan’s feint had already ended, and he shot an overhand right. Jackson might have gone down anyway, but McClellan wasn’t going to get cocky and do that cool-as-fuck thing Jackson used to do when he saw an opponent drop: stretch his glove straight out and motion downward as if his opponent was a voodoo doll. A leaping left put Jackson down, and nearly out. He got up only for a left-right combo to put Jackson down again.

When Jackson rose again his face was split all to hell, and so was his grasp on consciousness. Mills Lane — whose refereeing judgment was a reminder for this writer about why he was one of the best ever (breaking people an appropriate distance, giving timely warnings) — made the right call that Jackson wasn’t ready to continue.

McClellan had arrived.

Sadly, here’s where the tragedy kicks in, too. After this fight, McClellan began complaining of frequent headaches. Four fights later, McClellan’s boxing career would end with him being stretchered out of the ring. In a sport that leaves some of its participants ravaged, McClellan’s condition is one of those cases that nearly pierces the notion that someone can be a good person and enjoy boxing simultaneously.

(photo via)