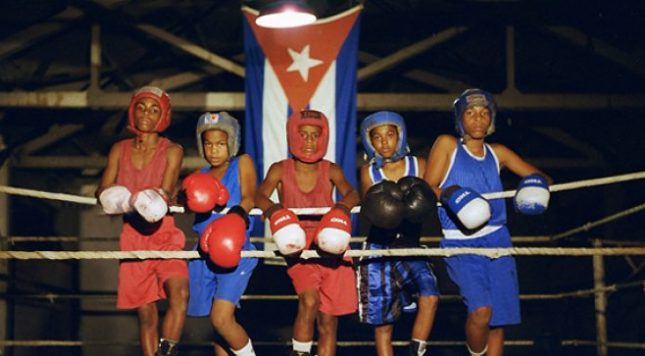

Few countries boast as proud an amateur boxing tradition as Cuba. The island nation has won 73 Olympic medals in its history, including 37 gold, despite having boycotted the Games in 1984 and 1988. Many of Cuba’s most successful amateur boxers chose to remain in their country, where professional boxing has been banned since 1961, instead of leaving to turn professional. They chose to stay loyal to the Revolution that enabled them to become elite athletes and stars. But there are always exceptions to any rule, and some talented Cuban fighters took an enormous risk to defect in the hopes of achieving the type of financial success that would never be possible in Cuba.

The Cuban style of boxing heavily emphasizes counter-punching. It’s about letting your opponent lead so you can capitalize on their mistakes. “The Cuban boxing style centers around a choice in the calculus of fighting; that it is a much more intelligent position in terms of your longevity and your chances of victory to be a counter-puncher,” explains Brin-Jonathan Butler, who is an authoritative voice on Cuban boxing, having spent eleven years living and training there, much of it under the tutelage of former two-time Olympic champion, Hector Vinent.

Butler makes an apt comparison to the world of chess in that nobody wants to lead the dance. “In Cuban boxing, you want to limit your risk at all costs and make the other person screw up because that’s the most efficient, strategic method to victory.”

Although that style doesn’t always lead to exciting fights, Butler is quick to point out that painting all Cuban fighters with the same brush is not only unfair but inaccurate, given that some of the nation’s greatest fighters were explosive and capable of producing electrifying knockouts.

“There’s this perception about the Cuban style that I don’t think matches up with a lot of the great Cuban champions,” asserts Butler. “Teofilo Stevenson and Felix Savon were devastating knockout punchers. Look at Felix Savon annihilating David Tua in 90 seconds, destroying Michael Bentt, and knocking Shannon Briggs through the ropes. Hector Vinent had a completely professional style had he gone that route. He was dominant in the amateurs, defeating Fernando Vargas and Shane Mosley. There is a trope that Cuban fighters are boring, robotic, and technical; That they’re not human and don’t have heart. But compare that with the great Cuban fighters and their actual records,” Butler explained.

While it is true that those aforementioned Cuban boxers were more offensive-minded, there are several modern Cuban defectors whose style reflected the “typical” risk-averse Cuban approach. That includes Joel Casamayor, Erislandy Lara, and Guillermo Rigondeaux, who all became world champions but never cultivated a fervid fan base of supporters.

I am not going to say that fighters should take more risks to please the fans because the fans aren’t the ones who have to deal with the repercussions of brain trauma. However, there is something to be said for being entertaining in the ring because that’s what puts more money in fighters’ pockets. As David Greisman explains in his Fighting Words column about Demetrius Andrade, “If people enjoy watching you, then they’ll look forward to seeing you. They’ll buy tickets. They’ll tune in to your shows. That will make you more of a star.”

Although Casamayor, Lara, and Rigondeaux never became bonafide stars, largely because of their unappealing styles, there were a few occasions when they fought out of character and produced thrilling brawls. It is those fights that delivered ample action and entertainment value that are worth highlighting.

