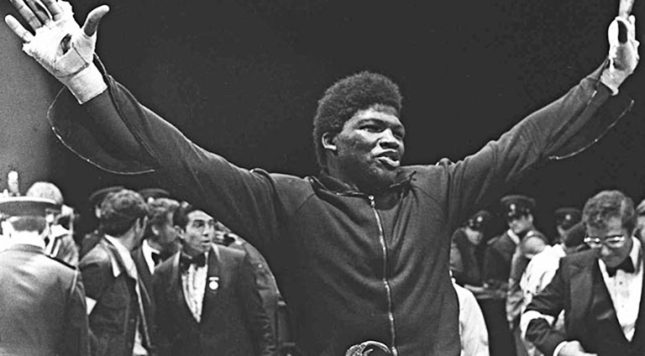

How should we remember John Tate?

We could argue all day about how much control we have over the paths that our lives take, but one thing that we have little control of, is how people choose to remember us. Take Big John Tate, for example.

Two boxing fans are chatting away in a bar…

“What about that 1976 U.S. Olympic team, eh?”

“Yeah, what a team! ‘Sugar’ Ray Leonard! One of the greatest ever!”

“But there were plenty of others too…”

“I know. Howard Davis. Voted best boxer at the Games. Tremendous skill set.”

“What about the heavyweight?”

“You mean ‘Neon’ Leon Spinks? Gold medallist light heavyweight and eventual world heavyweight champion! Along with his middleweight brother, Michael, of course. Two brothers, both gold medallists and later heavyweight champs. Now that is some history there.”

“Too right. But no, I meant the heavyweight from the Games. John Tate, wasn’t it?”

“Of course… I remember. Didn’t he get knocked out in the last round, or something, to lose the title….?”

In the May 1981 edition of The Ring Magazine, the editorial team saw fit to run a poll among the members of their International Ratings Panel to establish who would have the honour of being considered the worst champions in history across the divisions. At heavyweight, that dubious label went to John Tate. He “beat” Primo Carnera handily to claim the top spot.

Boxing surely has more rags-to-riches-to-rags stories than any other sport, so Tate’s downfall is not unusual. Falling from such stellar heights as champion of the world and the hope of million-dollar paydays, to hard times and an early demise, actually puts him in the company of some of the greatest fighters in history. The number of champions who escape from humble beginnings only to return to them later in life should show us how slippery that pole to lasting success really is.

That same May ’81 Ring magazine also contained an article entitled, “What ever happened to Big John Tate?” and his photo adorned the front cover. The article reflected on his February ’81 comeback fight, a 10-round points win over one Harvey Steichen. Steichen had a record of 14-9 at the time, although ended his career with more defeats than victories and suffered early knockout losses to the likes of Frank Bruno and Tony Tucker, among others.

How many heavyweight champions can say they won the title in front of more than 80,000 people in their opponent’s backyard? Big John, who at the time was 19-0, can. Also factor in that the backyard in question was apartheid-era South Africa, against a white South African. The event was the first with an integrated audience, but Tate may well have felt outnumbered when he looked out into the crowd.

Beating Gerrie Coetzee in 1979 for the vacant WBA belt must have felt quite something for a man who had worked picking cotton earlier in his life. Larry Holmes may have been the other titleholder and would go on to prove himself to be a true, and truly great, champion, but at that time both titlists still had work to do to stake a valid claim on the historically richest prize in sports.

Olympic bronze medallist and WBA titlist: It must have been easy to imagine that further glories would follow for the Knoxville man. There was talk of a huge purse against a comebacking Muhammad Ali. However, it was not to be, and it was the events of that fateful year of 1980 that resulted in the esteemed Ring magazine cruelly branding him as the worst of all heavyweight champions, just as he was trying to claw his way back to the top. Talk about kicking a man when he is down.

Being on the front cover of the Ring? Awesome; a fighter’s dream come true. Flick further through the pages and find yourself on top of the “Worst Ever” poll. Not so good.

John was still learning to read as an adult. It’s not hard to imagine him practicing by reading the Ring. I wonder how he felt reading that?

His homecoming first defence against Mike Weaver has its own notoriety as being one of the great come-from-behind KO wins. With just 45 seconds remaining, it was “Big John” who was ahead on the scorecards before Weaver made them irrelevant with a very late knockout victory to take the title. If you happen to be involved in a fight famous for a come-from-behind victory, you don’t want to be the one who is lying face down on the canvas as the fight ends.

Three months later he was in against Trevor Berbick, supporting “The Brawl in Montreal.” While his Olympic teammate, “Sugar” Ray, was warming up to meet Roberto Duran in the main event, “Big John” was still in the fight in the 9th round, before Berbick separated Tate from his senses and even further from returning to boxing’s top table with a couple of rabbit punches. Two brutal stoppage losses in quick succession following a very brief reign as champ, and things were never the same again.

In boxing’s version of the Marvel superhero films multiverse, there’s a timeline of events where “Big John” stays on his feet against Weaver, wins on points and goes on to face Ali for life-changing money. But this isn’t the movies and that’s not how it played out. We have only one version of reality, and one that wasn’t so kind to Tate.

“Big John” boxed on but without ever encroaching on the higher echelons of the rankings, somehow ending his professional career fighting in London, at the famous York Hall, in 1988, and weighing in at 281 lbs. — 40 lbs. more than when he faced Coetzee.

Kellie Maloney promoted that final fight and remembers “Big John” fondly.

“He was a nice guy; I liked him, but you could tell he was past his sell-by date. He still had all the moves and the talent, but he wasn’t in shape. He was a boxer more than a puncher. He was just there picking up the cheque, really. Some of the stories he told me were amazing. That night in South Africa was his greatest moment of glory. Everyone liked him, although we had a bodyguard on him 24/7, just to keep an eye on him.”

“He was a simple guy. A world champion, but with no real education. I’ve got nothing bad to say about him. I felt a bit sorry for him. Boxing is brutal unless you’re the Kingpin.”

Big John Tate was many things, but never the Kingpin.

“Big John” died in 1998 at the age of 43, following the all-too-familiar tales of addiction, financial hardship and crime.

However brief his title reign, and however swift his downfall, Tate did achieve enormous success and reach heights that most of us can only dream of. Yes, his is a story with a tragic end, but to paraphrase what someone once said about Sonny Liston, it is not his tragic end that should surprise us, but the fact that he was even able to climb from working in fields of cotton all the way to heavyweight glory at all in the first place. Those are tough odds to beat.

The worst of the champions is still a champion, and John could call himself champion, albeit briefly.

In that Ring magazine poll, the voting panel consisted of 60 experts. 59 of them cast their votes. England’s Eric Armit was the only one who refused to take part. His reason?

“I have too much respect for any man who has the courage to fight as a professional to put such a label on him. A man is as good as he is – if that’s not very good, then so be it. Not everyone can be a Joe Louis or a Sugar Ray Leonard, but they don’t deserve the insult of being named the worst.”

Well said, Eric.

(Photo via)