After Grudge Match’s genre baiting, we might need a year off to take boxing films seriously again. Hopefully after 2014’s boxer-free film slate we’ll get back to the grit, poverty, powerlessness, and pathos the screen fighter suffers on our account.

The ubiquity of the boxer in film doesn’t always make for the freshest films. New York Times film critic A.O. Scott ranks the boxing film King of Worn-out Tripe in his review of David Russel’s 2010 The Fighter: “With the possible exception of the romantic comedy, no film genre is more strictly governed by conventions — or enslaved by clichés, if you prefer — than the boxing picture.”

True, boxing does feel overused sometimes, but no more than the Boy Meets Girl story or the Courageous Soldier story. It’s easy to mistake archetype for banality, but in good hands they transcend the endless conventions; after all, Achilles’ pouty warrior motif still works from time to time. Roger Ebert put Rocky in his Great Movies pile for the exact reason: “It’s about heroism and realizing your potential, about taking your best shot and sticking by your girl. It sounds not only clichéd but corny — and yet it’s not, not a bit, because it really does work on those levels.”

Rocky’s story is a century of character history in 90 minutes. An impoverished, hardscrabble screwup from a busted neighborhood gets a once in a lifetime shot to be champ. Overdone, maybe, but the layers get more interesting the more of them you peel off.

The bruising void of money and opportunity is the genre’s base. Even robbers and criminals get a break with wealthy Thomas Crownian thrillionaires and suave Daniel Oceans to shake things up, but Hollywood’s boxers will forever be mopping blood in meatpacking plants, hauling banana crates off Hoboken docks, or picking onions in sharecrop fields.

The boxers on screen start the film broke, not just because real world boxers tend towards poverty, but because the boxer’s story is necessarily one of growth. They’ve got to start at the bottom to climb to the top – and in some cases, fall back down to the gutter. The film boxer acts like a kind of barometer for how poverty manifests itself through the decades. For decades, boxing lurked behind the shadow of trench-coated gangsters, then moved on to rural poverty with films like 1978’s Every Which Way but Loose, then into the early 1990s’ crack-ridden blight in the case of The Fighter, and even the Great Recession’s slow, creeping hardship with 2011’s Warrior.

Early on in the 20th century boxing looked like John Garfield’s boxer Charley Davis in 1947’s Body and Soul. Charley starts in sleazy dives, gets big, and ends up spiraling down due to his thuggish affiliations and personal demons. Films like Body and Soul invariably punished the boxer who fought his way out of the gutter only to lose the fight to bad company; American audiences of the Depression and World War II worked hard for their dollar. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, previously bored of the genre, relished Body and Soul for its accurate rendering of “a career which has seen him rise swiftly from the pool-rooms of the lower East Side and from the home of a poor but proud mother to the middleweight championship of the world, only to waste his dough…Mr. Garfield really acts like a fresh kid who thinks the whole world is an easy set-up—until the fates close inexorably in, until the wraps are ripped from his illusions and he finds himself owned, body and soul.”

Boxers, more than other characters, easily lose their souls to the golden calf, precisely because they have nothing to begin with. “You know crime don’t pay,” quips Rocky to Adrian’s pet store boss, but Rocky, like so many boxers, lives where crime pays better than work and breaks legs for Gazzo instead. Hollywood fixates on the Faustian boxer/mobster bargain up through the 1970s, contrasting the good way out of the projects with the bad way out. Charley Davis could’ve fought without the shady friends. Instead he loses, the same way On the Waterfront’s Terry Malloy earns a “one-way ticket to Palookaville” from playing along with his brother Charlie’s mob-backed dives.

Opposite, the boxer who resists crime can be a paragon. Rocky Graziano, played by Paul Newman in Somebody Up There Likes Me, starts as a hood and ends as champ. The closest Jim Braddock ever got to crime in Ron Howard’s Cinderella Man was scolding his son for committing one; Braddock would rather literally starve before a bout than filch a sausage.

There’s an American success ethic to the boxing film; gym sweat stinks just as sweet the sweat of labor, and the audience likes to see a man work for his bread when they have to work for their own. Even when there’s nothing to gain by the work, something about the boxer’s discipline ennobles even the talentless pugs stuck in their respective holes. John Huston’s Fat City stars Stacy Keach as washed-up journeyman Billy Tully, who divides his time in Stockton’s skid row between comeback attempts, alcoholism, scanty farm work, and floozies. Billy’s protégé, Jeff Bridges as Ernie Munger, is on the short circuit to the elder man’s fate, backstopped between bad promoters and bad trainers and a dead end life.