After winning gold at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992, Casamayor became a two-weight world champion as a pro, including the lineal lightweight title. It was in defense of his lightweight supremacy in 2008 against the undefeated Australian banger, Michael Katsidis (23-0), that Casamayor put on arguably his most exciting performance. The champion got off to a rousing start when he dropped Katsidis twice in the opening round courtesy of his southpaw straight left. But Katsidis roared back to buzz Casamayor in the 4th, knocked him through the ropes in the 6th, and came close to stopping the cagey Cuban veteran. Casamayor was able to resort to his ingrained boxing skills and movement to regain momentum, which enabled him to score a decisive finish. In the tenth, Casamayor nailed the overzealous Aussie with a looping counter left that badly hurt the challenger and Casamayor’s follow-up flurry forced the ref to step in. At 36, it would be the last big win of Casamayor’s career.

In 2018, Erislandy Lara, 34, took on Jarrett “Swift” Hurd in a junior-middleweight unification fight that was a fight-of-the-year contender. Hurd brought the pressure and forced Lara to fight in the trenches for long stretches as he looked to impose his will and physicality on the slick Cuban. But Lara was effective when he used his legs to move and countered Hurd on his way in. Even when the two exchanged brutal shots on the inside, Lara dished out his fair share of punishment. However, Hurd was relentless in pursuit and he made sure Lara felt his greater size and strength as the fight progressed. It was a close fight that hung in the balance until the last round, when Hurd scored a late knockdown from a left hook. That knockdown was the difference as it gave Hurd a split-decision win, both judges having him up by a single point.

After the fight, Lara said that, “It was a great fight for the fans. I stood and fought a lot and it was fun. I thought I clearly won the fight.” Upon hearing those words, it sounds as if Lara was choosing to fight in a more entertaining manner to appease the fans. But that just doesn’t seem like a viable explanation.

Rigondeaux chanted a similar tune after he engaged Julio Ceja in a grueling phone-booth war in 2019. The two traded vicious power shots from in-close for the entirety of the fight, with barely any respite in the action. It was a howitzer of a counter left from Rigondeaux that ended matters in the closing seconds of the eighth round and earned him the impressive win. But in the process he absorbed by far the most punches he had ever taken in a pro fight. After the contest, Rigondeaux stated that “People were saying that I get on the bicycle and run a lot. Well, that’s not true, so I wanted to show them I could fight at a short distance and I wanted to get a couple rounds in.”

Why would Lara and Rigondeaux care about the fans when they didn’t in the past? What is more likely is that they wanted to protect their ego by refusing to give their opponents credit for making them fight a different style.

“Rigondeaux was quoted as saying that he was always criticized for not fighting in an exciting way and so I’ll show them I can. I don’t believe that for a second,” says Butler. I don’t believe that he would choose to fight that way against a fighter that is not well-known with not much television exposure when he was not willing to do that in his bigger fights with bigger audiences. That Ceja fight showed nothing of the Cuban style so why has he abandoned it at 38 years old? Now he wants to fight in a phone booth when there’s really no upside in doing it. I don’t see how that’s a calculated choice to prove the critics wrong because what’s the point of proving the critics wrong at this stage in the game?”

A more probable explanation for why the trio of Cuban stylists fought out of character in those instances is because of their age and style of opponent. Casamayor, Lara, and Rigondeaux were 36, 34, and 38 respectively and in the twilight of their careers. Not only were they older, but they also had plenty of wear and tear on their bodies due to extensive amateur careers. With heavier legs, they had no choice but to stand in the pocket and fight fire with fire.

It wasn’t just their advanced age and reduced mobility, they had to have the right opponent in front of them. And that’s exactly what they had in Michael Katsidis, Jarret Hurd, and Julio Ceja. All three were aggressive, pressure fighters with sturdy chins that were willing to take two to land one. They knew their identity as fighters and that the only chance they had of winning was imposing their game plans and making the fight ugly. And while Katsidis and Ceja ultimately lost, both of them had their moments, which is what made the fights dramatic.

It would not have been a wise choice for that Cuban trio to completely abandon their amateur style when they turned professional. Had they done so, they likely would have never scaled the heights they reached in winning multiple world titles and racking up numerous championship defenses. Given the exciting scraps that they helped create in later stages of their career, one can’t help but wonder what additional fun fights they could have been involved in had they chosen to take more risks. Still, the fans are lucky there are a few gems involving modern Cuban fighters. If you’re ever looking for a blend of pugilistic Cuban skill and action, look no further than Casamayor-Katsidis, Lara-Hurd, and Rigondeaux-Ceja. Trust me, you won’t be disappointed.

(Photo via)