“Fat City,” wrote Roy Blount Jr. for Sports Illustrated, “is about more than boxing. Its characters represent an entire stratum of people — winos, gas-station attendants, onion-toppers, a “taciturn black upholsterer,” played by former welterweight champion Curtis Cokes — who have had more taken out of them than nasal bone and who are never going to make it to the sweet life symbolized in the title.”

Blount, like many viewers at the time, was struck by Fat City’s darkness but fascinated by the ability of the boxers to shine even in their hopelessness. It’s hard to get to the top, but we like watching the attempt, however fraught with failure and cheap wine.

The boxer has as little power as he has money. His problems reflect the zeitgeist of whatever makes people feel most helpless; fear of the Depression, of racism, of organized crime, of Communism, and of anything else the average Joe doesn’t have the means to resist on his own.

You can’t uppercut self-loathing or knock segregation’s teeth out. But you can externalize it and at least prove to yourself and the world that you have control over something. Life hasn’t broken the boxer; he’s just fighting something too big to hit.

Often, the boxer’s enemy is political, from Ali’s floating, stinging, and trash talking America towards civil rights to Rocky’s fighting Communism into extinction. On the Waterfront’s Terry Malloy cowed to the corruption around him, his boxing career meaningfully cut short by crooked union bosses and their mobster contacts. He didn’t step into the ring in On the Waterfront, but the memory of his failed career in the famous taxi scene gives Malloy the final push to speak out against Johnny Friendly’s union.

In Jim Sheridan’s The Boxer, Daniel Day-Lewis plays Danny Flynn, an ex-IRA soldier and boxer trapped by the Troubles’ sectarian violence and the 14 years of prison it earned him. Danny’s enemies are frighteningly real, IRA killers who don’t like their former accomplice’s rejection of the cause, but the hate and suspicion that blanket his world aren’t tangible. Boxing acts as an anchor to chain Danny into reality against a flesh and blood foe, at least one that won’t shoot him dead in a Belfast alley.

“When I get back in the ring,” Danny says, “you can’t imagine what a relief it is to feel the pain, to be back in the world again.”

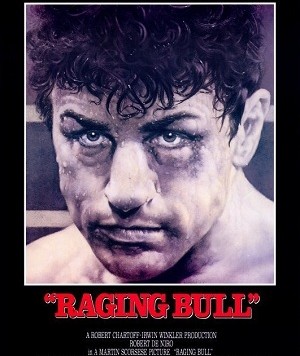

Sometimes the enemy lives inside instead of out. Films like Raging Bull and Fight Club battle inner turmoil by accepting and dishing out physical pain. Pathos means as much to the boxing film as poverty; a Puritanical kind of respect creeps into the film when the boxer suffers. Whether he earned the beating or not is irrelevant; pain is progress.

Fight Club’s benumbed narrator (Edward Norton) has a different, spiritual kind of poverty sprung from consumerism and a masculinity crisis, the twin vacuums of Generation X culture. He copes with his soullessness with an underground club where bareknuckle fights function like a bloody Mass. Stitches and a wired jaw might clash with his DKNY shirt, but to him it beats the cycle of cubicle, condo, and casket. “What does he need?” asks critic Omer Mozaffer. “He needs to feel.”

Raging Bull’s Jake LaMotta’s pain veers more to confession than Fight Club’s Mass. LaMotta, both as played by Robert DeNiro and in real life, had a mob of demons swirling around him, crippled by stupidity, sexual insecurity and jealousy he can’t even understand. If Fight Club’s narrator or Terry Malloy represent the issues of their time, Raging Bull looks at the eternal stranglehold violence and degradation have on weak men. He batters his wife and brother and the world in general, then drops his hands in the ring to soak up as much penance as possible. LaMotta’s supernatural ability to absorb punishment meant less about fortitude than self-loathing. “He hurt too much to allow the pain to stop,” wrote Ebert.

In the words of Middlebury College film studies professor Leger Grindon, “the foundation of film genres rests upon social problems shaped into dramatic conflicts.” The boxer lives beyond the lovable lug or the violent damned. In over 150 boxing films made from the medium’s beginning, the boxer guides us through society’s ugly bits, from the Depression’s debased poverty to man’s instinct for cruelty and need for redemption.

If we love the boxer for convention’s sake, as Scott suggests, gobbling the films like so much blandly pleasant Cream of Wheat, then we’ll have to cope with mediocrity for eons. The boxer is dug into film. Edison’s kinetoscope came alive with a boxing demo in 1891. Boxing films outnumber any other sports films and are the only sports films to take home Best Picture Oscars, in the case of Rocky. If the film shows a man without money, freedom, meaning, and self-respect, who throws a stiff jab, it’s hooked nearly every one of 7 billion humans because it offers something similar to hope. None of us have the money, freedom, meaning, and self-respect we want. The jab, though, looks easy enough to learn.